Origins of Khmer Classical Dance

Prior to 1970, Khmer Classical Dance, largely known as “court dance” was performed by a single troupe resident in the royal palace, “Royal Cambodian Ballet” or Lakhon Leung (king’s dancers) (Cravath 1). The Classical Dance has a long history associated with religious belief and monarchy, where inscriptions at temples recorded the presence of the dancers were dated back to as early as the seventh century (Shapiro-Phim 6). The repertoire of the classical dance consists of two types which are Roeung (dance-drama) which involves literary elements of plot, characterization, and dialogue, and Robam (pure dance) which is performed in the form of a sacred ritual (Lyons, 52). Documents from the seventh century A.D associated dancers with funeral rites and later dance was seen as a powerful offering to spirits in exchange for blessings (Cravath 181). Except for the story of Ram, which shares similarities with the Indian epic, music, gestures, and choreography of Khmer Classical Dance reveals distinct characteristics that only exist within the Cambodian worldview that Khmer dances embody (Cravath 179, 199).

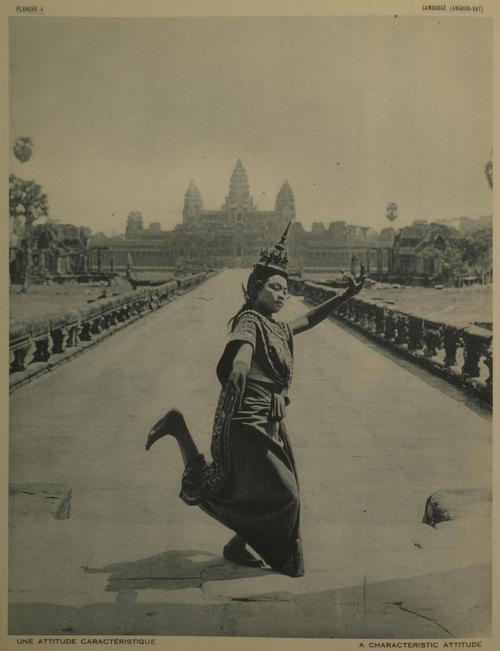

The idea that Classical Dance carries the essence of ritual and divinity remained unchanged until the French Colonization, where it became a symbol of the monarchy due to its link to the Angkorian civilization and its association started to shift from being purely for rituals to also being linked to pleasure, performance, profit, and politics (Cravath 528). During King Norodom’s reign in 1899, there were around five hundred dancers in the palace (Nut 48). The king after him, King Sisowath, still has almost a hundred dancers during his reign even with the increased pressure from the French (48). This shows how important classical dancers are in terms of representing the influence of the monarchy. During this period, classical dance was a representation of the royal family while starting to shift away from its ritual and spiritual aspect.

In the early centuries, performances of Robam as a ritual was believed to have the influence over monsoon rains and the land’s fertility, which therefore support the belief of kingship (Cravath 1). Power and legitimacy in the times of these ancient empires were displayed through conducting elaborative rituals where dance (and thus dancers) became a medium for royals to communicate with the divine and spirits (Shapiro-Phim 6). During the reign of King Jayavarman VII, one of the most powerful kings during the Angkor Era from 802-1432, installed around 3000 dancers in addition to dancers already in service in dedication to the spirit of his parents and for temple services throughout the kingdom (Cravath 184).

This does not necessarily mean that classical dances were no longer used in rituals and national ceremonies. During the funeral ceremony for King Sisowath in 1927 and King Monivong in 1941, dancers were arranged as escorts to attend the corpses of the kings during the funeral rites, while wearing white face makeup which is associated with the spirit world (Cravath 181). In addition, in the 1960s, Prince Sihanouk, who later became king and was named “The father of independence”, arranged for dancers to perform in a temple as a means to communicate with heavens in hope for rain, prosperity, and well-being, during one of his visits to Battambang province (Shapiro-Phim 187).

Until the exile of the royal family due to the Coup d’etat from 1970 to1975, classical dance remained the icon of Cambodian nationality despite the fact that its links to the monarchy were being severed (Tuchman-Rosta 528). Even after the destruction left by Khmer Rouge, Classical Dance was still referred to as the “soul” of the Khmer People, a symbol of connection to the past and to what it means to be “Khmer” (Shapiro 10).

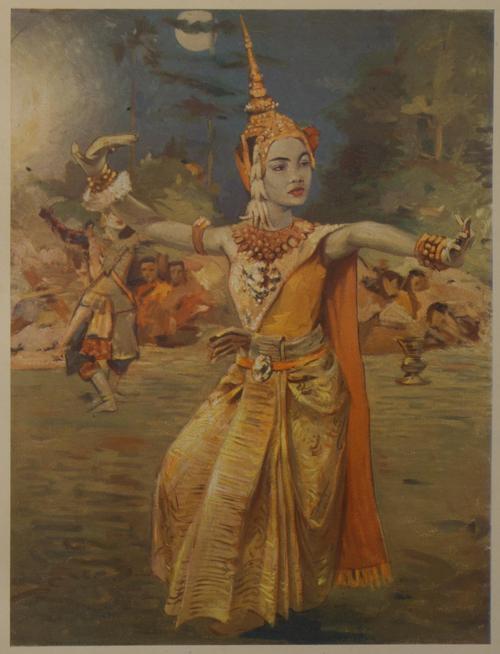

Performance of Tep Monorom Dance

Dancers of Khmer Classical Dance

In the early centuries of pre-Angkorean period, dancers were considered “slaves of the gods” and were given names such as “Gifted in the Art of Love,” or “Spring Jasmine” for their dedication in embodying the divine and spirits so that blessing and balance are given to all creation (Shapiro 48). The contrast is enlarged when comparing such names to names given to other slaves which are mostly “Cat,” “Dog,” or “Stinking,” (Cravath 183). During the Angkor era, dated from 802 to 1432, carved on the southern half of Angkor Wat’s east gallery were the myth of “Churning of the Sea” which featured celestial dancers known as apsaras (Cravath, 185). Thus, Apsaras came to symbolize not only the welfare of the kingdom and power of monarchy but also the center of Angkorean cosmology with its embodiment of Khmer’s life-creating myth ( Cravath 185). In the case of Buong Suong, dancers performed the role of supernatural forces such as celestial deities, which in a way can be interpreted that the dancers thus became the deities themselves with the responsibility of both the giver and the receiver (Cravath 197). Even after the demise of the Cambodian monarchy in 1970, palace-trained classical dancers were still revered as a powerful symbol of Khmer identity (199). Prior to the Khmer Rouge regime in 1975, the classical dancers in the capital city of Phnom Penh took on an integral role in not only rituals but also in national celebrations for dignitaries, tourists, and the local population (Shapiro-Phim 180).