Anti-Semitism in the Press

In order to discern the treatment of Jews as an ethnic minority in interwar Poland, it is important that we examine explicit appearances of anti-semitism. The press presents an effective way to disseminate ideology. Ideals presented in the press reveal a relatively large number of individuals that share said ideals, for there are sufficient sentiments for the production of and an audience for a particular ideology. The existence of anti-semitic ideology in the press during interwar Poland is therefore evidence of a significant number of Poles that shared anti-semitic sentiments.

In order to discern the extent to which anti-semitism was widespread and impacted the treatment of Jews in interwar Poland, it is helpful to briefly summarize the political landscape. The ideological roots of anti-semitism rested within the rightist National Democratic Party (NDP) or Endecja, one of four major political parties in interwar Poland (Dobrowolska 3). The Polish Socialist Party (PPS) or Sanacja, presented the biggest threat to the NDP, “which pushed for a multiethnic model of Poland and expressed more sympathy for minorities, including Jews,” (Dobrowolska 3). The remaining political parties consisted of The Peasant Movement (PSL), which advocated for the interests of Poland's large farming population, and the right-leaning Christian Democrats, or Chadecja, which sought to develop Polish society according to Catholic value (Dobrowolska 3). This political distribution reveals that two of the four major Polish political parties during the interwar period were right leaning or Catholic focussed, which fosters the exclusion of Jews as ethnic minorities. While it is true that the images presented below represent a right wing perspective, and do not represent the views of all Poles during the interwar period, the frequent dissemination of anti-semitic images of this nature was effective in normalizing anti-semitism and directing anger with economic situations toward Polish Jews.

This 1937 political cartoon, which appeared in the right wing news paper called Pod Pręgierz, reveals a sentiment among a portion of Polish citizens that blamed Jews in Poland for economic stagnation. Bold text on top reads “Recepta na kryzys,” which translates to “A recipe for crisis,” presumably referring to the occupants of the cart. The cart is filled with Jewish caricatures, illustrated with predominantly large noses. Most of the caricatures are smiling, indicating that they are either blissfully unaware or immune to human emotions like fear. This serves to dehumanize members of the Jewish community. This dehumanization is further realized with the packed nature of the cart. It is dark inside, symbolizing evil, and there seems to be no room to sit down. The sections of the cart resemble cages rather than seats which is likely an attempt to get an audience to associate Jews with animals rather than humans. One caricature at the end of the cart seems to be aware, shocked, and horrified with his situation, yet none of the others seem to heed his warning. The fact that only men occupy the cart seems significant, for even an anti-semetic audience likely would not want to see women and children treated badly. The inclusion of women and children would have potentially garnered sympathetic pathos which would have been unproductive to the anti-semetic message.

The target audience is obviously the right wing anti-semetic Polish public, but probably also includes more moderate Polish citizens. The text underneath the image reads “Ten eksport wzmocniłby na pewno nasz bilans handlowy!” which translates to “These exports would definitely strengthen our trade balance!” This puts an emphasis on the economic cost for Poland to contain Jews. It was a right wing narrative that Poles had to defend themselves against the economic domination of Jews. The text here is meant to culminate anger toward Jews for any individual economic hardship. The image implies that if all the Jews were to be expelled, the financial situation for Poles would be improved.

The scary thing about this image is that it is not far off from what actually ends up happening to Jews in Poland just a couple of years later. In fact, the cart and railway depicted here looks eerily similar to the ones that transported Jews into ghettos and extermination camps during the Holocaust. This leads me to wonder if drawings like these could have helped inspire some of the actual methods used in the Holocaust.

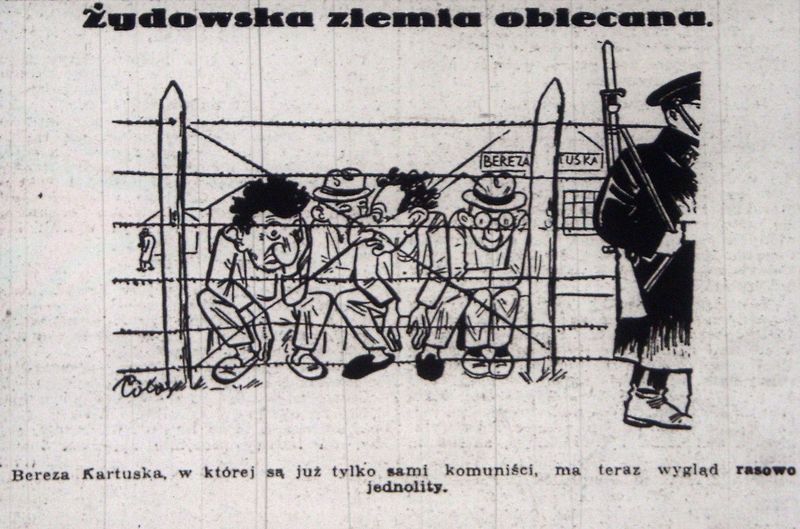

This 1936 political cartoon displays overt anti-semitism in the right wing press. We once again see the Jewish caricature with big noses and unattractive features. The Jews appear behind a fence that is guarded by what is presumably an armed Polish authority. The slouched posture of the Jews connotes weakness in comparison to the upright dignified position of the Polish figure. Text appears in bold letters that reads “Żydowska ziemia obiecana” which translates to “Jewish Promised Land.” This implies that Jews in Poland are destined to be incarcerated. The building in the background is labelled as Bereza Kartuska which was a Polish prison that became operational in 1934. This has significant implications because it leads us to infer that the cartoonist thinks the Polish government should sponsor the incarceration of Jews. The text underneath the image reads “Bereza Kartuska w której są już tylko sami komuniści, ma teraz wygląda rasowo jednolity,” translating to “Bereza Kartuska in which only the communists are now, looks racially uniform.” This implies that the prison mostly contained communist prisoners and directly associates Jews with communists.

Negative sentiments toward communists came from the era of partition in which Russia (while not communist at the time) was the first to seize control of Polish territory. In 1920 the Bolsheviks attempted another invasion, garnering resentment toward Russia and communism. The right wing presented a narrative during the interwar period, particularly during the 1930s, that labelled Jews as the fourth partitioner that Poland was never able to get rid of. Papers like Pod Pręgierz promoted conspiracy theories of Jews plotting with communists to undermine Polish nationality. British historiean Peter Stachura points out that during the interwar period "there was, as a corollary, a widespread perception among Poles that many Jews, especially those in the Eastern Provinces, welcomed and in some cases actively supported the advance of the Bolsheviks into Poland in 1920," (Stachura 85). This cartoon is supposed to encourage people to share the sentiment that Jews should be locked up before they get the chance to collaberate with communists to dismantle Polish nationality.

This image reveals exclusion of Jews from Polish identity quite literally. Once again we are presented with imagery that is scary because of its future actual implementation. The fence pictured here looks very similar to the fences that would come to surround concentration camps a few years later. The barbed wire makes it dangerous to try to escape, but enables the prison to remain visible from the outside. This is dehumanizing for the Jewish prisoners, who are able to be looked upon like animals in a zoo. Like the previous image, this one also excludes any women or children. The cartoonist only wants the audience to associate Jews with men. The right wing press did not want people to consider that Jews could also be women or children, for they should not be connoted with innocence of any kind.

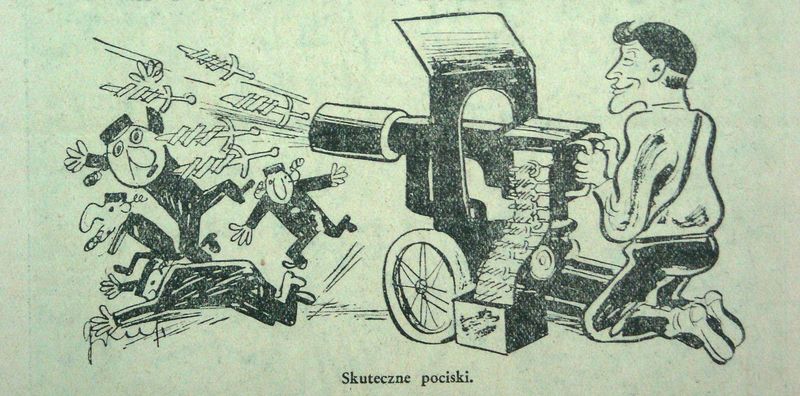

This 1935 right wing political cartoon depicts a young Polish nationalist shooting and presumably killing Jews. The swords coming out of the machine are Chrobry swords, a symbol for Polish nationalism. The swords were used to crown Polish monarchs before the partitionist era but have since become a symbol of hate and facism because of the meanings it took on during the interwar period. The sword illustrates a nationalist sentiment that quite clearly cannot include Jews and in fact is cultivated from the killing of Jews. The text reads “Skuteczne pociski.” which translates to “Effective missiles.” The period at the end of the fragment suggests a finality that implies Jews are to be killed which would be effective for the Polish state.

We once again see the Jewish caricature who is further dehumanized. They are depicted with large noses and ears that resemble animals more than people. The features of the young Polish man’s body are clearly defined, while the bodies of the Jewish men are depicted as abstract shapes. This more clearly depicts animalistic imagery, as the caricatures are tilted into positions that resemble pigs. This is significant not only because it dehumanizes Jews, but also because of the implications of a pig in particular. Pigs are associated with terms like fat and greedy, implicitly referring to the supposed Jewish economic domination. Furthermore, Jews do not eat pigs because they are not kosher, so to present that imagery is particularly offensive.

The images presented here reveal a clear anti-semitic trend in right wing press in Poland in the 1930s. Stachura emphasizes the “political pressures, articulated most vociferously, but by no means exclusively, by the Endecja [NDP], to construct a strong country in which the non-Polish minorities should not be allowed to constitute an impediment to the realisation of this goal. Dmowski's prescription of an integral Polish-Catholic nationalism was designed to form the basis of a unitary state,” (Stachura 79). Right wing members of Polish society used the press to culminate fears of economic and political domination by Jews. They used traditional enemies like the Soviets to cultivate traitorous ties with Polish Jews. That is not to say that all Poles shared these sentiments, as is revealed by the presents of the PPS and their advocacy for a multi-ethnic Polish future. While the presise extent of anti-semitic treatment of Polish Jews during the interwar period is difficult to assess, it is clear that there was a valient effort to motivate it.