Posters and Magazine Clippings

Posters and Magazines provide cultural insight into any society because they are often implemented for advertising and leisure. Unlike newspapers and textbooks, posters and magazines are not necessary to obtain any valuable information. Ordinary members of society voluntarily seek out or choose to pay attention to this medium.

These posters and magazine clippings are also significant because of their purpose. Most of the images below aim to advertise a particular event, institution, or idea. Marketers utilize both subliminal and overt techniques to influence the minds of consumers. Because of these techniques, there exists a clear correlation between societal norms and advertising. While this correlation is useful, it does not mean that advertisements can be used as accurate historical records. “Fundamentally, advertising seeks to shape,” and this ultimate aim cannot be ignored (Parkin 5). Rather than clear historical documentation, advertisements “can only reveal the ideologies and messages that advertisers hoped would sell products,” (Parkin 5). The idea that marketers sell ideas along with their products means that advertisements give us a unique lens into societal norms. These societal norms give us insight into the elements that defined Polish identity and culture.

This 1934 magazine cover portrays the emphasis on education that was an integral part of Polish identity during the interwar period. The magazine clipping aims to advertise the ideal of teaching. The shading that takes up most of the background accentuates the cloud of smoke emanating from the torch which draws the eye to the only meaningful text “Sprawy Nauczycielske” which translates to “Teaching Matters.” The shading draws focus to the head of the torch. Fire is biblically representative of hope, eternity, passion, and most significantly rebirth and resurrection. The interwar period in Poland marked a valiant effort “to rejuvenate the schools and universities following the manifold constraints of the partitionist era,” (101). Education had always been an important part of Polish values and became doubly vital to the successful rebirth of Poland as a state. The imagery presented here is a biblical resurrection of the vitality of teaching. After a long period of absence teaching provided a way to solidify and preserve Polish identity. The smoke is symbolic of the eternal flame that lives on in the Polish youth. Education provided young Poles opportunities for success and a successful generation would mean the maintenance of Polish statehood and nationality.

ZNP is a reference to the school district of Vilinius that distributed the magazines. Magazines of this nature were distributed monthly, revealing the persistent emphasis on the importance of education in Polish society.

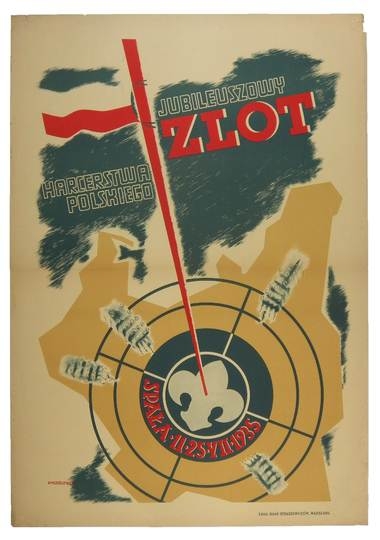

This 1935 poster explicitly ties Polish nationalism to Christianity. There is a chaotic aesthetic of shapes and colors that makes it initially hard for an audience to focus. The red however, ultimately draws the eye to what seems to be an outline of the fleur de lis, a Catholic symbol often associated with purity. The flower seems to be used as a symbol for the Polish Scouting and Guiding Association, which was established in 1918 and continues to this day. The Polish Scouts reinforce education as an important aspect of Polish culture as well as the idea of purity as associated with Polish youth. The flower has a calming effect in the midst of the chaos. The flower is also depicted in the center of a bullseye which is illustrated on top of a map of Poland which implies that Poland is succeeding. The “dart” that represents success is the Polish flag. This connotes a strong sense of nationalism and implies that the path to success for Poland lies on a Polish identity (represented by the flag) that is directly dependent on Catholicism (represented by the fleur de lis). The poster is from 1935, which was almost 20 years after the establishment of Polish statehood. By this time, Polish identity and creativity was flourishing. The imagery here suggests that nationalist Catholicism has provided and will continue to provide success.

The blue color serves to draw an audience’s attention after seeing the flag and bullseye imagery. The different color emphasizes the words on the poster which translate to “Polish Scouts” and“Jubilee Rally.” The Polish Scouts as an organization reinforces the nationalist theme, for it promotes Polish pride and future leadership. The poster also draws on the importance of education as it points to Polish youth as the future leaders and preservers of Polish identity. The poster is an advertisement for a celebration rally for the national organization. This reveals the celebration of Polish identity as hopeful for the future.

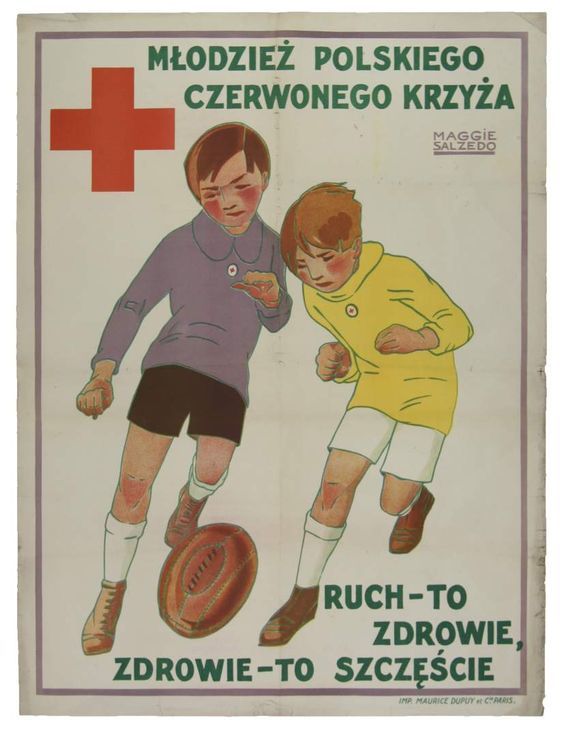

This poster is an advertisement encouraging Polish youth to join the red cross. Once again, the poster emphasizes education and a focus on the development of Polish youth as an integral part of Polish identity. The boys are playing football which is Poland’s national sport. This subtly perpetuates nationalism, implying that the boys enjoy the national sport and are proud to be Polish. The illustration of the sport is also likely strategic, as it suggests that the boys are ordinary kids which subsequently implies that ordinary boys can and should join the red cross. Advertisements like these likely encouraged the productive development as youth to carry on Polish identity. The white background to contrast the red cross subliminally connotes the colors of the Polish flag, reinforcing nationalist sentiments.

The fact that only boys, not girls, are present in the poster is significant. There seems to be a portrayal of nationalism as a masculine ideal in order to imply strength. Football is also a gendered, masculine sport, suggesting that to be Polish is to be manly and therefore strong. The text appears in green, a color often representing growth and life. The text translates to “Polish Red Cross” and “Move it, Health, Happiness.” The text aims to affiliate Polish identity with growth and vitality as well as to motivate productive youth. The designation of youth as a target audience connects health and happiness with the preservation of Polish culture.

A commitment to education was a defining element of Polish identity during the interwar period. Not only is the desire to reach and educate Polish youth clearly reflected in these posters and magazine clippings, but it also had far reaching, tangible impacts throughout Poland. The mayor of a rural Polish village in 1925 reflected on the rapid educational advancements implemented: “how much our schools have advanced, as indeed in the whole of Poland, can be seen when one compares them with what they were half a century ago,” (Słomka 270). It seems as though an emphasis on education was a uniting component of Polishness that bridged rural regions and cities alike. All of these images illustrate an explicit focus on youth and education, substantiating its prominent role in Polish life. Simultaneous strong associations between Polish identity and Catholic values meant that catholicism was often intertwined with education. Thus, while the patient role education played in Polish identity presented an opportunity for Polish youth to perpetuate Polish nationality, the affiliation with catholicism presented an obstacle for ethnic minorities like Polish Jews to be part of said national identity.