1920s and 30s: From a Sandwich Shop to the American Dream

As Judaic Studies expert Ted Merwin stated, “the history of the delicatessen is the history of Jews eating themselves into Americans,” (Merwin 1). The development of Jewish Delicatessens in NYC in the 1920s and 30s created a new Jewish American identity that both contributed to and was influenced by New York City mainstream culture. The economic success that delis afforded the Jewish community enabled them to participate in mainstream activities that caused widespread assimilation among the Jewish community in NYC. However, the persistence of Jewish delis throughout both decades morphed Jewish identity into something that could thrive in American society.

If immigrants pioneered the existence of deli’s as a communal space, it was their children who reinvented them into a secular space that became quintessentially New York. Throughout the interwar period, second generation Jewish Americans made the NYC deli a place that combined Jewish style food and atmosphere with mainstream elements of flare and fame. The Jewish deli became a place of vastly diverse consumers in religion and social status by associating with the rise of Jews in entertainment. The deli provided a flashy atmosphere with various options for NYC’s actors and stars as well as those down on their luck (Merwin 56).

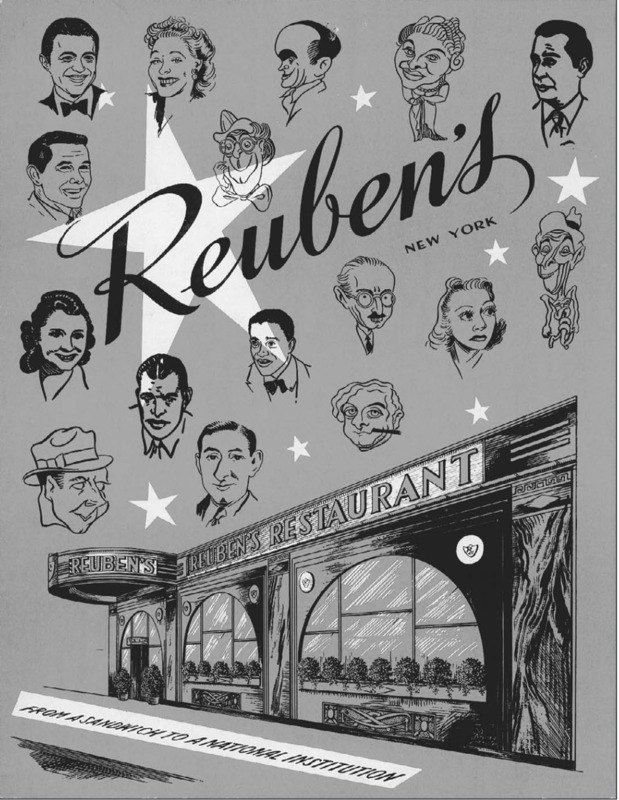

This image is a menu cover from a delicatessen called Rueben’s located in New York City from the 1920s. The image features caricatures of famous American actors from the 1920s, associating the deli with importance and fame. This is an explicit reference to the large presence among NYC Jews in the “showbiz” culture of the 1920s. In fact, throughout the decade Jews “provided the lion’s share of the creative talent, financial backing, and real estate for the entertainment business,” (Merwin 59). Owners of Jewish delis took elements from this popular culture and expressed them both inside and outside the restaurants, transforming a typical sandwich into a modern, fancy meal. Complementing these caricatures’ representation of fame, is the drawing of the institution itself, which presents with modern architecture and a big flashy sign, perhaps representative of Rueben’s real neon flashing sign that stood outside the actual restaurant. The flashing lights would join the lights across hundreds of buildings in Manhattan, providing a physical representation of the deli’s assimilation into NYC culture. The celebrities and flashy signs associate both the deli (and by association the American Jewish owners) and potential patrons with what NYC exuded: prosperity and modernity.

This image also presents themes of regional and national pride, advertising “New York” right under the larger font of “Reuben’s,” explicitly connoting the deli with what is a culture of New York City. The choice of Jewish deli owners to feature a blatantly Jewish last name like “Reuben’s” was perhaps risky, for Jews were still discriminated as uncivilized, but the preservation of Jewish names indicated that Jews had attained the American Dream. Print underneath the restaurant clearly reads “From a Sandwich to a National Institution,” revealing Rueben’s desire to associate itself with American ideals. This claim that Jewish life has become “institutionalized” implies that Jews and their culture were becoming part of American society. However, the lack of emphasis on kosher food and hebrew writing in this image suggests a careful balance between religious and secular Jewish culture. Delis like Rueben’s therefore created a new Jewish identity that was secular enough to be institutionalized into NYC culture. This shift from the more religious elements in the 1910s was influenced by the fast, vibrant culture of NYC itself.

This is a photograph of the employees of Katz’ delicatessen standing outside of the institution from the 1930s. The photograph depicts eight employees, all but one of them male and a New York City police officer. The authority figure of the police officers implies public support and desire to protect the presence of the deli. The inclusion of the police officer as a non-explicitly Jewish patron of the facility indicates a greater immersion of the deli into NYC daily life and culture. The name of the restaurant is presented in neon, flashy lights in sleek windows in both English and Hebrew. This provides evidence of a desire to stay connected to a lingual community and simultaneously appeal to a more modern New York City clientele. The more modern elements make the deli appear more kosher style, rather than strictly kosher. These kosher style restaurants are what moved Jews into mainstream NYC by fueling second generation immigrants desire to achieve the American Dream (Merwin 3). The connection to NYC showbiz culture is clear in this image with a sign above the windows that reads “We are Famous for the Best Sandwich in Town,” associating the restaurant with fame and high quality. The diction of the phrase “in town” suggests that the owners seek to contribute to a local cuisine and community. Implying the food is well known is indicative of a desire of the Jewish American owners to be part of this local culture. The 1930s is when a deli becomes an emblem of something that is quintessentially New York. This association is powerful and reveals a significant assimilation of the Jewish culture into the New York mainstream.

The image features the employees of Katz delis who are almost exclusively male and uniformly well dressed in suits and ties. The choice of the white colored tops and aprons gives the Jewish community an opportunity to present themselves as pure and clean in a time where economic depression might lead people in a more unsanitary direction. The male to female ratio of employees is particularly interesting because Jewish women were the ones primarily involved in food production in the home. However, the popularity of Jewish delis reinforced original ideals of masculinity because of the emphasis on meat and showbiz. The maintenance of Jewish delis as a more male dominated space represents how gender was represented in an evolving Jewish identity. Even as Jewish culture began to shift from a more religious to secular forms of expression, it was commonplace for males to be dominating spaces outside of the home.

We once again see a balance between explicitly Jewish elements and mainstream culture. Like Rueben’s, Katz’ deli displays a very Jewish name in the window, though it appears below the association between their sandwich and fame. Having their name appear in lights references how class was changing within Jewish American identity. Jews were able to afford flashy lights and appear as a more modern, upscale place to dine and they could offer this message to their consumers. However, delis like Rueben’s and Katz’ were able to appeal to a wide range of social classes throughout the interwar era. Their association with the entertainment industry meant that it was a place for successful entertainers as well as ordinary and working class individuals. In other words, they could offer higher class consumers a depiction of what they were, and lower class consumers a picture of what they could be (Merwin 62). The customers would be consuming not only a sandwich, but also the NYC and American prosperity, the same elements that began to comprise Jewish American identity.

This is a photograph of the interior of Rialto’s Restaurant and Delicatessen from the 1930s. This gives insight into the interior of a Jewish deli in NYC. The shelves are very organized and offer a large variety of products. During an economic depression, being able to serve a large volume and variety is very significant and could tell me a lot about the economic success of Jewish delis in the 20th century. The endless options made customers of Jewish delis feel important and added to the associations between Jews and prosper. However, this image of the interior is more revealing of how the delis actually operated. While the exteriors were adorned with flashy signs and sleek glass windows, the interior appears rather basic. This could be applied metaphorically to Jewish identity of this time period: appearing upscale and flashy but having feelings that were more traditional and similar to their ethnic roots.

Once again we see an exclusively male staff including the chef and waiter, revealing that Rialto’s food production and service was provided by exclusively males. The perpetuation of Jewish delis as a masculine space can be attributed to the close connection with the entertainment industry, for Jewish delis “took on a highly theatrical vibe of their own,” (Merwin 68). The waiter’s attitude at the Jewish deli became an essential part of the experience. Deli waiters were often former actors from the Yiddish stage and played “stereotypically snooty” Jewish tropes in order to entertain customers (Merwin 68). Thus, the waiters were often intentionally obnoxious and bossy, qualities that while entertaining coming from a male waiter, might not have been so widely accepted from a woman. Additionally, customers accepted and even enjoyed a sarcastic waiter because of the familial closeness that comes with those types of remarks. If coming from a woman, the remarks could be sexualized rather than taken in jest.

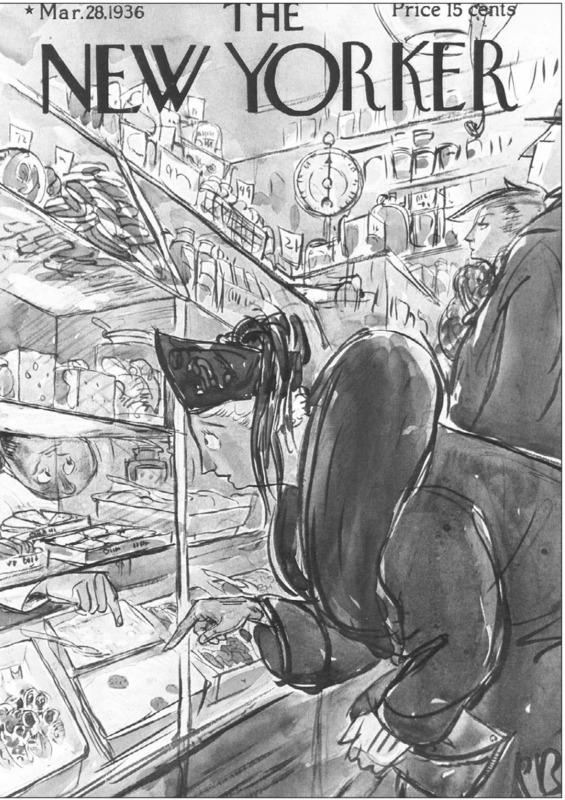

This is a cover from a March 28th New Yorker magazine from 1936. The origin of this source -- a popular New York magazine publication -- demonstrates an acceptance of a general New York audience of Jewish delis as part of New York and American culture. Even in the thick of the Great Depression, this image illustrates the Jews’ ability to feed themselves and their families.

The cover illustrates what is the ideal Jewish woman tediously selecting food products from a Jewish deli’s large display case. The appearance of the woman is significant, as it differs from previous images. Rather than a notably slim, sexualized figure, the woman has a thicker built with softer edges and facial features. As the 1930s was characterized by an economic depression, the thicker build is likely a symbol of the Jewish woman’s wealth and ability to feed herself and her family. The woman here is clearly presented as a more maternal figure. This depiction indicates the shift in gender roles in Jewish American identity.

While Jewish American immigrant women were expected to cook for their families, the second generation immigrant could afford to take out meals. With extra time, some Jewish women began to join the workforce and bring in extra money which contributed to the economic rise of the Jewish community (Merwin 72). However, even as the role of the Jewish wife and mother changed, their status as inferior to men remained stagnant. This could be explained by a larger phenomena in the United States as a whole. In her book Food is Love: Advertising and Gender, food historian Katherine Parkin argues that the thematic trends in food advertising remained markedly the same throughout the 20th century in spite of constant societal change (Parkin 1). These themes focussed on the American woman’s responsibility as homemakers to show love for their husbands and children. Parkin points out that “the ideology that identified women as homemakers and men as breadwinners held strong, even as reality strained this ideal,” (Parkin 1). So even as assimilation into American culture changed the role women played in the Jewish community, the American culture in which Jews assimilated to maintain the traditional gender roles of men and women. This stagnant representation is further emphasized by the presence of the male service worker in the deli depicted here. The trend labelling the deli as a male workforce remains consistent.