1910s: From Religion to Community

Judaism almost always evolved around meat, as is evidenced by the existence of ceremonies such as Shelamin’s (full), where Hebrews eat meat sacrificed by a priest as an expiation of sin, existence for over 2,000 years (Merwin 4). It was in fact, according to the Jewish religion, a rabbi who invented the first sandwich to commemorate the enslavement of Jews by the Pharaohs of Egypt in what he called korech (to encircle or envelope) (Merwin 5). The emergence of the first delis in New York City in the early 20th century was therefore not unique in its emphasis on salty meats. What was unique was the deli’s social, along with the cultural and religious atmosphere that gave Jewish immigrants a place to congregate outside of the synagogue.

While the first delis appeared in NYC in the early years of the 1900s following a wave of Jewish immigration from Eastern Europe, this was not when their use became commonplace. The typical newly arriving Jewish immigrants could not afford smoked and pickled meats that delicatessens offered and Jewish women, who were expected to spend all day preparing family dinners, were insulted by the deli’s alternative (Merwin 7).

Why then, did Jewish delic maintain a presence, albeit minor, in the first decade of the 20th century? The answer to this question could be found in a common tendency among most minority groups, particularly in American cities to identify physical social spaces. Sociologist Ray Olden coined the term “third place” to describe this place that held social interactions between the realms of work and home (Merwin 8). The first Jewish delis were established by and catered to Jewish male immigrants that lacked a wives to make them food. This explains the emphasis that Jewish delis maintained around red meat as a more masculine taste.

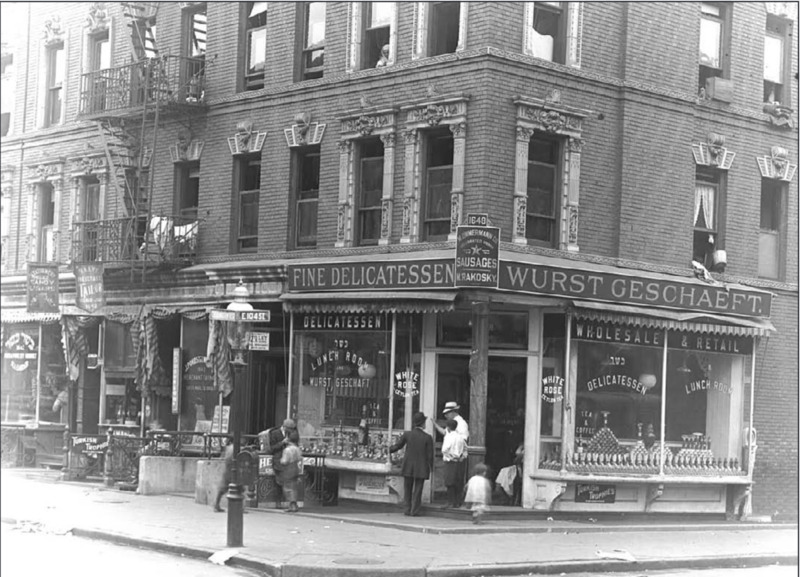

This image is a photograph from a kosher delicatessen in East Harlem taken in 1911 provides a starting point for Jewish American culture in early 20th century NYC. The fact that the deli is clearly kosher and exhibits hebrew writing, is evidence of ethnic and religious continuity. The hebrew writing on the window, allows Jewish Americans to easily identify the establishment as a Jewish space and remain connected among a common language and presents a place for this connection to take place. The photo pictures two Jewish men (as is indicated by the hats they are wearing, which are common among the Hasidic community) as well as a boy and a much younger girl. The two children are presumably related to one or both of the men. The individuals here appear to be consumers visiting the deli to purchase food. While the young girl is moving and off to the side, the boy appears to be preoccupied in conversation with one of the older men. This is significant because it reveals a male gendered interest in Jewish delis. The consumers of delis being men is consistent with Jewish delis emerging as a “third place” for Jewish men in their early years. A social conversation surrounded by red meat, was perhaps advertised as a more masculine activity.

The exterior of the restaurant is very basic. The facility lacks flashy signs and lights, and seemingly blends into the street among the other buildings. This implies that the owners of the restaurant either did not have or did not aim to show off a particular large amount of economic success. While clear elements of Jewish culture adorn the windows of the deli, there are not any explicit references to New York City or its culture.

Therefore, this image implies a desire among early 20th century Jewish Americans to remain connected to their ethnic roots and provide a sense of community with each other, rather than a desire to assimilate into an American or New York cultural mainstream. While the deli elevated the status of Jewish meat from a religious element to a social symbol of community in its early years, its presence remained relatively inconspicuous to those that were not Jewish men. Nonetheless, in the early 1900s, the NYC delicatessen became the first public Jewish foodway in the United States. This foodway emerged as the general American perception of Jewish immigrants was uncivilized (Merwin 12). The basic structure evident above is there for an interesting and significant choice among the first creators of Jewish delis, as the establishments perpetuated these stereotypes to some extent by providing a space for eating with hands, loud conversations, and talking with full mouths of red meat. The persistence of these elements among Jewish men in spite of negative connotations reveals an apathy toward what the mainstream population might think and a stronger emphasis on cultural roots. The first delis provided a place where Jews of different origins, social classes, and levels of religiosity could forge a common community.