Late 20th Century Advertisements: Post Peronist Era

About halfway through the twentieth century, Argentina underwent a political and economic transformation with the election of Juan Domingo Perón. Perón implemented reforms that introduced purchasing power to the working class. This power turned into “the epitome of national progress and social equality” (Milanesio 21). Perón sought to use the working class as an instrument to grow Argentina’s internal market while making sure workers benefited. Thus, members of the working class became a major focus for state policy. For the first time, the lower socioeconomic sector of Argentina became mass industrial consumers. Simultaneously, organizations emerged to promote national advertising in a post-World War II economy. The result was an expanded industry and a shift in advertising techniques. An expansive mass consumer culture emerged in Argentina and challenged advertisers to engage a working class audience. A change in audience meant a change in advertising themes and techniques. Marketers shifted away from modernity and comfort and focused instead on economy and national identity. These themes are reflected in yerba mate advertisements created after the Peronist era.

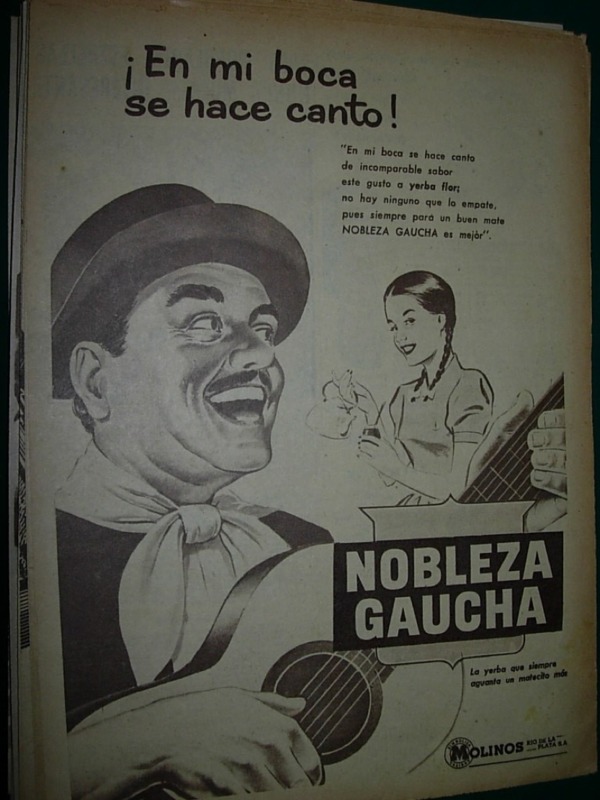

This Nobleza Gaucha advertisement for yerba mate from the 1960s reveals the shift from foreign formulas to national advertising. The dominant yerba mate brands on the market shifted mid-twentieth. This coincided with the shift in the demographic that was able to participate in mass consumerism. During the Peronist era, advertisement rhetoric shifted away from elitist language and focused instead on inclusion. The names and slogans of brands in a variety of industries changed to include all Argentinians (Milanesio 75). During this same period, Nobleza Gaucha became a prominent brand for yerba mate. The name itself conveys an Argentine national identity, emphasizing gaucho culture. gauchos are skilled horse riders known for their distinctive costumes. Permeating strength, gauchos became and persist as a national symbol in Argentina (Carolina). Perón emphasized Argentine nationalism and declared Pato – a sport in which gauchos are featured – the official national sport in 1953. Milanesio contends that in this period, “working-class consumers influenced the language, the visuals, and the mediums of advertisement,” (Milanesio 73). She cites a shift from the “longer, elaborate, and more argumentative,” nature of early twentieth century advertisement to “a new simple formula” that “favored short arguments and catchy, sometimes infantile rhymes and slogans,” (Milanesio 73). The advertisement here exhibits these shifts. In contrast to the big blocks of text provided with early twentieth century advertisements, this advertisement presents a catchy slogan “En mi boca se hace canto!” – which translates to “In my mouth there is a song!” – and a simple quote describing the superior flavor and quality of the mate. Milanesio also points to a more conversational, casual style that advertisements embodied to appeal to a working class audience. In this advertisement, the dress of the man and the woman is very casual. The man is dressed in traditional gaucho clothes, and the woman adorns a casual rural dress. The gaucho dress along with the guitar represents Argentine national identity. The development of distinct national advertising is also clear with a slogan that is informed by Argentine culture and the presence of the inverted exclamation mark. This juxtaposes the earlier advertisements that were somewhat grammatically flawed and uninformed by national culture.

This advertisement also displays a slight shift in gender stereotypes that were portrayed in advertisements after the Peronist era. In contrast to the direct feminization of mate, the beverage started being displayed around traditional gaucho culture. Here a casual, but masculine man is essentially advertising the drink. The gender stereotypes follow the traditional theme, as the woman is portrayed preparing the drink for the man. Both individuals are smiling, indicating that they are both happy with these roles that mate is reinforcing. The pigtail braids with bows and simple dress is a repetitive trope among mate advertisements from this period and are typical of a working class rural attire. The people featured in this image are therefore relatable to working class consumers.

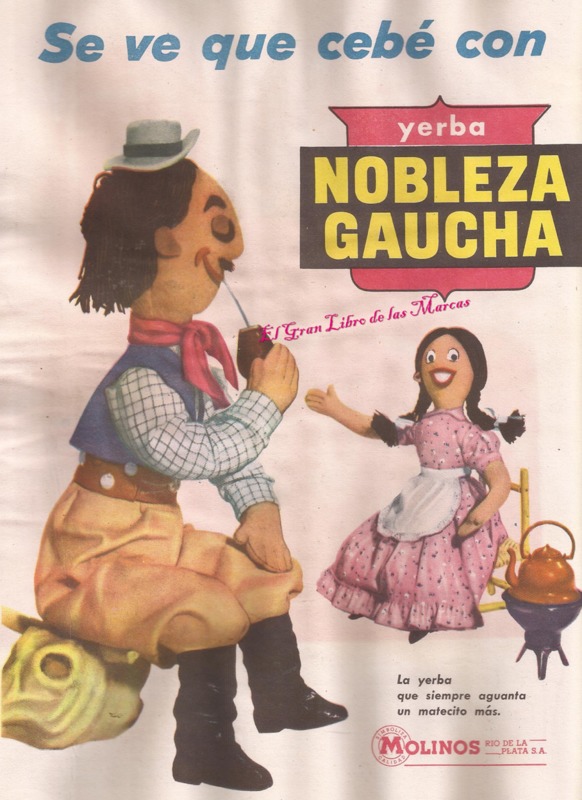

Similar in style, this Nobleza Gaucha advertisement from the 1960s depicts similar themes. There is a short line of large text at the top of the advertisement that reads “Se ve cebé con,” which translates to “It looks like I fed him with.” This emphasizes traditional gender roles in that it is the woman’s job to provide nourishment to her husband. The female doll sits smiling with the tools to prepare the mate, while the male doll sits relaxed drinking the mate. Unlike the advertisements from the early twentieth century, the woman does not take part in drinking the mate. Instead, she remains relatively far away from her husband as he enjoys the beverage. Rather than feminizing the mate, this gives it a strong, masculine appeal. In this image, the woman is also wearing an apron, implying that she has been preparing food. In both Nobleza Gaucha advertisements, the couple is depicted as very happy with these roles. Milanesio asserts that some Argentinian advertisers used “supposed insecurities and inexperience” of young women in the married lifestyle (Milanesio 141). By implying that this mate will make a husband happy, this advertisement is selling an easy way to be an ideal wife. While the Peronist era marked an important shift toward inclusion in a consumer market, it also promoted the woman’s role in a domestic sphere (Milanesio 147). Perón asserted that the woman’s most important role was at home, so while many products were marketed toward women, advertisements emphasized the benefits said product could bring to the domestic female role (Milanesio 147). This advertisement is selling a way for women to benefit this role.

Along with traditional gender roles, this advertisement conveys themes of national identity and durability. The male doll featured in the image is dressed in clear gaucho attire. He is wearing the sombrero surero (traditional gaucho hat), red scarf, bombachas (trousers), belt, and boots (Carolina). The gaucho is a symbol of strength and national pride, and this advertisement is using this to its advantage. It is conveying that consumers could be proud Argentinians if they purchased Nobleza Gaucha mate. The man is sitting on a hard stump, rather than an actual chair, accentuating the strength of the gaucho. This shows a shift away from the comfort that was displayed in the early twentieth century advertisements. Instead, this advertisement promotes the durability of its mate with text that translates to “The yerba that always endures a little more mate.” This could mean that the mate from Nobleza Gaucha lasts longer than other brands, appealing to the economy of working class Argentinians.

Both of these advertisements convey evidence of attempts to appeal to a working class audience. The shift from the early twentieth century style -- going from big blocks of text to short slogans, and creating a casual tone -- the development of more inclusive brand names, and the introduction of purchasing power to lower socioeconomic sectors of Argentinian society support this theory. With this shift, came a new way of portraying gender roles in the advertisements. The women in both of these images are portrayed as an ideal wife, preparing mate for her masculine husband. Advertisers used these images to appeal to the insecurities of young women entering married life for the first time, reinforcing unevolved traditional gender expectations.