The Climactic Chanoyu: Sen no Rikyū’s Ceremony

After monks Eison and Eisai, there were numerous other Zen Buddhist monks--notably the tea masters Jukō and Jōō--that contributed to the tea ceremonies of Japan and continued to solidify the connection between Zen and tea, but the most famous was the grand master of tea Sen no Rikyū (Driem). Known for his development of the tea ceremony chanoyu, Sen no Rikyū transformed the practice of tea into a spiritual practice of “simplicity and sincerity” (Hohenegger). Implementing his practices of Zen Buddhism, what had become an elaborate practice of sharing tea in the ruling class of Japan was transformed into a spiritually enriching experience.

Born into a wealthy merchant family, Rikyū was a gifted and self-confident pupil who studied Zen and tea from a young age under master Takeno Jōō (1502-1555 CE) and was chosen quickly as a tea master by Oda Nobunaga (1534-1582 CE) (Bodart). After Nobunaga’s assassination, Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537-1598 CE), the samurai and daimyo (a powerful feudal lord) who unified Japan in the 16th century CE, took on Rikyū as tea master and recent research has even concluded that Rikyū played an important role in government affairs (Bodart 1997). Sen no Rikyū, despite lord Hideyoshi’s lavish golden tearoom, advocated strongly for a more simplistic way of drinking tea through the wabi principles of “restraint and frugality'' aligned strongly with Zen Buddhist teachings of self-discipline that he learned from tea master Jōō (Hohenegger).

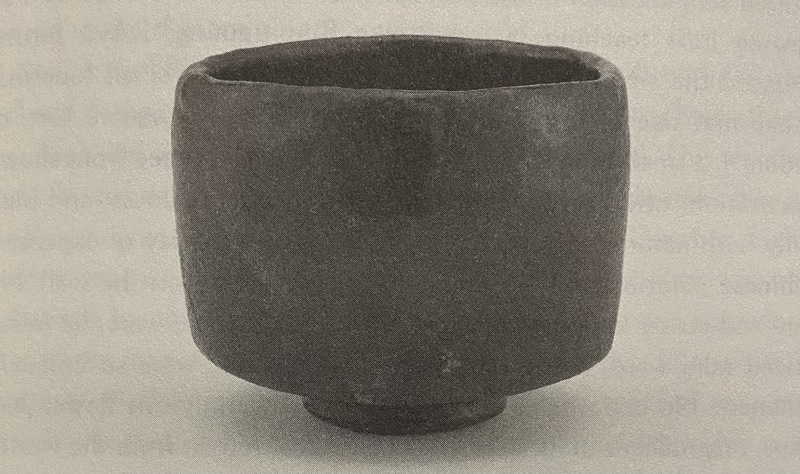

Rikyū transformed the tea ceremony in Japan completely, remaking it into a simplistic and humble practice. This transformation is seen in the tea ware he used; this tea bowl shown on the right is a collaboration of Tanaka Chōjirō and Sen no Rikyū himself in 1585-89 CE . Rikyū’s changes can be noticed immediately through the analysis of this bowl: he discouraged the use of fancy and expensive tea bowls from China, introducing simple, rough bowls fashioned by hand and not perfectly round (Towler). He even switched from a luxurious glaze to a rough deep red and black glaze that shows off the deep green of the tea. The man with which he collaborated to make this bowl, Tanaka Chōjirō (1516-1592 CE), was a potter and maker of roof tiles who worked occasionally with Rikyū to create bowls that were later named raku, derived from the seal inscribed with the character 楽, raku, that Hideyoshi presented Chōjirō in 1584 (Hohenegger). Rikyū's hand in creating these bowls was “vital to their introduction to chanoyu”, and the descendants of Chōjirō have passed down the art of creating raku bowls to this day (Wanatabe).

These simple bowls without decoration were meant to reflect wabi and Zen Buddhist ideals similarly to Rikyū’s other changes to the tea ceremony: Rikyū removed the decorations from the interior of room used to practice; he reduced the mat-size to about thirty-six square feet, less than half of what it was; and he eliminated the used of a door for guests of rank, the kininguchi, and made the main entrance, the nijiriguchi, small enough that it was necessary to crouch to enter the tea room (Hohenegger). His changes were meant to eliminate distractions and uphold an egalitarian space, creating a place of “peace and brotherhood, no matter how many wars were being fought outside” (Hioki 2013).

Rikyū did not hesitate to serve tea to high-ranking officials in his wabi hut instead of a fancier, shoin room as was common among the ruling class. Hideyoshi himself was said to have become a passionate wabi tea man under Rikyū’s guidance, with [as mentioned before] Rikyu also having his hand in governmental affairs. However, there was still some strife between the two, seeing as Rikyū had a confident, sensible spirit and was not afraid to stand up for his beliefs (Hohenegger, Driem). Sen no Rikyū was given a death sentence and commanded to commit ritual suicide (seppuku) by Hideyoshi, leaving historians to debate over the reasons behind this command (Towler).

However, Sen no Rikyū’s impact on Japan had already been completed. He succeeded in reverting Japan's tea ceremony from its superfluous, materialistic evolution back to its simplistic roots. His ceremony takes the art of drinking tea to a sacred level, where the host and guests share a moment of worship of the simple art of preparing and drinking tea together, fully in the moment (Towler). This idea of being present in the moment is a Zen practice in itself and connects the two on a spiritual level. And because of his high ranking government position, alongside his respected Zen and tea master reputation, he was able to spread his ceremony across Japan and immortalize the connection between Zen and tea in his ceremony.

His legacy lives on through the followers of Zen Buddhism and the practitioners of his tea ceremony, chanoyu, and is materialized through this image of the interior east wall in the Tai-an tea room taken by Lennox Tierney. It can be found in the Myōkian Temple, a Zen temple of the Rizai Sect, in Kyoto, Japan and is said to be a part of “one of only three [rooms] in Japan designated as National Treasures” (Lennox and University of Utah). The Tai-an tea room is the oldest of the three rooms, and said to have been the creation of Sen no Rikyū himself, with this particular wall dedicated to him. This wall, although seemingly not much to look at, stands for much of what Rikyu stood for: simplicity and sincerity. It’s fitting that instead of a great statue or landmark that a simple wall of a tea room with no decoration was with which his name was attributed, and its fame goes to show how revered he still is even today.