Transporting Across Borders: The Man with no Eyelids

It’s important to have a short understanding of the history of tea in China, to comprehend the extent of the connection between Zen, tea, and the monks to come. By the time Zen Buddhism was created, tea drinking had strong roots in the lifestyle of the Chinese people. Tea had become increasingly popular from the mid-T’ang era (618-907 CE) thanks to not only the “physical, physiological refreshment that [people] received from the tea”, but its “means of spiritual refreshment” (Sōshitsu 1998). And while traces of Zen Buddhism can be linked back to India, its formation as a practice originated in China [and is remembered to be associated] with a man named Daruma.

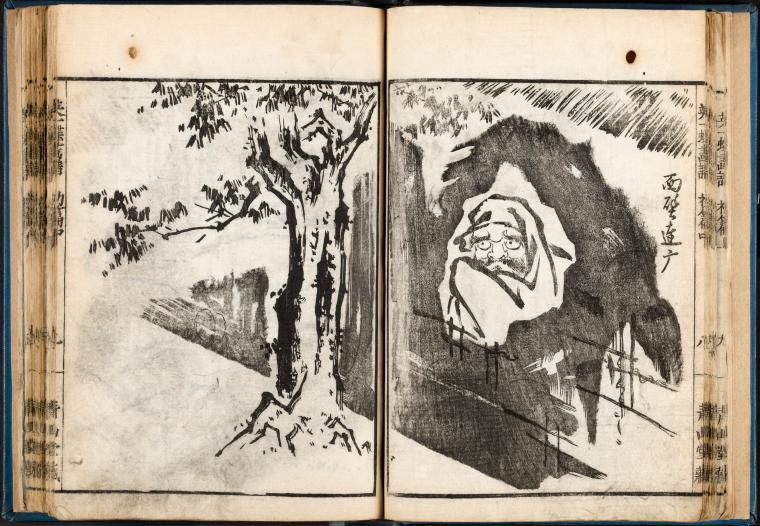

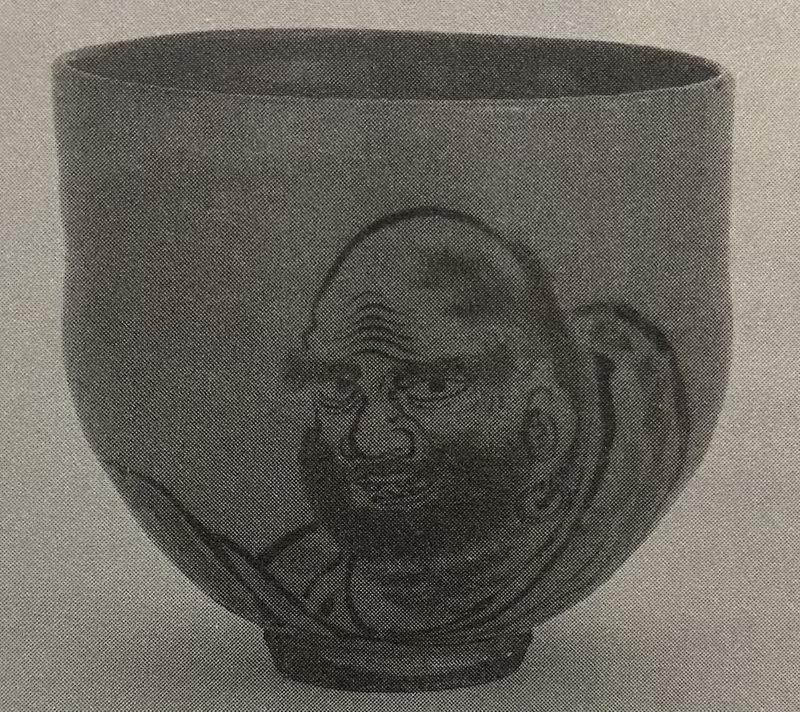

Daruma (or Bodhidharma in China) is said to have been a Brahman prince from southern India and a follower of the Buddhist doctrine of sudden enlightenment who lived during the 5th and 6th centuries CE (Hohenegger). The accounts of his life are largely shrouded in myth and have very few historical sources, but his unusual face has been immortalized in Japanese art and, specifically, on Japanese tea cups (as evidence of a quick google search). Like these two primary sources of a book illustration and tea bol show, Daruma was frequently portrayed as very serious, with great jutting or bushy eyebrows and a lack of eyelids (Towler).

Daruma's lack of eyelids outlines the first of many connections between Zen and tea: legend states that Darum once experienced a fit of anger after repeatedly falling asleep while attempting to meditate, and cut off his eyelids (Hohenegger). Upon touching the ground, his eyelids sprung up as a tea plant. This legend provided a folkloric view into a very real practice adopted by Zen monks of drinking strong tea in order to stay awake during meditation, which Daruma himself is said to have adopted (Towler). Another legend, illustrated in the picture of Daruma meditating by an unknown source, demostrates how he once stared at a cave wall for nine years, assumedly having drank tea to stay awake; this primary source having been created in 1770 CE shows just how important his legends have remained. Zen practices often included giving thanks to Daruma before drinking tea as well as imitating Daruma's tea habits to stay awake, and such practices are what the first Japanese monks took home with them after traveling to China (Hohenegger).

Returning to the tea bowl honoring Daruma on its surface, more can be said about the bowl’s connection to Zen Buddhism. Interestingly, the signature on the bowl attributed to the Japanese potter Okuda Eisen (1753-1811 CE) is said to be a false signature by the collector, but the bowl is still known to have been created sometime during the 19th century, from the region of Kyoto (Smithsonian). This specific Kyoto ware style is significant because it mimics the form of a raku tea bowl--with its straight sides, resting on a narrow foot ring--popularized by Sen no Rikyū in the 16th century CE, which I elaborate on the fourth page of my exhibit (Watanabe 2007, 88; Milne 2021). Whether this was a deliberate choice on the artist’s part or not is unknown, but the bowl’s resemblance to Rikyū’s raku bowl is interesting as it attributed Daruma’s legacy to later Japanese tea culture in the feudal period, keeping it alive despite more than a millennium later–whoever created it still acknowledges the well known connection between Daruma and tea.

Also, being a well known figure during his time, Daruma’s practices of tea drinking and Zen Buddhism were taught to many and amassed a following in China. Adopted by numerous monks was his practice of drinking tea to stay awake during meditation, as well as his “regimen of vigorous exercise based on the yoga principles” he’d brought from India after seeing in what poor shape his fellow monks were in (Hohenegger). Notably, this regimen, combined with mind discipline acquired during Zen meditation, developed into the practice of kung fu. It wasn’t long after that Japanese monks saw Daruma’s practices being performed in China and took them back to their home country along with the gift of tea seeds (Standage 2005, 129).