Immigration and Refugee Policies: Projects for Colonization

Projects for Jewish Colonization and the Influence of Public Opinion

On November 13, 1939, President Lázaro Cárdenas signed an agreement on agricultural colonization in Tabasco, enabling the settlement of 1,500 foreign families and an equal number of repatriated Mexican families in the township of Huimanguillo. Just four days later Excelsior, a newspaper of the Mexican capital, published an article entitled “One Thousand Five Hundred Families from Europe Are Going to Colonize an Extensive Region of Tabasco”. The article added information on the conditions stipulated by the Mexican government for the admission of the immigrants, and the provision that “among the new European immigrants there be families of different races and who profess different creeds. A large number of Hebrews would also be coming.” The publication itself is unsurprising given that the implementation of the Mestizaje national project culminated in an overwhelming distrust of Jewish immigrants entering the country, however the influence the article appears to have had is incredibly significant.

The same day that this information was published, when the representative of the government of Tabasco was about to get on a plane for New York to meet the representative of the immigrants, Governor Trujillo Gurría received a message from President Cárdenas, by way of the Ministry of the Interior, in which he deemed “it necessary to suspend momentarily the agreement pending the reaction of public opinion in relation to the publication of the news.” Cárdenas’ quick reaction here reveals not only that Jewish immigration was generally repudiated by public opinion, but also that such opinion had immediate influence on actual immigration policy. Mexican government officials involved in facilitating projects for Jewish immigration were aware of the potential negative public responses. This is evidenced by the fact that in general, all of those interested in the projects for Jewish immigration to Mexico were asked to deal with the matter very discretely, as reported by the JDC’s chief director, J. C. Hyman, based on his own experience: “The special settlement plan, presented by the aforementioned delegation, was very favorably received by President Cárdenas, but later it had to be postponed because we were advised that during the pre-election and election period, our plan should not be made a public issue.”

The projects for Jewish agricultural colonization grew out of the plan proposed by Beteta in January 1939, and served as the principal avenue for Jewish refugees to settle in Mexico. However, as the case of Tabasco reveals, most of these projects were doomed from the start. This point becomes clear when examining the most successful project that came out of this initiative: San Gregorio. In response to the immediate failure of a colonization project in Coscapá in March 1939, a ranch called San Gregorio, located thirty kilometers from Saltillo, Coahuila, became available as a potential avenue for several Jewish refugees to stay in Mexico. In September 1939 the Israelite Central Committee commissioned William Mayer to evaluate the viability of the project, and Rufino Monroy to carry out an agricultural study of the farm. The rather disheartening opinion of both was based on the determination that the ranch had serious problems obtaining water, and that agricultural work there could support at most four families. In spite of this, Mayer suggested the Central Committee back the project, especially to avoid the criticism of the government and the Jewish community. If the project were at least moderately successful, he argued, it could be proven to the Ministry of the Interior that Jews could adapt to agricultural life and that the committee was interested in helping them.

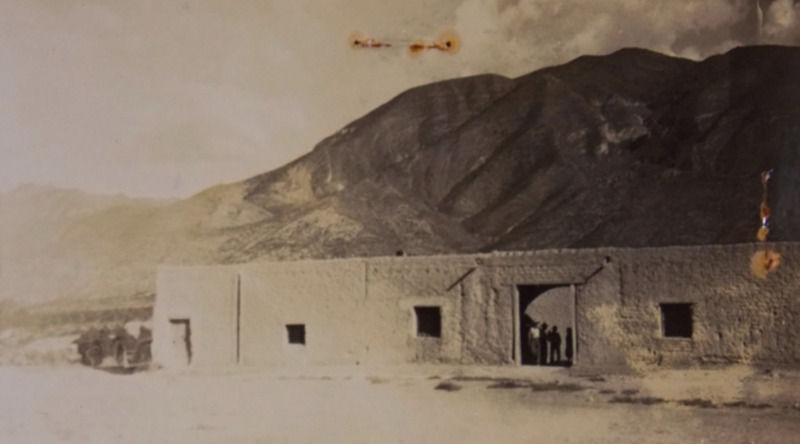

This photograph illustrates the infeasibility of the project from the start. The lands were extremely barren and had limited natural resources. Furthermore, the placement of the hacienda in the mountains reflects the intention of the Mexican government to place these Jewish colonies far away from the general population. For their part, the Jewish refugees that arrived in San Gregorio appeared enthusiastic and determined to make the project work. In figure 5b we can see the excited expressions on the faces of the fifteen men, and two women that were involved with the project. Despite his own reservations, Mayer himself recognized their enthusiasm, concluding that “[t]heir optimism may be due in part to their ignorance of the environment and the hardships of the land, as well as the fact that they had no other choice if they wished to remain in the country and later bring their families.” The attire of the people pictured here reflect this ignorance, as the professional robes do not seem compatible with what life on an agricultural colony would entail.