The Office of Inter-American Affairs (OIAA) and US Propaganda Posters

In 1947, Donald Rowland wrote The History of the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs as part of a series of U.S. government publications on World War II. The report tells the history of a short-lived U.S. government wartime agency between 1940 and 1946 (Rowland 58). It details the bureaucratic side of the Office of Inter-American Affairs, which became the powerful propaganda voice representing U.S. anti-Axis interests in Latin America during the war. As war broke out in Europe, policy makers in the United States began to identify new security concerns at home and abroad, and a propaganda campaign in Mexico and the rest of Latin America took on a new sense of urgency. The heightening of wartime hostilities revealed the vulnerability of the Western Hemisphere to Axis invasion and highlighted the strategic importance of many Latin American countries as suppliers of wartime materiel for Allied powers (Erb 108). Therefore, U.S. involvement in World War II coincided with new attention among government and business leaders toward Latin American countries and their role as defensive and economic allies. To combat Axis aggression and wartime economic turmoil, US government leaders implemented a policy aimed at forging hemispheric unity with the American republics.

By 1940 the Roosevelt administration understood that the acceleration of hostilities in Europe required a more aggressive cultural campaign in the Americas. In August, Roosevelt created the Office for Coordination of Commercial and Cultural Relations between the American Republics and appointed Nelson A. Rockefeller to lead the agency, and by 1942 it became the Office of Inter-American Affairs. Roosevelt and Rockefeller placed two main responsibilities upon the OIAA: First, the agency was to promote a closer cultural understanding between the United States and Latin America. Second, Rockefeller’s office took into account the growing pressure from U.S. businesses looking for economic and commercial security in a time of war and when the end of the war was in sight (Rankin 77).

Meanwhile, as the prospect of Mexico joining the war became more apparent, President Manuel Avila Camacho realized it would be in his country’s best interest to heal the strained relations between Mexico and the US that had been evident in previous years (Rankin 59). As a result, he moved the country closer to the United States by reaching important diplomatic agreements that established close commercial ties between the two nations. Thus, Camacho’s government worked with Roosevelt’s administration and Mexico’s Coordinating Committee began operation in October 1941 (Rankin 86). Most Latin American countries had national news services with relatively low circulation, but Mexico’s print media was generally more developed. OIAA officials were particularly concerned with the extent to which Axis propaganda seemed to proliferate in the national press. Although the British-led Inter-Allied Propaganda Committee had experienced some success in subsidizing major Mexican newspapers and influencing the nature of wartime information they published, US agents believed the Axis still enjoyed a stronghold in the nation’s press. The OIAA found that most Mexican newspapers relied on foreign press associations for war news. Frequently the services of US independent commercial press associations proved too costly, so Mexican newspapers turned to the Axis-subsidized associations. The German Transocean Agency, for example, frequently offered news features and photographs at reduced rates or even at no cost to Mexican periodicals (Rankin 87-8). This phenomena can help explain the widespread anti-Semitism throughout Mexican periodicals between 1933 and 1943. It is likely that Axis influence therefore contributed to the public opinion remaining resolutely against the idea of accepting Jewish refugees throughout this time. This joint initiative between the US and Mexican governments therefore constituted an attempt to shift Mexican public opinion. However, it is important to note that this was not an attempt to shift public opinion to a more sympathetic stance toward Jews and other victims of Fascist persecution, but rather it sought to spread US commercial culture.

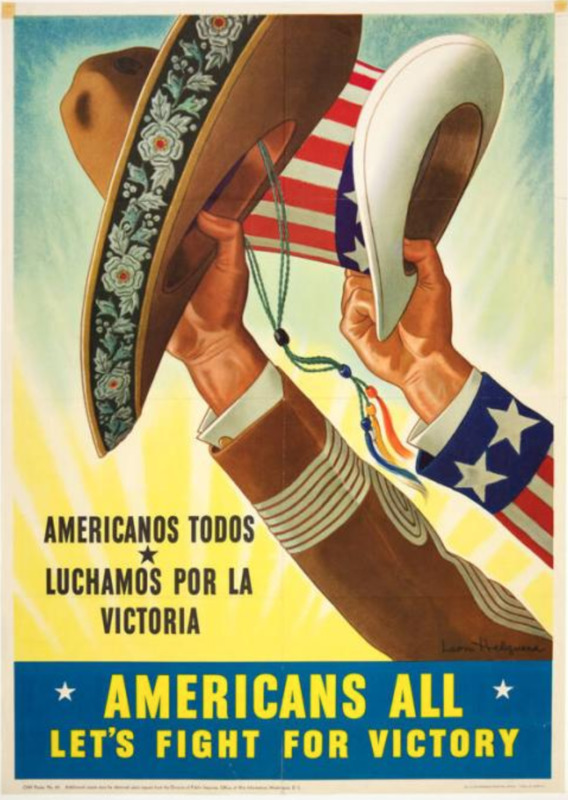

This propaganda poster, commissioned by the US government to be distributed throughout Mexican popular magazines in 1943 demonstrates the US government’s aim to promote unity between the two nations. For this particular poster, the US hired Leon Helguera, a Mexican commercial artist born in Chihuahua, Mexico (Friedman 138). Having moved to New York to become a naturalized US citizen in the 1930s, Helguera embodies the unique combination the US government was looking for: US patriotism and Mexican authenticity. Helguera’s use of the term “Americanos'' puts ordinary Mexican and US citizens in the same demographic category and emphasizes the hemispheric unity the US government sought to promote. Furthermore, the placement of the Spanish slogan: “Americanos Todos, Luchamos Por La Victoria” on top of the yellow sun creates a visual movement from the block letters to the image in the foreground. The use of a rising sun implicitly references the new age of cooperation and collaboration that characterized the Mexican-US relationship in the early 1940s.

While the American flag print that covers the shirt sleeve and hat makes the role of the US in the illustrated fight apparent, the fact that it is the man representing Mexico that appears in the forefront is significant, as it suggests Mexicans should look inwards for ideals of freedom and liberty, rather than toward an external source. Additionally, it is interesting that while Helguera uses the flag print to illustrate the US, he refrains from using the colors of the Mexican flag, instead using the sombrero to reference Mexican culture. During the 1930s, Mestizo agricultural workers often wore sombreros to mitigate the effects of the hot sun. Thus, the use of the sombrero to represent Mexico suggests it is the mestizos who encompass what is quintessentially Mexican. The poster therefore serves not only to emphasize the unity between the US and Mexico, but also to suggest that it is the mestizos who would ultimately lead the way to victory. While this is an effective message to promote Mexican pride and create popular support for Mexico’s participation in the war, its patriotic themes draw on the Mestizaje ideology that excludes many people, including Jews, from Mexican national identity.

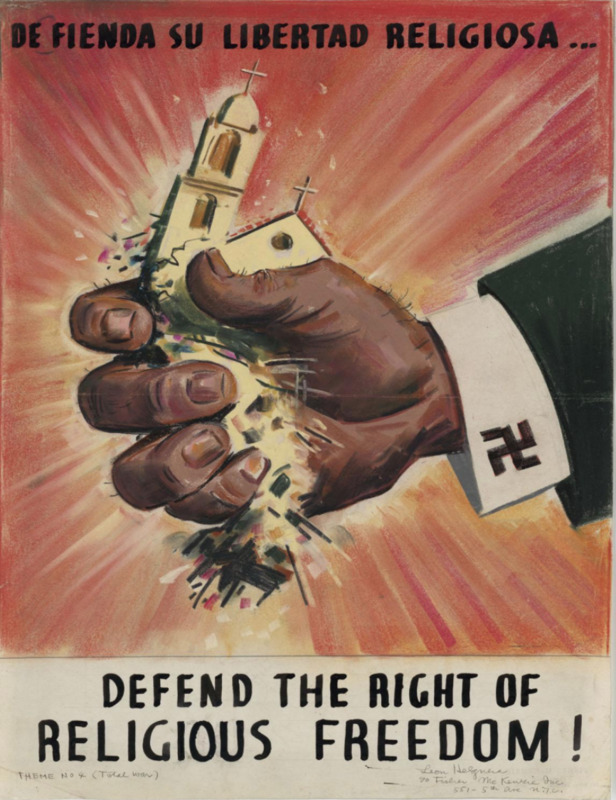

In this poster, Helguera takes a different approach, turning away from illustrating an explicit connection between Mexico and the US. Instead, Helguera appeals to the deep Catholic roots of the Mexican nation, encouraging Mexicans to rally behind the war effort to defend their traditions. Here, Helguera illustrates a large hand to represent Nazi Germany, as indicated by the swastika on the cuff. In a powerful display of force, the hand crushes a Catholic church in a clear reference to the Catholic persecution in Nazi Germany. While the bottom of the church is clearly demolished, the top remains intact, with the crosses standing firm. This would imply to Mexican readers that with their support, the freedom to participate in the Catholic faith could still be saved. This is significant because it references the victims of Nazi persecution explicitly, demonstrating a desire among US government officials to evoke sympathy from the Mexican public for the victims of Fascist persecution. It is therefore significant that Helguera intentionally chose to center the Catholics as the primary victims, and make absolutely no reference to Jewish persecution. Helguera knew emphasizing the persecution of Catholicism would be a much more powerful tactic in rallying Mexican support for the war. This tactic once again emphasizes Mexican traditions, and puts them at the forefront of the fight for freedom. Centering the focus on Mexican Catholics thereby serves to exclude other groups from the fight.

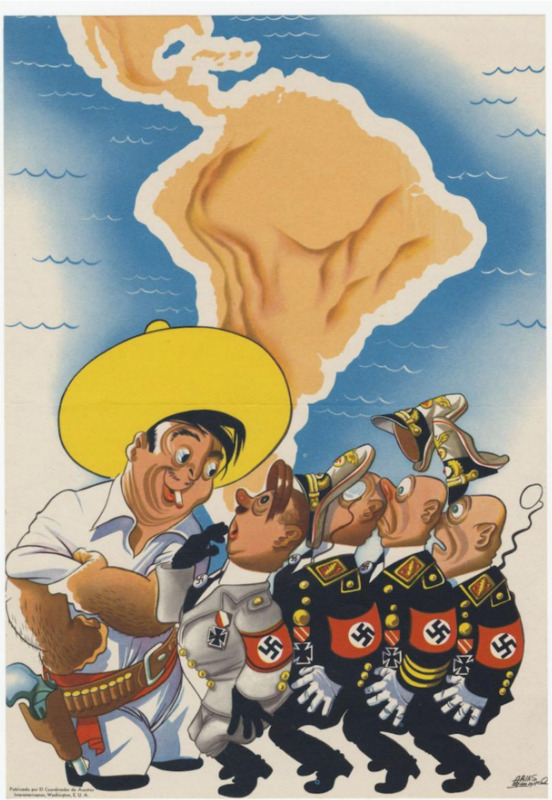

This last poster is another one in the series created by Antonio Arias Bernal in 1943. For this poster, Bernal decided once again to feature a map in the background of North and South America, but this time he only depicts Mexico on the continent of North America, excluding the US from the implied pan-American sentiment and underscoring Mexico as the representative of North America. Illustrating the Nazis encroaching on Latin American territory shifts attention away from the threat of persecution from the victims in Europe to the potential impact Nazism can have in the western hemisphere. Once again, Mexico is represented by a Mestizo man, centering ordinary Mexicans at the front of the fight, and encouraging their participation as protectors. As we discussed earlier, the Mexican government decided that their propaganda should avoid making close connections between Mexico and the United States in the context of the war, and instead emphasize that Mexicans should support the war effort in the interest of protecting Mexico’s well-being. Since Antonio Arias Bernal was living in Mexico when he produced these posters for the US government, it is likely that he was aware of this decision, which is why we can see that intention reflected here. Thus, the mestizo man is confronting the Nazis for the expressed purpose of benefiting Mexico, rather than the US or Europe.