Khmer Rouge

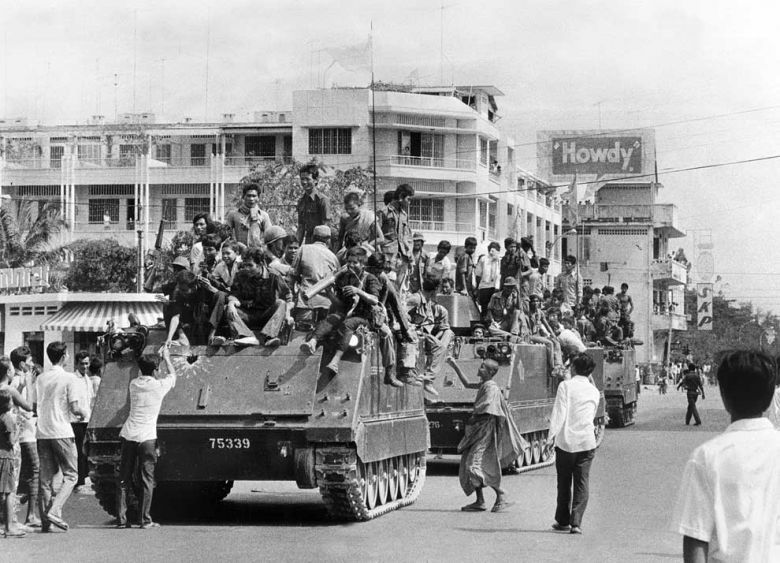

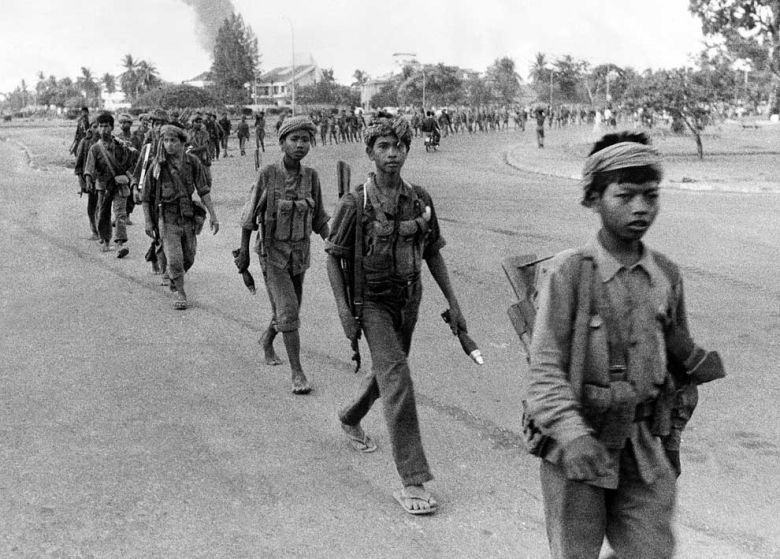

When the Khmer Rouge came to power in April 1975, Cambodia was turned upside down; cities were evacuated, families got separated, religious worship was banned, and markets were shut and destroyed (Shapiro-Phim 8). The leadership of Khmer Rouge under Angkar or “the organization” aimed to geared Cambodia to become a self-reliant, agrarian, socialist state (Shapiro-Phim 180). About a quarter of the population, close to two million people, lost their lives due to overwork, starvation, disease, torture, and execution, under the four years rule of the regime (Shapiro-Phim 181). The attempt to erase all traces of Khmer civilization involves the elimination of potential traitors, anyone who appears to be educated and is associated with the essence of Khmer culture including teachers, bureaucrats, dancers, and those who wore eyeglasses which are often associated with having gone to school (Lyons, 53).

During the regime, songs and dances became an instrument used by the Angkar in their battle of manipulation, where they created and display revolutionary songs and dances and banned any other types of performances that belong to prerevolution (Shapiro-Phim 180). With its strong association with the state, and thus with previous regimes, classical dance along with the dancers were part of the main target of Khmer Rouge. An estimation of about 80-90 percent of the members of the Royal Ballet of Cambodia lost their lives due to execution, malnutrition, and forced labor (Nut 280).

Post-Khmer Rouge: 1979

It is still a firm belief that Khmer Classical Dance remains an important artistic expression of Cambodia’s cultural identity (Nut 280). The surviving dancers who managed to escape execution had either posed as peasants or got into refugee camps along the Cambodian-Thai border (Hamera 72). At the refugee camps, Cambodians gathered and taught each other basic Khmer Classical or Khmer folk dance movements that they knew and even staged small performances (Shapiro 8). According to Toni Shapiro, when talking about the making of an art documentation project, Cambodian dancing troupes that were based in the refugee camps viewed Classical Dance as the most important and thus should be the priority in the project (9). Classical Dance was referred to as the “soul” of the Khmer People, a symbol of connection to the past and to what it means to be “Khmer” (10).

After resettling in foreign countries, Cambodian immigrants continue to teach music and dance in their own communities as a way to preserve the art and some even went back to Cambodia to aid the restoration process (Diamond 126). Cultural organizations such as Apsara foundation school and Cambodian dance companies such as Dance Celeste were efforts to preserve the arts of Classical Dance (Hamera 78).