Foreign Aids, Tourism and Mass Media

Domestically, the dissolution of the royal dance troupe of classical dance during the Khmer Rouge had brought the dance closer to the common people, where exiled teachers taught interested students, an action that signaled a change in attitude towards the dance in terms of its association with the monarchy (Diamond 153). Although the monarchy was reinstated later in Cambodia, classical dancers were trained and supported by the government and not by the royal family, which is unlike any other era (Shapiro-Phim 9). Decades of war and turmoil had weakened the influence of the court dance, making it not as integral of the people’s lives as in the past (Diamond 154). While there were opportunities to perform internationally, engage in exchange programs, and represent the monarch in special ritual ceremonies, dancers still had to find extra jobs to make ends meet due to their salaries being too low (Shapiro-Phim 65). Due to poverty having greatly weakened the involvement in performing arts, few jobs are available and foreign support is seen as the dancers’ only hope in preserving the art (Diamond 124). However, the reliance on foreign aids has its impacts when foreign NGOs dictate the style or content of the delivery of traditional arts made relevant to contemporary issues such as reproductive health and HIV prevention (125). In addition, foreign projects that are about Cambodia seem to only focus on the Khmer Rouge regime, making it feels like the artists will never be able to escape the narration and horror of the era (125). Although projects like these are financial supports for classical dancers, the foreign aesthetic embedded in it turns out to be difficult for the dancers to negotiate (125).

In addition to foreign aids, another form of financial support that classical dancers turn to is the tourism industry (Tuchman-Rosta 525). Classical dancers who previously performed only for the royals and VIPs had to find work at hotels and restaurants while other types of dances are preserved by family troupes or farmers who practice in the non-planting seasons (Diamond 124).

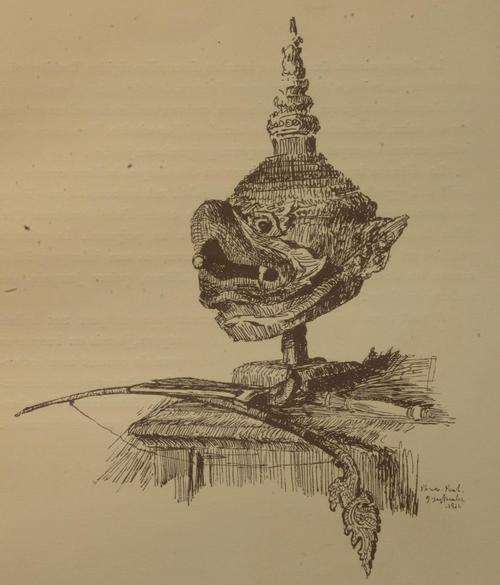

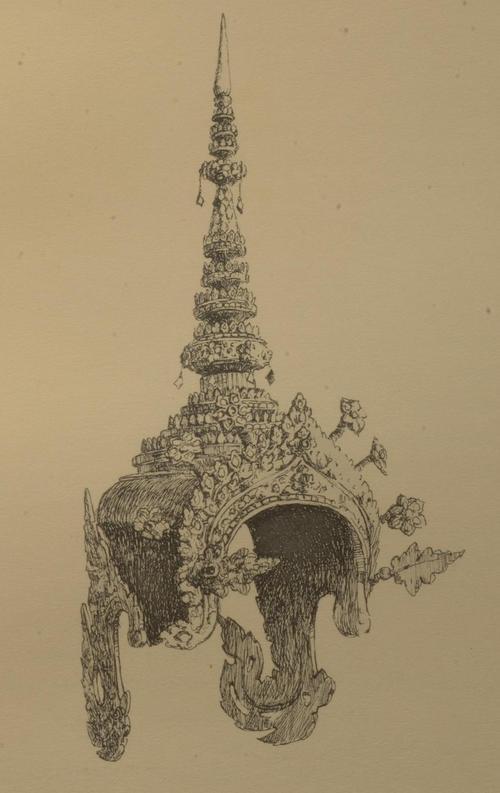

Although there were contested views about using the sacred dance as a tourist attraction due to worries of being disrespectful to the art, more emphasis on the value of cultural performances to the economy soon became the main focus instead (Tuchman-Rosta 525). Dancers at Siem Reap, Cambodia’s most famous tourist attraction, typically perform as evening entertainment at markets, restaurants, dinner-buffets, and at the Cambodian cultural village, earning a monthly salary of about $30-45, $45-80, and $80-300, respectively (529). In classical dance, the connection between Kru or (dance teacher) and the student (dancers) is really important, dancers can wear the mask and costumes of the role she would be performing only after she completes an annual ‘sampeah kru’, a ceremony dedicated to the dance teacher and to spirits for permission to perform the dance (Cravath 582). Students would never wear a mask or headdress by themselves, and when the teacher placed the mask or headdress on the students, the students thus received the spirit of the mask from the kru (Cravath 198).

However, some of the performances in Siem Reap, especially those at dinner-buffets, do not have dance teachers coming to oversee the performance (Tuchman-Rosta 534). Some classical dancers in Siem Reap even mentioned that technique level, prayer before a performance, and the absence of a teacher is not of particular concern, pointing out a perspective of viewing classical performance as merely a job like any other performance (Tuchman-Rosta 534).In the documentary “The Royal Cambodian Ballet: Dancing for the gods'', Lok Ta Chheng Ponh, former minister of the ministry of culture stated “As far as I know, classical dancers never danced for money. They do not dance to serve normal people. They dance for the essence of purity. To have the dancers perform and use their beauty like this is a great sacrifice” (42:07-42:38). It seems that although Classical dance remained a source of identity in Cambodia, its ritual and spiritual essence is being neglected due to the usage of it as a tourist attraction.