Savages at the World Fair: The Bontoc Igorrotes

The Suk'-lâng

Starting around the age of six or seven, the suk’-lâng is worn by boys of the Cordillera mountain range (Jenks, 1904). It is worn on the back of the head and held in place by a cord across the forehead (Jenks, 1904). When it rains, the suk’-lâng is not taken off but continues to be worn, though covered by a separate rain hat (Jenks, 1904). Hair length dictates the headwear worn by men, as long-haired men wear the suk’-lâng with the long ends of their hair tucked into the hat, while shortly having two or three brass rings attached to the outside of the hat, though may be decorated with various items such as animal teeth, pearl shells, human hair, army buttons, and brass wire, among other things (Jenks, 1904). These adornments can signify the status of the wearer, showing relationship availability, village affiliation, or whether they are a successful hunter of men (Linker, 1961).

While the suk’-lâng is from the Philippines, it possesses influence from various surrounding cultures. Favored material choices, such as bamboo, and particular weaving techniques in various hats hail from Southeast Asia, while other techniques and style decisions take influence from China and Malaysia (Linker, 1961). Many hats were made by Chinese-run hat factories which were commonly present on the Luzon coast at the time many of these Philippine hats were extracted (Linker, 1961). American colonial presence explains the influence in the design of some Cordilleran peoples’ hats, including the use of army pins featuring American eagles being sewn onto the top of some suk’-lângs as decoration (Linker, 1961).

The St. Louis World Fair

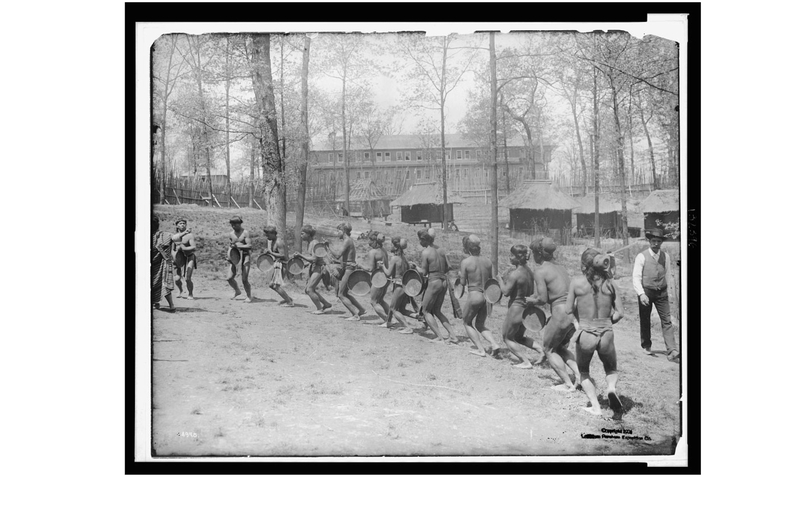

The 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition, also known as the St. Louis World Fair was a mark of America’s spreading colonialism. Exhibits at the World Fair were meant to be sensational and show off American innovation and expanding cultural achievement (Rydell, 1984). Along with bragging about all America has accomplished and confirming its superiority, exhibits were pushing racist ideologies, comparing foreign cultures to America’s cultural progress (Rydell, 1984). The fair was presented as a place of education and American development while presenting exhibits that were politically biased and furthered colonial ideals. The world fair, as indicated by the name, brought the world to people, showing fairgoers things that were previously inaccessible. As a result, people’s only perception of the cultures presented was the distorted version created by the fair. This portrayal of Filipino people justified America’s colonial beliefs and consequential colonization of the Philippines, and the general expansion of America, such as the Louisiana Purchase (Rydell, 1984).

As a self-anointed educational place, the fair turned a culture into an anthropological study and people into zoo displays. The fair followed a two-layered classification scheme created by F. J. V. Skiff (Rydell, 1984). The border categories consisted of departments of study, the linchpin department being Anthropology (Rydell, 1984). Within this category, exhibits were ordered sequentially by human development and progress (Rydell, 1984). What is really meant by human development and progress is that people were divided along racial and cultural lines, being labeled as savage, barbaric, civilized, or enlightened (Rydell, 1984). This system of presentation was meant to highlight the benefit of American presence in the Philippines, advertising the potential cultural improvement that could result (Rydell, 1984). Along with pushing the narrative of racial inferiority, there was an underlying message of proving the value of the Philippines to America’s economy (Rydell, 1984). All these factors in the layout of the fair and exhibits were intentional to justify the larger goal of America’s colonization of the Philippines.

The Indigenous People of Cordillera

At the St. Louis World Fair, the most primitive group on display were the Igorots, or more properly referred to as the Cordilleran peoples or Ifugao. They were labeled as “dog-eaters,” “cannibals,” “black hornets,” and “headhunters” among other offensive names (Fermin, 2004). False stories were purposely spread about the Cordilleran peoples to perpetuate the idea that they were barbaric and uncivilized. Though the Bontoc people eat dog for ceremonial purposes, news spread that dogs were part of their regular diet and that the Bontoc people would sneak out of the fair during the night and capture dogs for consumption (Fermin, 2004). Debate on how they ought to be dressed at the fair was another topic of controversy (Fermin, 2004). The Ifugao do not dress as Western people do, covered from the neck down, but generally wear a girdle or skirt. Their style of attire sparked outrage at their “improper” dress and further proved their savage nature (Fermin, 2004). While there was a call to cover them up, many believed it would impede the authenticity of the exhibit (Fermin, 2004). Despite their unpopular so-called primitive behavior and dress, they were not believed to be beyond help, but in fact, had much hope for improvement.

Violent Imperialism

Filipino people were exploited at this fair to push agendas that aimed to destroy their own home country and demean their culture. Disguised as an anthropological and educational place, fairgoers learned only imperial values and white supremacy. The entire fair served as a legitimation for a war colonizing the Philippines while touting white savior notions of improving their people. Every aspect of the fair was thought out and manipulated, from the layout, to the classification system, to the marketing, and the presentation of the people themselves to present the indigenous people of the Cordilleran Mountains as savages who needed to be helped, and the Philippines in general as a valuable economic resource for America to take advantage of. Human zoos are dehumanizing and allowed people’s existence to be a topic of controversy. The St. Louis World Fair was degrading and cruel on a personal level to the Filipino people who were forcibly showcased and corrupt in its exploitation of indigenous people to defend the destruction of their own land and people. As the world moves forward, it is crucial to reflect on the past and understand how colonial beliefs continue to exist in many forms today, and morph to hide in plain sight. The sensational St. Louis World Fair did not bring the world to people but crafted a prejudiced and limited understanding of the world to promote American superiority. It was a form of violent imperialism.

References

“Expedition Magazine | Philippine Hats.” n.d. Expedition Magazine. Accessed November 15, 2023. https://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/philippine-hats/.

Fermin, Jose D. 2004. 1904 World’s Fair: The Filipino Experience. Diliman, Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

Jenks, Albert Ernest. 1904. “Bontoc Igorot Clothing.” American Anthropologist 6 (5): 695–704.

Rydell, Robert W. 1984. All the World’s a Fair: Visions of Empire at American International Expositions, 1876-1916. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.