'Egyptomania' and British Colonialism

The European theft of Egyptian culture

As you walk around the museums of the modern day you are taken aback by the vast array of Egyptian items; anything from jewelry and paintings, to their dead. While at first you sit there and think about the beauties, incredible feats of time, and fascinating history of the rich culture of Egypt, at a certain point you must question, how did these items get here? Behind that question is a long history of theft and colonialism.

History of the collection

The theft of Egyptian artifacts can be atributed to Napoleon and the French invasion of Egypt starting in 1798. On June 1st, 1798 the French landed in the mouth of the nile at Alexandria where they quickly took control over the city. The French moved to Cairo where the British were waiting. The British quickly destroyed the French fleet but nevertheless Napolean decided to continue on into Palestine where the Ottoman Turks and British defeated them as well. Although it was not a successful invasion, it had a large impact on the perception of French power. The French decided to shift focus away from the loss and towards the influence of Egypt where France took an interest in the culture in a phenomenon known as Egyptomania.

Colonial Extraction

From 1880 to 1915, also known as the British Colonial era, groups were created to collect and steal objects throughout Egypt such as the Egypt Exploration Fund (EEF), the Egyptian Research Account (ERA) and the British School of Archaeology. The EEF in particular was established ‘for the purpose of excavating the ancient sites of the Egyptian Delta’. Donors would request the collection of artifacts to expand their collections which were dispersed across the world throught these organizations. These items, similar to items stolen by other groups, were unevenly distributed and oftentimes even separated within collections. Tomb-groups; items grouped based on what tomb they belonged to, were continuously separated and rarely kept intact, various museums and groups would have ownership of the contents of a single tomb-group. A prime example of this are the items Lafayette College owns in its Special Collections.

A piece described as a wooden coffin fragment that has numerous large hieroglyphs painted on it (Figure 1), has a very brief history of ownership only being described as being ‘gifted’ to Lafayette by Dr. Dominic Mariano, other than that there is little to no information on the object. This object is a fragment of a once large cohesive story, but now we are left to interpret no more than the symbols on the piece of wood; this is a common tale with many Egyptian artifacts. As Egyptian excavations rose in frequency, so did excavation throughout many areas of the world. The partage system was put into place by the French head of the Egyptian Antiquities Service, Gaston Maspero, to divide the artifacts found and send them to different archaeological museums. This is an inherently colonial system as the people putting these rules into place were not the same people who had true cultural ownership over the items. Western institutions and museums were taking claim over items owned by the Egyptians. For example, the University of Michigan began its excavation in 1924 through the partage system where Howard Carter discovered the tomb of Tutankhamun. Carter's deal with the partage system gave him the rights to so many artifacts it spanned a 50 page document. The contents of Tutankhamuns tomb were split up between a number of different institutions; this happened continuously at the hands of the partage system.

While assessing the impact the massive amounts of theft had on not only the history of Egypt but the culture left in their own country it is hard to realize quite the magnitude of dispersion. To put into perspective the scope of objects stolen, University of Oxfords Pitt Rivers Museums collection consists of nearly 62% Egyptian artifacts; as well there are more than 112 collections of Egyptians items in the UK alone. No other region of the world is emphasized in museums as heavily as Ancient Egypt. Because Egyptian items have become the focal point of museum culture it has caused a division from the modern Egyptians and modern day as we know it (Abd el-Gawad and Stevenson 2021). Groups like the EEF and BSA did a poor job of documenting where the items even went across the world. Trying to reconstruct the timeline of events and rebuilding collections becomes near impossible when you don’t know what items there are and aren’t to be found. Oftentimes the EEF descriptions of items would only list where the item was from and what year it was distributed; this would lead to museums having many more items than were recorded. Rebuilding the Collection The Director of Egyptian Ministry and antiquities department, Shaaban Abdelgawad, stated that there was a near complete absence of records of the artifacts stored and displayed outside Egypt (Shehata, 2016). Egypt still has to rely on Western countries' documentation to try to piece together their history, particularly when they are trying to distinguish what has been stolen from them and what was given through gifting agreements. Egypt has been the center of many recent movements surrounding cultural theft and artifacts in the Western world. Much of the discussion is centered around whether the items should be completely returned to Egypt, or whether they should remain outside of the country to boost education and tourism to Egypt.

Egypt has become so far separated from their own history they are barely able to claim it as their own, even within the spaces created by their country. For example items and materials cataloged within Egypt have been documented using Classical Arabic as opposed to Egyptian Arabic.

Reclaiming the Past

In very recent years there have been numerous movements to reclaim Egyptian culture. The Egypt’s Dispersed Heritage Project launched Perry’s EMOTIVE project which aims to connect modern Egyptian locals with their culture by connecting with archaeologists to provide raw materials that they can then interpret for themselves. Perrys has claimed there is inherent enchantment in archaeology that just needs to be found in the right places; many people disagree with this claim though as the entire archaeological system was founded on taking advantage of the Egyptian people and removing them from their culture. The EDH has instead tried to put the project of reclamation back into the hands of Egyptian locals. They have begun to train western museums on the exploitation of Egypt and communicate with locals solely in Egyptian Arabic to begin involving them more closely in the process. While undoing what has been done to the Egyptian people is sadly a task that will never be completed, it is very important that western institutions start to take responsibility over the damage they've done. There is still potential to educate the general public and for items currently in circulation and those being viewed around the world to be reclaimed. Reconnecting Egyptians with their culture is a responsibility museums around the world have in their hands.

Bibliography

Abd el-Gawad, Heba, and Alice Stevenson. “Egypt’s Dispersed Heritage: Multi-Directional Storytelling through Comic Art.” Journal of Social Archaeology 21, no. 1 (2021): 121–45.

Reid, Donald M. Whose pharaohs?: Archaeology, museums, and Egyptian national identity from Napoleon to World War I. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2003.

Stevenson, Alice, and Alice Williams. “Blind Spots in Museum Anthropology: Ancient Egypt in the Ethnographic Museum.” Museum Anthropology 45, no. 2 (2022): 96–110.

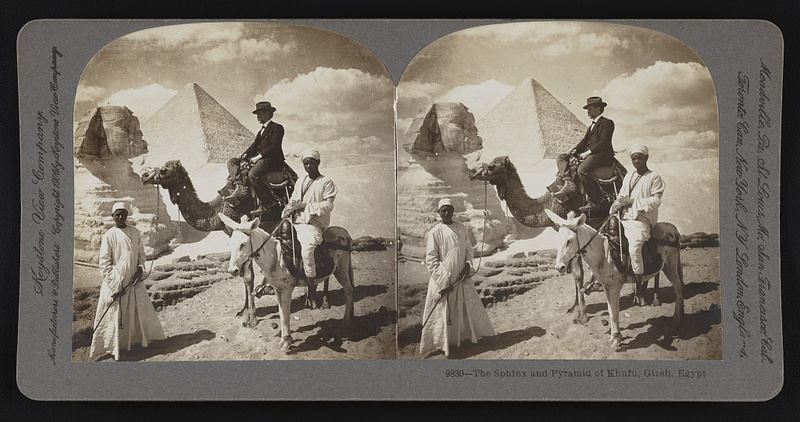

Stevenson, Alice. “Artifacts of Excavation.” Journal of the History of Collections 26, no. 1 (2013):89-102 Keystone View Company. The Sphinx and pyramid of Khufu, Gizeh, Egypt. Egypt Jizah Jīzah, ca. 1906. Meadville, Pa.: Keystone View Company. Photograph. Gertrude Bell Archive.

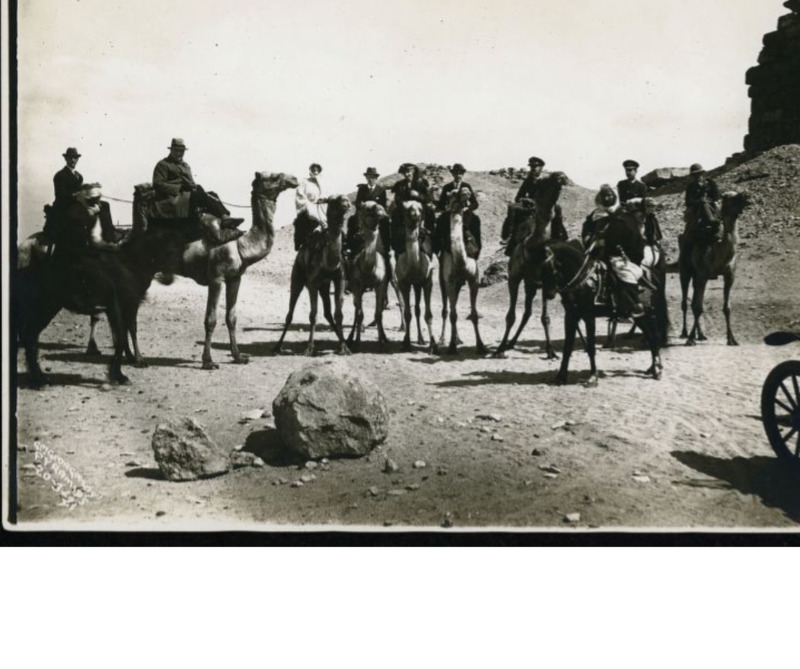

Group photograph of attendees at the Cairo Conference including Gertrude Bell and Winston Churchill, Cairo, Egypt. ca. 20 March, 1921. Photograph. Haug, Brendan. “Politics, Partage, and Papyri: Excavated Texts between Cairo and Ann Arbor (1924–1953).” American Journal of Archaeology 125, no. 1 (2021): 143–63.