Collecting and Exhibiting the 'Semi-Civilized': The 'Moro Village' at the St. Louis World's Fair and The Making of an Ideal Colonized Subject

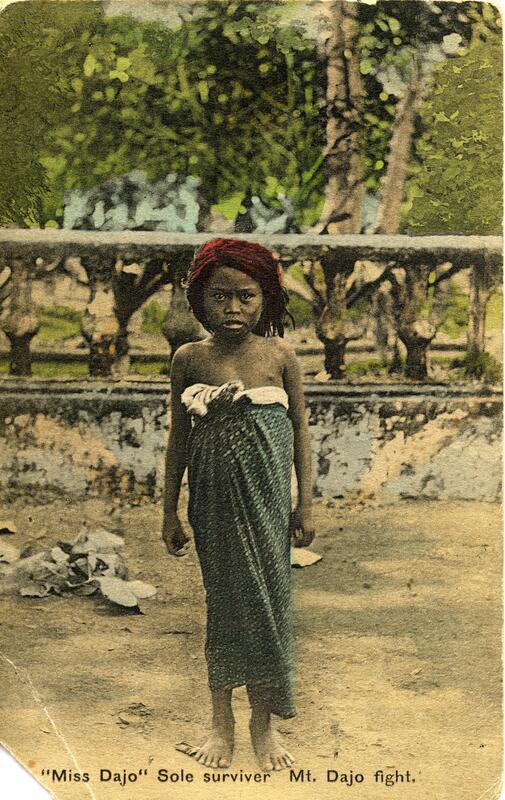

"Moro," Spanish for "Moor," refers to the indigenous Muslim population on the island of Mindanao and in the Sulu Archipelago in the southern Philippines. Comprising thirteen distinct ethnolinguistic groups, including the Palawan, Sama, Tausug, and Yakan (Hawkins 2020), the Filipino Muslims have a long history of resisting Spanish colonization and U.S. colonial rule following the Philippine-American War (1899-1902). In an effort to quell resistance, the U.S., aiming to establish control over the islands, signed the Bates Treaty with the Sultanate of Sulu in 1899. This treaty, affirming autonomy and religious freedom in Muslim-dominated areas, was intended to prevent the indigenous Muslim population from joining the Philippines Liberation Army's fight for independence in the North (Faye 2015; Immerwahr 2019). However, this promise of autonomy was short-lived. Once the Northern Philippines was under U.S. control, the colonial officials implemented full American military rule in the South, establishing the "Moro Province" (James 2011; Hawkins). Between 1902 and 1913, the U.S. Army aggressively suppressed Muslim resistance, culminating in the 1906 massacre at Bud Dajo on Jolo Island, where over 600, predominantly women, resisters were killed (Hawkins 2011). Artifacts such as the Kurab-a-kulang (on display in this exhibit), worn by Muslim combatants, were collected by the U.S. military as war souvenirs, alongside images depicting these violent encounters.

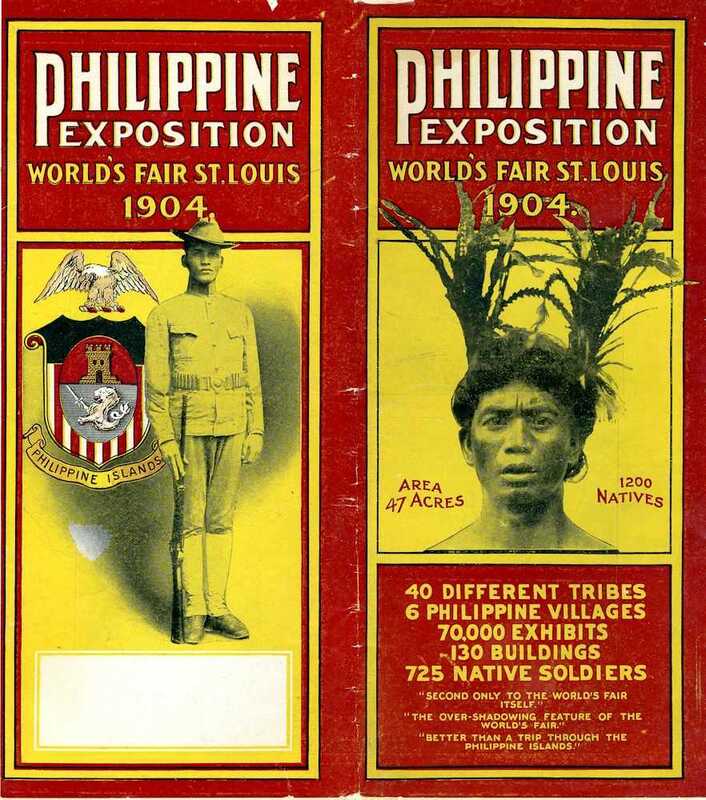

Parallel to the military efforts, U.S. colonial authorities embarked on cultural campaigns. Starting in 1902, American officials in the Philippines began organizing exhibits for the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, popularly known as the 1904 World’s Fair, in St. Louis, Missouri. Governor-General William Howard Taft of the Philippines issued a circular to the Exposition Committee, urging military and administrative personnel to “join their efforts…in procuring superior exhibits which shall well represent the past and future as well as the actual state of economic and social development of the Philippines” (Hawkins 2020, 1). These exhibits would be instrumental in framing the narrative of Filipino Muslims, portraying “images of Muslim savagery and pristine primitiveness,” which were “carefully preserved, domesticated, and reproduced.”

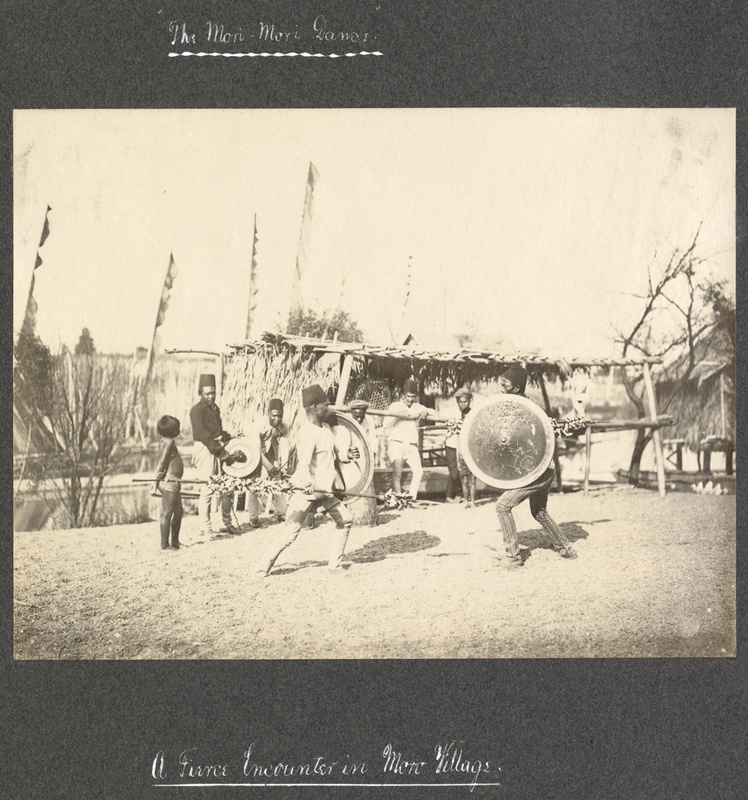

The “Moro Village,” showcased as one of the eighty "live exhibits" at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition, further entrenched stereotypes highlighting the Moros' martial nature and their potential evolution towards modernity. This display featured 80 Samal and Lamao individuals, depicted as noble yet fierce warriors, and labeled as "semi-civilized." This portrayal epitomized colonial views of progression from savagery to barbarism, and ultimately, civilization (Hawkins, 2020). The designation of Moros as "semi-civilized" served as a "cultural technology of tutelary empire," aimed more at educating the citizens of the metropole than those of the colony. Their apparent lack of clothing, technology, sanitation, and political culture, coupled with a portrayal of "passivity" disrupted by sensational displays of controlled savage violence and distasteful social practices, sharply contrasted with the fair's "bourgeois fantasy world" of abundance. This juxtaposition reinforced the notion that the Philippines' significance to the United States was more moral and exemplary than strategic or economic. The public was thus nudged towards embracing modern standards of civility and taste, distancing themselves from their antithesis (Hawkins, 2020).

Through this “pedagogy of imperial anthropology” (Hawkins, 2020), Moro daily life was exotically portrayed. Moreover, these exhibits transformed Moros into an "ethnological, sociological, and political category," fitting neatly into the American narrative of enlightened governance. This systematic representation allowed the U.S. to obscure the harshness of its colonial rule, justifying its occupation of the Philippine Islands as a form of benevolent guidance (Hawkins, 2020). The conclusion of the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition marked not just the end of an event, but the beginning of a new chapter in the display of colonial conquests. Many artifacts featured at the World’s Fair, now residing in the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, serve as poignant reminders of the U.S.'s imperialist ambitions in the Philippines. These objects, much like others acquired during colonial expeditions, are not mere artifacts; they are tangible representations of the colonial and imperial projects. Their presence in the museum underlines the complex and often troubling history of how such items were collected, portraying a narrative of power, subjugation, and the transformation of cultures under colonial rule. As such, these artifacts from the Moro people offer a critical lens through which American imperialism can be examined and understood.

Reference List

Arnold, James R. 2011. The Moro War: How America Battled a Muslim Insurgency in the Philippine Jungle, 1902-1913. Bloomsbury Press.

Caronan, Faye. 2015. Legitimizing Empire: Filipino American and U.S. Puerto Rican Cultural Critique. University of Illinois Press.

Hawkins, Michael C. 2011. "Managing a Massacre: Savagery, Civility, and Gender in Moro Province in the Wake of Bud Dajo." Philippine Studies 59, no. 1: 102.

Hawkins, Michael. 2013. Making Moros: Imperial Historicism and American Military Rule in the Philippines Muslim South. Northern Illinois University Press.

———. 2020. Semi-Civilized: The Moro Village at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition. Northern Illinois University Press.

Immerwahr, Daniel. 2019. How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Rydell, Robert W. 1984. “The Louisiana Purchase Exposition, St. Louis, 1904: The Coronation of Civilization.” In All the World’s a Fair: Visions of Empire at American International Expositions, 1876-1916, 154–83. University of Chicago Press.