Tsitsistas/Suhtai (Cheyenne) Moccasins

Introduction

Moccasins are often recognized as a hallmark of Native American culture for their utility and their careful craftsmanship. Although moccasins and Native American culture appear synonymous in both historical depictions and popular culture, this sentiment has been implemented in the American psyche as a way to understand a distinctly “primitive” culture. Moccasins and other Native American garments became interesting to anthropologists only as they decided that the Native American culture was declining. Yet, while collectors and anthropologists acted as though they were preserving indigenous cultures, the U.S government was actively massacring Native Ameircans as well as engaging in forced relocations and assimilations (Redmen 2021,124). Anthropologists, explorers, and collectors did not reconcile the fact that the United States government was actively decimating these populations, instead used it as an opportunity to play a white savior role that could properly protect these artifacts that represented a by-gone time.

The beaded, leather Tsitsistas (Cheyenne) moccasins with a geometric design are a quintessential example of the exploitative course Native American objects endured on the way into a museum. The moccasins were found in American artist and illustrator Howard Chandler Christy’s papers, owned by the Lafayette College Special Collections & Archives. The collection documents the personal life and career of Christy which includes sketches, documents, artwork, and miscellaneous ephemera that was found in the studio of Christy after his death.

The Salvage Project

Salvage anthropology is the idea that anthropologists collected and extracted the material cultures of indigenous tribes in the United States as well as globally in order to study indigenous cultures. The ideology that the materials of these people are in need of preserving stems from a deeply racist outlook, as anthropologists believed they were the only ones who could maintain these artifacts as indigenous cultures would soon disappear (Simpson 2018). Salvage anthropology makes the assumption that Native American cultures were dying out and representative of the past. In no way does it attempt to recognize the survival or sovereignty of Native American culture or that their communities still exist. The underlying issue therefore, is not just the violent removal of the objects, but also in the fact that they were understood as artifacts by anthropologists and well as the U.S government. Perceiving the cultural objects of Native Americans proposes the idea that they are separate from mainstream American culture and they are from an earlier time that is rapidly fading away (Redman 2021, 2). However, in reality the United States was stealing the land of the tribes, massacring their people, and using forced assimilation to completely eradicate their heritage to then be able to steal their objects for study and exhibition, fueling the museum system.

Salvage Anthropology in Fine Art and Museums

Expeditions to study Native Americans were widespread as the United States sought to expand their territory west and create legislation that further exploited and destroyed Native American populations. Through the extraction of materials from these tribes, the men studying the indigenous communities would return with the objects to exhibit them seeking to educate white Americans about the perceived traditional Native American culture. An important example of this process was artist George Catlin, who documented his findings mainly through his art and through the objects he stole from various tribal communities (Treier 2023, 78) . Similarly to Howard Chandler Christy, his artwork depicts the peaceful negotiations between Native American tribes and the United States government over the tribal lands. Oftentimes, artists such as Catlin were commissioned by the government to portray the events in this positive light to perpetuate the silence surrounding the horrific violence that was enacted on Native American tribes in the 19th century (Redmen 2021,127).

Catlin created a museum which he called his “Indian Gallery” to exhibit his artwork and cultural materials he extracted. The objects served as supplemental evidence to his artwork, seeking to convince the American public that his depictions were completely accurate and demonstrated an unmediated understanding of what Native American cultures were like. As many Americans across the country had not encountered many Native Americans took his material and artwork as fact, which furthered the stereotyping of Natives as his artwork typically exaggerated a dark red skin color and utilized stylized facial features (Treier 2023, 82). Furthermore, through careful study it has been suggested that Catlin fabricated the cultural material to better fit the depictions in his paintings. Therefore, similarly to Christy, the objects, especially garments, are better understood within the context of artistic props rather than true Native American objects without outside intervention (Treier 2023, 79).

Both artists contributed to the misinformation of the American public because the background of the expedition enabled the public to believe that the objects and artwork were being exhibited as they truly were. Yet, the artists intervened in many ways to shape the representation of Natives into one that further stereotyped them and separated them from the American mainstream culture as well as argue that they had peacefully relinquished their land. The primary goal of projects such as this was to save the artifacts from a traditional, by-gone culture which was being actively eradicated by the United States. Therefore, the moccasins are deeply representative of the salvage project in Native American communities, the extraction of materials as their people and heritage were being decimated, as well as the deceptive depiction of Native Americans culture in popular culture.

Treaty of Greenville.

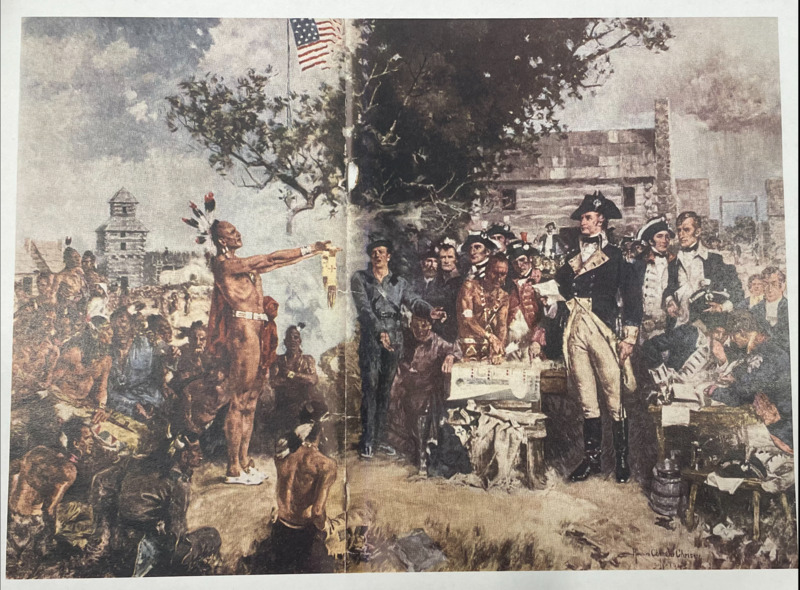

Treaty of Greenville, Howard Chandler Christy, 1945, Special Collections and College

Archives, Lafayette College, Easton, PA.

Native American Garments in the Howard Chandler Christy Papers

It is unknown how the Tsitsistas mocassins came into the collection of Howard Chandler Christy, but he utilized it as a prop, as it appears in several of his paintings and illustrations of Native American individuals. Not only are the moccasins a part of his collection, but he had a variety of garments in which he would use as costumes for the models he painted when making attempts at representing Native Americans. Despite the fact that he was depicting notable Native American figures, he would use these garments as props on white models in order to create his images. His disinterest in pictorial accuracy is evident in his work because his figures are either stylized depictions of Native Americans or simply appear to be white Americans dressed up as Native Americans.

Furthermore, studying the garments such as the moccasins it becomes increasingly evident as to the extent to historical accuracy was not integral to the artistic representation of Native Americans in Christy’s work. The moccasins appear in several of his pieces, yet the moccasins are not indicative of the true cultures of any of these individuals. Although the origins of the moccasins are unclear, comparing them to other known moccasins, it can be determined which tribe would have been responsible for the creation of these moccasins. There are a few factors which can lead to the determination of the origins of the moccasins. Most notably, the shape and cut of the shoe enable the understanding of its origin as Tsitsistas or Suhtai, which the American public generally refers to as Cheyenne. Another indication that provides this evidence is the white beading serving as a background for the blue and red geometric design.

One of the most clear examples of the Tsitsistas moccasins appears in one of his most recognized works, “The Treaty of Greenville” which hangs in the Ohio Statehouse as the largest painting in the collection. The figure at the center of the image is Little Turtle, the chief of the Miami tribe, who lived in present day Indiana. Moccasins from the Miami tribe would have had an extremely different appearance than the Tsitsistas moccasins in Christy’s collection. General features of Miami moccasins would have a more long and narrow shape with a wider cuff to the shoe; beaded designs were also much more commonly found in Tsitsistas cultural tradition. For both of these reasons, depicting Little Turtle in moccasins that are ornately decorated with a tall leather cuff is grossly inaccurate to what he would have truly worn.

Yet, the same Tsitsistas moccasins appear in yet another one of Christy’s illustrations with a fictional figure who was not intended to be from the Cheyenne Nation. In his artwork entitled “Hiawatha’s Wooing” he depicts the characters of Hiawatha and Minnehaha who were made popular through Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in his poem entitled The Song of Hiawatha. The poem itself is understood as a type of salvage project because it sought to preserve the mythologies of Native American tribes through the assumption that their culture was dying out. Yet, it simply perpetuated racist ideologies and stereotypes about Native Americans as Longfellow attempted to adapt the story for the reception of white audiences rather than staying true to the accurate story that was passed down through oral traditions. These characters are understood to be from the Dakota and Ojibwe tribes, respectively, which too would have had very distinct moccasins, very unlike the Tsitsistas model depicted in the image.

Although Christy’s “Pocahontas” is not shown wearing moccasins, analyzing the image furthers the idea that Christy was not interested in the accurate depiction of Native American individuals. His rendition of Pocahontas appears almost identical to his depiction of Minnehaha in “Hiawatha’s Wooing”, not just in their dress but in their facial features as well. Culturally, Minnehaha and Pocahontas would have been very unique, especially in their garments and traditional practices. Therefore, depicting them so similarly to the point where they seem as though they are the same woman, perpetuates the homogenization of white America's attempts to depict Native Americans and the incessant stereotyping in popular culture.

References

Hutchinson, Elizabeth. 2009. The Indian Craze: Primitivism, Modernism, and Transculturation in American Art, 1890–1915. N.p.: Duke University Press.

Redman, Samuel J. 2021. Prophets and Ghosts: The Story of Salvage Anthropology. N.p.: Harvard University Press.

Simpson, Audra. 2018. “Why White People Love Franz Boas; or, The Grammar of Indigenous Dispossession.” Indigenous Visions: Rediscovering the World of Franz Boas, (September).

Toulmin, Vanessa. 2011. “Preface: Empires 2. Colonialism and Display.” Early Popular Visual Culture 9 (4): 265–70. doi:10.1080/17460654.2011.641741.

Treier, Leonie. 2023. “Props and the Performance of Ethnographic Realism in George Catlin’s Indian Gallery: Fabrications in Hide, Paint, and Text.” Museum Anthropology 46 (2): 77–91. doi:10.1111/muan.12277.