The Legacy of Western Involvement in Iraqi Archeology

The legacy of colonialism in Iraq is a complex narrative where Western influence and colonial undertakings have played a central role in defining the commodification of the nation's cultural heritage, resulting in the exploitation and appropriation of its history and artifacts.

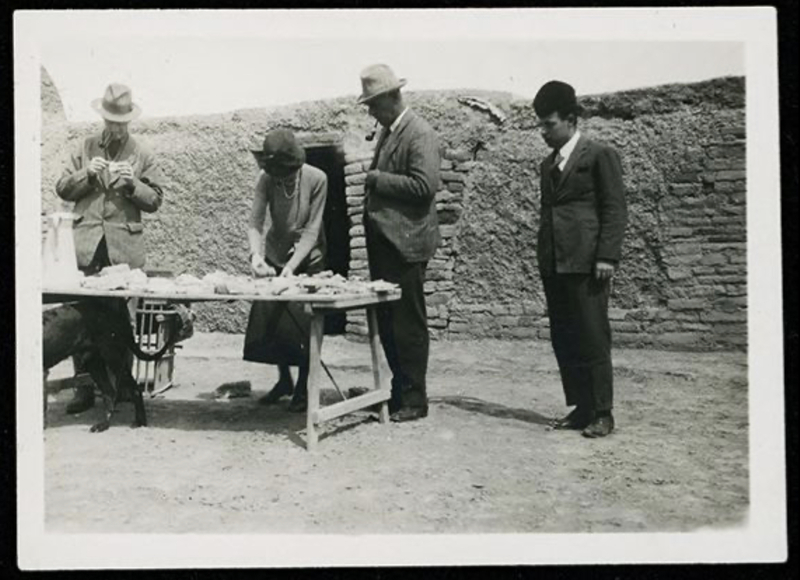

Gertrude Bell was the daughter of a well-off family. She received her education at Oxford and traveled extensively. Her pursuit of a life of exploration, academia, and diplomacy, paths rarely open to women during the early 20th century, defied convention. Bell, whether she had intended to be or not, was a trailblazer in her time and challenged the societal norms and expectations placed upon women (Ellis, 2004, 30). However, despite her accomplishments, Bell’s work was unambiguously in the service of a broader colonial agenda, one that subjugated the people and history she claimed to admire.

This colonial relationship held by Britain over Iraq was rooted in the geopolitical dynamics of a post-World War I world. Following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the League of Nations assigned mandates to oversee the administration of former Ottoman territories to certain Allied powers. In the case of Iraq, it was the British who secured the mandate, formalizing their influence in the region (Müller-Sommerfeld, 2016, 258). This mandate system was initially framed as a means to guide these territories towards self-determination and eventual independence (Müller-Sommerfeld, 2016, 260). However, in practice, the system built upon a savior mindset worked to uphold the interests of the colonial powers.

A white woman, unable to access a position of power in her home country, Bell moved herself down the perceived civilization chain to a country where her patrician heritage would give her the status and notability she so craved. Such a transplant is reminiscent of the trend of young, white Christian American women traveling to Africa. They arrive on the continent ready to play-pretend as doctors and nurses, hearts full of an unspoken desire to civilize the people they meet and to Western-ize their world because the Western way of doing things is empirically correct. Similarly, Bell saw the political turmoil present in the middle east and felt it was her duty to stabilize it, to build something proper and something British.

After years working in the region, Bell established the Iraq Museum and Iraqi Antiquities Service in 1922 (Gibson, 2008, 33). As the institution's first director, she oversaw the adoption of an antiquities law that allowed for foreign archeological expeditions to Iraq to legally retain some of the items they uncovered, dividing the items between their place of origin and the foreign powers who were given the privilege of digging them up.

By bringing a Western archeological lens to the region, Bell established a dangerous precedent. This lens would tell us that it is our duty to preserve the legacy of all the world’s cultures, but such a lens incentivizes the creation of a for-profit model of archaeological expedition. Western powers see the loss of the Iraq Museum and of notable archaeological sites as proof that the people of Iraq are not fit to manage their own materials, but such a view lacks the understanding that it was Western powers that created such a demand and such a profitable market for the stolen material in the first place, (Brodie, 2008, 49).

Lafayette College’s acquisition of its several Mesopotamian artifacts is representative of how complicit Western academic institutions have been in their participation in the antiquities market, willing customers for products of looting and extraction under colonial circumstances. Such complicit behavior creates a self-perpetuating system of artifact misappropriation, “creating an ever-growing market for antiquities and encouraging the looting. With no market, there would be no illegal digging,” (Gibson, 2006, 252).

For example, in 1997, Lafayette College purchased the clay cone on display in this exhibit, alongside a cuneiform tablet, from Ohio-based artifacts dealer Bruce Ferrini. The provenance of the cone between its excavation in Isin by the University of Munich and its presence in the inventory of Ferrini is not currently known.

Ferrini’s career, a middle man in the transfer of objects from their place of origin to their preservation in distant Western academic institutions, was one he held with pride. According to his website, during his career, “many hundreds of artifacts/items passed through his collection," ("Bruce Ferrini," 2023). His seasonal bulletins detail the selections for sale, a short paragraph is dedicated to each item’s contents, dimensions, and condition – all completely material information. Ferrini highlights the things that make each item unique, convincing his customers that each piece of ancient ephemera is something desirable to be owned.

Reference List

Brodie, Neil. “The Market Background to the April 2003 Plunder of the Iraq National Museum.” In The Destruction of Cultural Heritage in Iraq, edited by Peter G. Stone and Joanne Farchakh Bajjaly, 41-54. Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK: The Boydell Press, 2008.

Ellis, Kerry. “Queen of the Sands.” History Today, Jan. 2004

"Bruce Ferrini." Accessed Sept. 28, 2023. https://www.bruceferrini.com

Gibson, McGuire. “Archaeology and Nation-Building in Iraq,” review of Reclaiming a Plundered Past: Archaeology and Nation Building in Modern Iraq by Magnus T. Bernhardsson. Journal of the American Oriental Society, 2006.

Gibson, McGuire. “The Acquisition of Antiquities in Iraq, 19th Century to 2003, Legal and Illegal.” In The Destruction of Cultural Heritage in Iraq, edited by Peter G. Stone and Joanne Farchakh Bajjaly, 31-40. Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK: The Boydell Press, 2008.

Müller-Sommerfeld, H. “The League of Nations, A-Mandates and Minority Rights during the Mandate Period in Iraq (1920–1932).” In Modernity, Minority, and the Public Sphere: Jews and Christians in the Middle East, edited by S.R. Goldstein-Sabbah and H.L. Murre-van den Berg, 258–83. Brill, 2016. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctt1w8h27r.14.