The Imperial Postcard Collection: Japan and Its Colonies – Taiwan

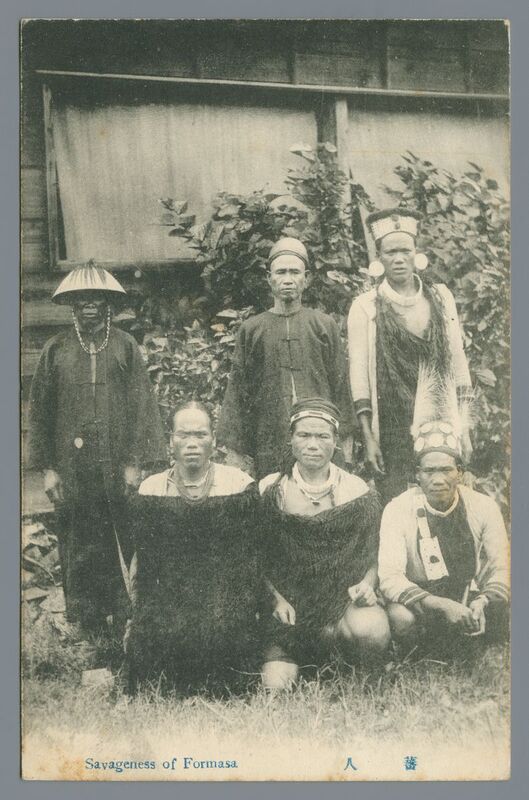

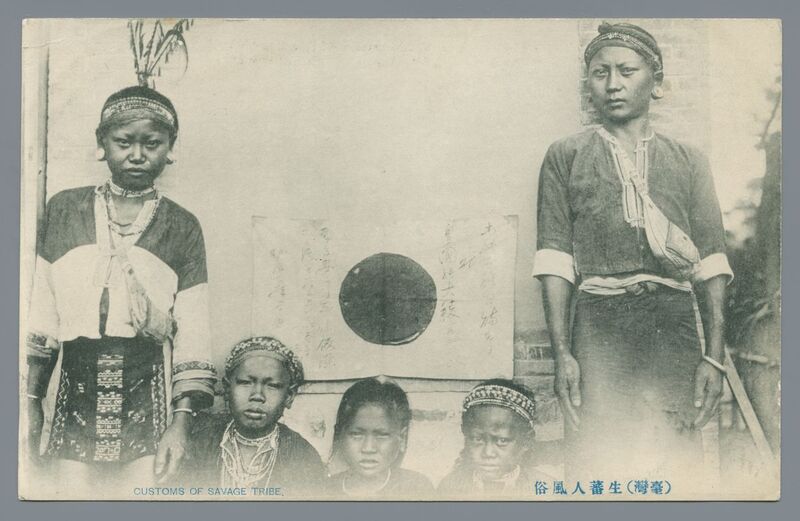

The word seiban (生蕃), literally translated as “unconquered savage” or “uncivilized aboriginal”, was a Japanese term frequently used during the mid-19th to mid-20th centuries, at the height of Japan’s colonial expansion. Seiban was used to describe Taiwanese aboriginals and other indigenous groups such as the Ainu, a group native to Northern Japan. To civilize the “savage” and conquer “untamed” lands demonstrates the attitudes of cultural superiority maintained by imperialist nations to establish foreignness between “primitive” and “developed” worlds. This objective of “progressive” interference was a legitimized basis for stripping indigenous cultures of their autonomy and lands, much akin to their Western counterparts with colonies in Africa, Southeast Asia, and throughout the Pacific (Xu Lu 2019; Eskildsen 2002).

Taiwan School for Aborigine Children – 台灣生蕃學童 Taiwan seiban gakudō “Taiwan Indigenous/Barbarian Schoolchildren”

Taiwan, February 14, 1933

Lafayette College Special Collections – Imperial Postcard Collection

This image of indigenous Taiwanese schoolchildren assembled outside a school building points towards Japanese efforts of “civilizing” (or “japanizing”) the Taiwanese population. A number of Japanese writers who visited Taiwan noted the distance that had to be maintained between the empire and its colonial subjects, such as not “excessively ‘japanizing’” the banjin (蕃人) so as to not make them so civilized that they threaten Japanese identity and superiority (Shimazu 2007). Other sentiments include a preference to experience a “yet-to-be-completed Taiwan” or an “incomplete Taiwan”, plainly referencing the land inhabited by the banjin or indigenous population, over an urban atmosphere (Shimazu 2007). This seemingly innocent fascination with the “wild” and “untamed” clearly fetishizes the indigenous Taiwanese as a foreign entity to the Japanese, permanently binding them to these descriptors.

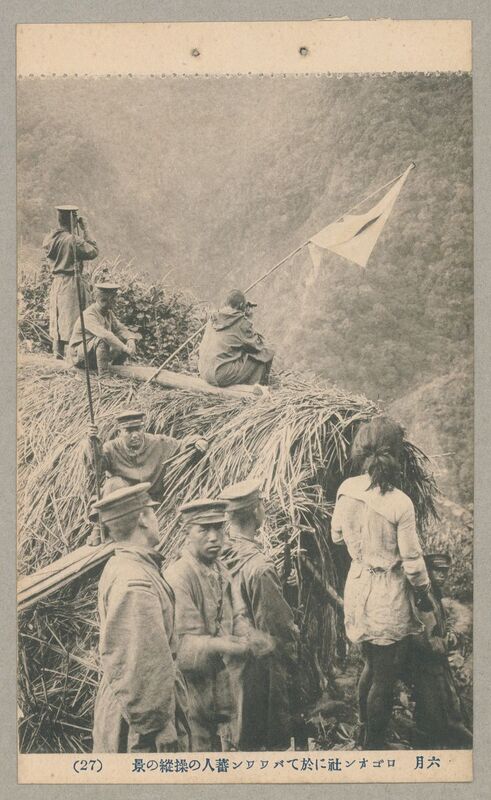

Utilizing a Bsawan Tribesman at Rogo'on Village – 六月 ロゴオン社に於てバワワン蕃人の操縱の景

Burning Down an Aborigine Dwelling at Skahing – 六月 サカヘン番屋の燒打

Printed by S. Kuwada & Sons. Osaka, Nakano Photography Studio, June 1914

Lafayette College Special Collections – Truku-Japanese War Commemorative Postcard Collection

Behind all the "modernization" that came, destruction immediately followed. This postcard set depicts the activities of Japanese troops during the Truku-Japanese War of 1914, whose ultimate goal was to disarm and assert dominance over the area controlled by the Truku people (today known as Hualien county) who were viewed as a threat to the Empire’s ability to control the entire island (Barclay 2018; Lafayette Digital Repository 2020). The first photo depicts Japanese soldiers in a village with an indigenous person in their presence, who most likely allied with the Japanese by forceful or voluntary means, while in the photo directly after shows a thick cloud of smoke, the result of the Japanese’s burning down of an aborigine dwelling. The stark contrast between these images highlights the ruthlessness of the Japanese Empire’s tactics to secure and mobilize their power over an indigenous peoples’ land, giving rise to the question of who the real “savages” are in this scenario.

It should be noted that the Japanese and Asian race as a whole were still regarded as being inferior by Western societies; the narrative of bringing progress from primitiveness and eradicating the “inferior” race (i.e., indigenous peoples) was heavily reiterated and promoted throughout the Japanese Empire to maintain its superior status on an international scale (Eskildsen 2002; Barclay 2018). Demonstrating their control and dominance over “uncivilized races” enabled the Japanese to expand and assert their role as a superior race comparable to their Western imperial counterparts (such as the United States, who during this time period, deliberately sought to exclude specifically the Chinese and Japanese) (Kenichi 2004; Takezawa 2014; Xu Lu, 2019).

Technological advancements, notably of photography and mass production, facilitated the commercialization of these distorted ideologies and interpretations of colonized peoples. Depictions of Taiwan’s indigenous communities and natural environment were naturally unfamiliar to urban city dwellers of Japan and other foreign (particularly Western) eyes; the desire to witness such exotic sights subsequently produced a fetishised touristic allure that only reinforced the imperial objective (Shimazu 2007; Liao 2007). For visiting foreigners, these postcards were viewed merely as souvenirs, a small piece of information that represented a whole; for the Japanese empire, they were an opportunity to libel the Taiwanese population and exhibit their standing as an international power (Barclay 2010).

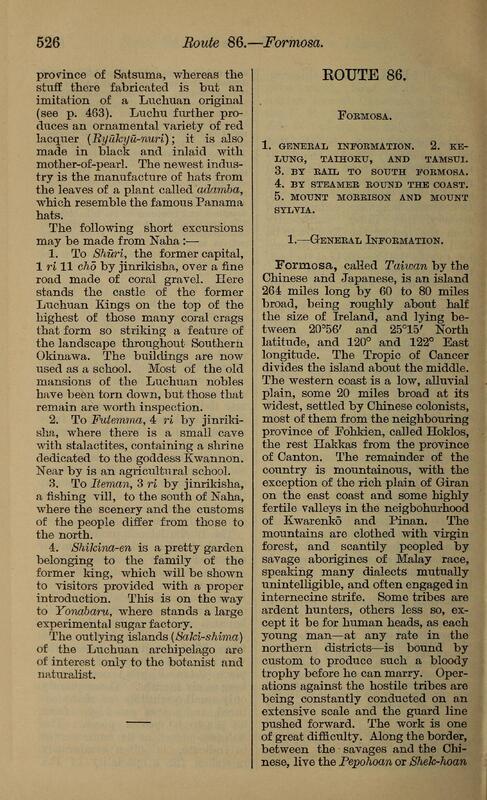

A Handbook for Travellers in Japan (Including Formosa)

Basil Hall Chamberlain and W. B. Mason, New York, Charles Scribner's Sons, 1913.

This American traveler’s handbook of Japan 1913 describes that Taiwan’s landscape and mountains “are clothed with virgin forest, and scantily peopled by savage aborigines of Malay race, speaking many dialects mutually unintelligible, and often engaged in internecine strife” (Basil Hall Chamberlain and W. B. Mason 1913, 526). The map displays Taiwan as being part of Japan.

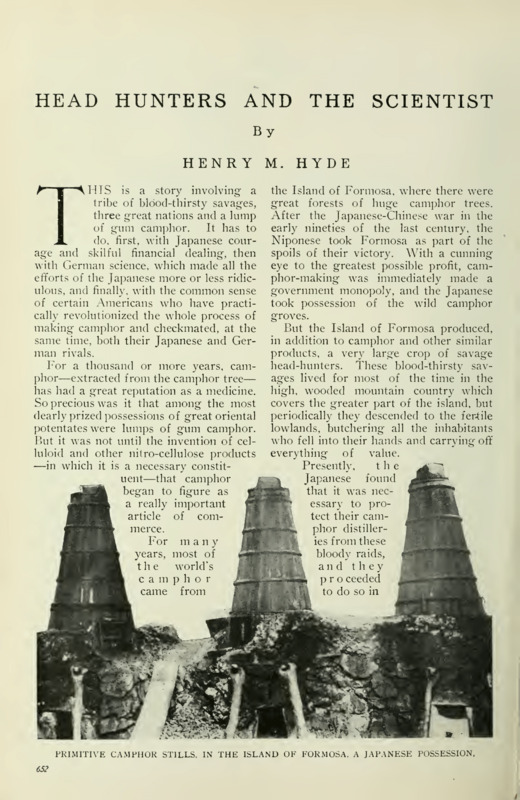

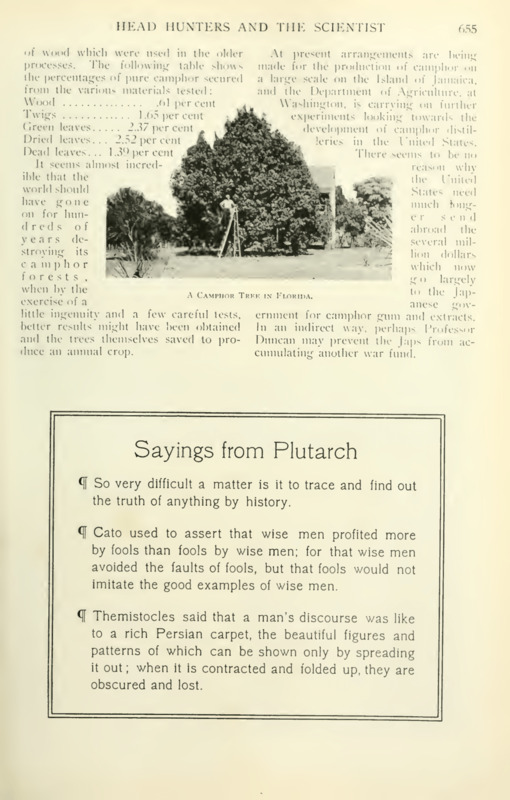

"Head Hunters and the Scientist"

Henry M. Hyde, Technical World Magazine, Vol. XVII, No. 6, Chicago, August 1912.

Henry M. Hyde, an editor and writer for the Technical World Magazine from the early 20th century, describes the Indigenous Taiwanese as “bloodthirsty savages” who lived mostly “in the high, wooded mountain country [...] but periodically they descended into the fertile lowlands, butchering all the inhabitants who fell into their hands” (Hyde 1912, 652).

Trademark registration for Savage Maid brand Formosa Oolong Teas

T. T. Barr & Co., June 26, 1883

This logo for an American coffee and tea brand, Savage Maid, depicts a stereotypically dressed and tattooed indigenous Taiwanese person. Though it was created before the Japanese took control over Taiwan (1895), such an illustration inherently demonstrates existing conventions about native peoples as a whole.

Choice language helped reinforce the foreignness of indigenous populations– by consistently associating words with negative connotations such as “savage” or “wild”, the writer inherently suggests that their own culture (and ones similar to theirs) are the opposite. This produces two worlds of “right” and “wrong” (i.e., “civilized” and “uncivilized”) that an empire uses to justify their existence and to eliminate and/or forcefully subjugate the “untamed”.