"The Hostess:" A Woman's Image in Coffee Ads, 1920-1950

Below is a passage taken from “The Advertising Handbook” written in the 1920s, on what advertising is and how it functions in America. The excerpt features the author's thoughts on the role of men and women in society.

Man is the stronger, as a rule. He is the breadwinner, to a large extent. His job is more in the outside world. He grows up to severer tasks, as a rule. He is more accustomed to rebuffs.

Though woman has progressed a long way in taking her place on an equal plane with that of a man in business, politics, and the professions, yet she is still to a large extent more sheltered than man. Her affairs are more within the home. Her sex makes her interest in clothes, home-furnishings, and the like keener than man's, as a general thing. (Hall, 101)

This excerpt provides context on how genders were perceived in the 1920s. It is a window into the perceptions of some people during this time, and provides support to the idea that it was indeed an era rooted in many forms of sexism. According to the author, the characters shown in these types of ads, are true to what was believed of men and women of this time period. The roles of husbands and wives were normalized into gender stereotypes that clearly portrayed women as subservient to men.

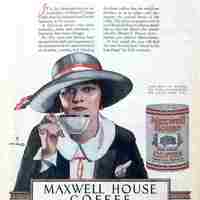

When viewing the Maxwell House print advertisement from 1923 (on the left), the observer will begin by reading the text at the top: “It is the day-in-and-day-out dependability of Maxwell House Coffee that has endeared itself to the hostesses of the nation.” This opening sentence successfully captures the word choices and images I’m pinpointing as supporting the stereotyped figure of women in coffee advertising. The word “hostess” refers to the wives of households, who usually assume the role of welcoming and serving guests who are invited into the home. It is this act of serving others in the home, that led to the image of a wife, or “hostess,” being paired with beverages like coffee. Sociologist Thorstein Veblen describes the expectations of a “well-bred housewife [is to] perform certain offices and show a servile disposition” (Davis, 108). For instance, the second image above isn't a traditional advertisement by Maxwell House Coffee, but instead a pamphlet including recipes with their product. The recipes include how to make a proper cup of coffee or tea. The fact that the image used on the front of this pamphlet is a woman sitting with cups and pot of coffee, supports the idea that it is the expected job of the woman to read this pamphlet and to know how to prepare and then serve these beverages. Furthermore, author Katherine Parkin writes that “one way that food advertisers sought to sell their products was to encourage women to identity with the role of homemaker” (Parkin, 5). In this way, advertisements have the power of increasing consumption of their products by simply implying they are necessary for a certain “role” one has in society. Since women have been given this role of the housewife for such a long time, women are therefore targeted more frequently in ads for domestic items and food. Simone Weil Davis summed this up well when she wrote that the products a woman buys ultimately assemble and portray her identity (Davis, 2). Her identity is in part shaped by the things she shops for, and what she shops for is shaped by the ads she views in everyday life.

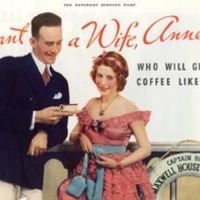

Maxwell House ads also provide ample material for observing the represented relationship between a husband and wife. In the advertisement from 1943, you will find the two larger illustrations portraying a husband and wife. In the upper right hand corner, the wife holds a buzzing alarm clock over the husbands head and pulls off his blanket; presumably waking him up. The illustration below shows the husband holding up a steaming cup of coffee and smiling. The wife is in the background looking back at him, and holding the coffee pot. The sequence of events of the wife waking the husband and then serving him coffee contributes to the idea that a woman’s household occupation job in the household is a caretaker and servant. The husband is in a suit and it can be assumed that he will be leaving to go to his job for the day. The wife in this particular depiction seems to be put below the status of the husband, in that her duties are to wake him and serve him before he goes to work. Presumably she remains contained in the home environment and by household responsibilities. Again, coffee advertisements often target women by displaying women in these domestic scenarios, where it emphasizes their duties to their husbands. Author Mark Pendergrast describes these types of coffee advertisements as “appealing to the sexism of the era, convincing women that their social status and marriage depended on using the correct brand of coffee, facial cream, or cooking oil” (Pendergast, 130). Advertising companies emphasize the expectations placed on these women, and utilize the depiction of the wife and husband to convince their consumers what they should be buying, to fulfill a woman’s duty as an “American housewife.” The advertisement from 1943 that shows a man and woman, well dressed and on a boat, portrays these particular expectations well. The caption of the ad reads: “I want a wife, Annette, who will give me coffee like this!” This Maxwell House ad is essentially broadcasting the message that it is expected of a woman to marry a man and then spend her time serving her husband, thereby accepting a lower status in society and in the home.