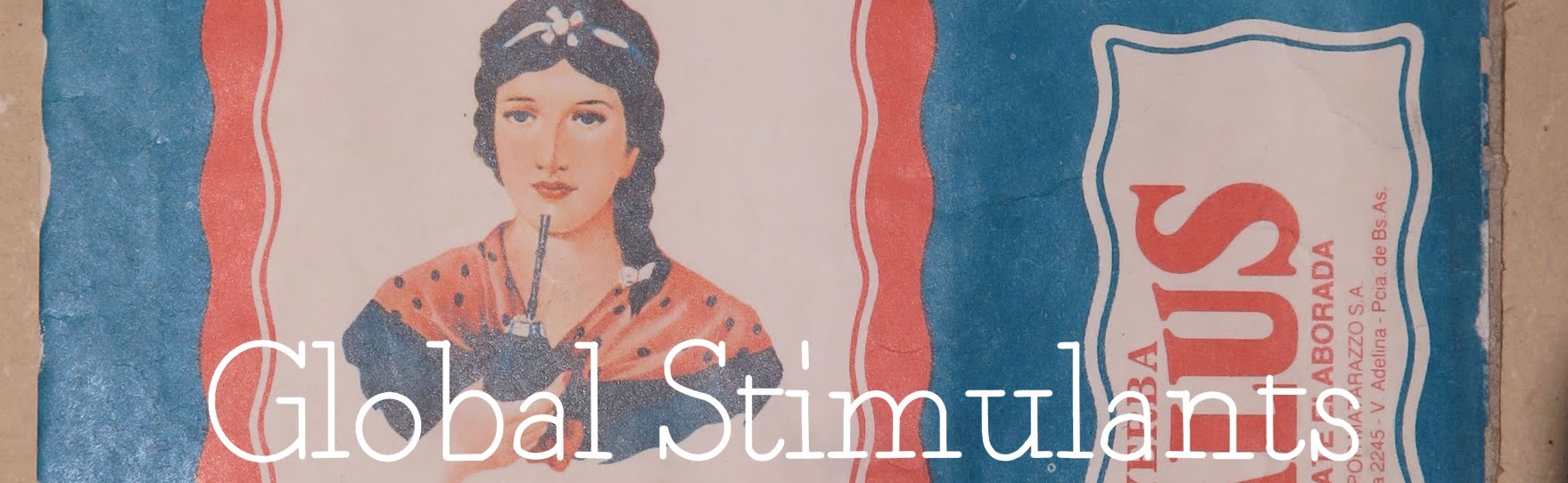

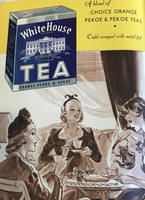

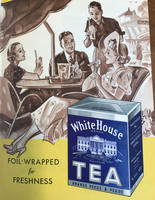

Mrs. Tea: The Feminization and Shaping of Gender Roles Through Tea Promotional Materials From the 1900s-1950s

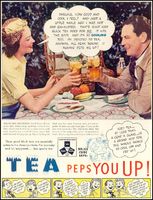

"Copywriters throughout the [20th] century embraced a fundamental theme: regardless of the actual work involved, women should serve food to demonstrate their love for their families. Countless ads reminded women that food conveyed their affections and fulfillment of duty to their families. In the hands of women, food is love.”

Katherine J. Parkin, Food is Love: Advertising and Gender Roles in Modern America

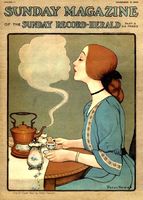

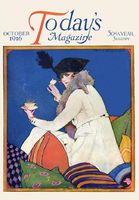

Advertisements serve as a lens from which historians can examine societal values, as the images and language they use give insight on how the advertisers viewed certain groups of people. During the 20th century, women were the main target of food advertisements because, as Parkin states in the quote above, they were expected to show their love through food and drink. This exhibit features American tea promotional material, including advertisements and magazine covers, from the first half of the 20th century and focuses on answering this question: how did these materials perpetuate the feminization of tea and shape gender roles at different points in history? Our analysis is broken up by decade, starting with the 1900s and working our way to the 1950s. We intend to show how, while the aesthetics of the promotional material change, the overall message of women being regulated to domestic roles remains constant throughout.

The origins of tea in America begin in the colonial period, where tea was popular among people of all classes. When Britain implemented legislation like the Townshend Acts and the Tea Act that placed a tax on the beverage public opinion quickly changed, and drinking tea was seen as unpatriotic (Saberi 82). Once the Revolutionary War was fought and eventually won tea drinking was no longer a political statement and thus the drink started to gain popularity (Saberi 82). During the 19th-century, tea recipes started appearing in cookbooks and the drink began appearing in menus across the nation (Saberi 95).

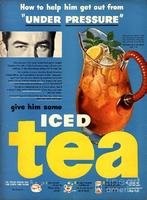

The turning point in American tea consumption came in 1904 at the World’s Fair in St. Louis. Saberi discusses the story of how Richard Blechynden, the director of the East India Pavillon, tried giving out free Indian tea to fair-goers, but due to the heat, no one took the samples (95). He and his team then proceeded to pour the hot tea down iced lead pipes to cool the beverage, which the fair-goers then began to drink (Saberi 95). This was not the first time “iced tea” was invented, as there is evidence of iced recipes in cookbooks from the late 19th century, but this was the beginning of its popularization and commercialization.

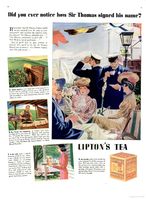

The gendering of tea has its roots in British tea gardens. These spaces “were particularly popular with women” as they allowed them to enter the public sphere; the consequence of this, however, was that tea became synonymous with women (Standage 195). Many British tea companies -including Lipton which is highlighted in this exhibit- advertised in America, which meant that the gender roles established in Britain traveled across the ocean. Piya Chatterjee states that this was seen as a hindrance “to [tea’s] potential as a popular drink in the United States,” and with coffee being introduced as a more masculine beverage tea was solidified as a primarily women’s drink. Consider the role of agency in this narrative: it was men who decided that tea would be a female beverage based on their heterosexist ideas of masculinity, and in turn, they defined femininity without the input of the women affected by it.

American advertisers had no trouble capitalizing on this femininization, as they were already focusing their resources on marketing to women consumers. In the 1930s a study conducted by the J. Walter Thompson agency “asserted that 85 percent of all advertised products were bought by women,” so it was simple to incorporate tea into already feminine advertisements (Hill 8). The historical context of each decade played into how advertisers chose to portray these gender roles, whether it be using the image of a “modern woman” in the 20s or promoting traditional family values in the 50s. These images and ideas defined the type of women who drank tea, which remained a middle to upper-class white woman who was married or otherwise heterosexual. These intersections of gender, class, race, and sexuality are what shaped the gender roles in American society and played into the larger narrative of tea and tea consumption. Tea was historically marked as a femininized beverage, but advertisers took this image and used it to change society in order to sell their product.

Credits

Julia Cassidy and Emma Krasinski