Naturalizing Modernity: The Rural Imaginary in Twentieth Century Yerba Mate Advertisements

By Stefano Mancini

Think about the last time you were in a place that you might call nature. Maybe it was a city park, or on a hike, or maybe you can even turn around right now and look outside a window to see nature. Perhaps you felt serene and at peace - like you had escaped from the hustle and bustle, and were in a place untouched by humans.

But is nature really untouched? What is nature, anyway? And why does whatever we call nature feel so freeing from the constraints of everyday life? These questions might seem high and philosophical, and in some sense they are; but on the other hand, their answers are instructive for the ways that we interact with the world around us and, just as importantly, the many groups and peoples that live in it.

These questions, in fact, provide a useful lodestar as we immerse ourselves to the crowded streets of early twentieth century Buenos Aires, Argentina, where you might hear many languages walking down a calle, see bright colored houses of recently arrived immigrants, and, importantly for our analysis here, taste a yerba mate, a classic caffeinated Argentinian drink made from the leaves of a holly tree which grows in some inland areas of South America, including Paraguay, Brazil, and Argentina (Folch, 6).

Yerba mate’s long history can illustrate and illuminate other histories to us. Indigenous people, for instance, consumed yerba before colonization in the sixteenth century, and Spanish Jesuits who took control of what is now Argentina forced Indigenous laborers to work on their yerba plantations as part of their project of exerting political and religious control over the territory and its people. Anthropologists like Christine Folch, then, have used yerba mate to understand how the Spanish exerted control over the people and land of South America in the early modern period.

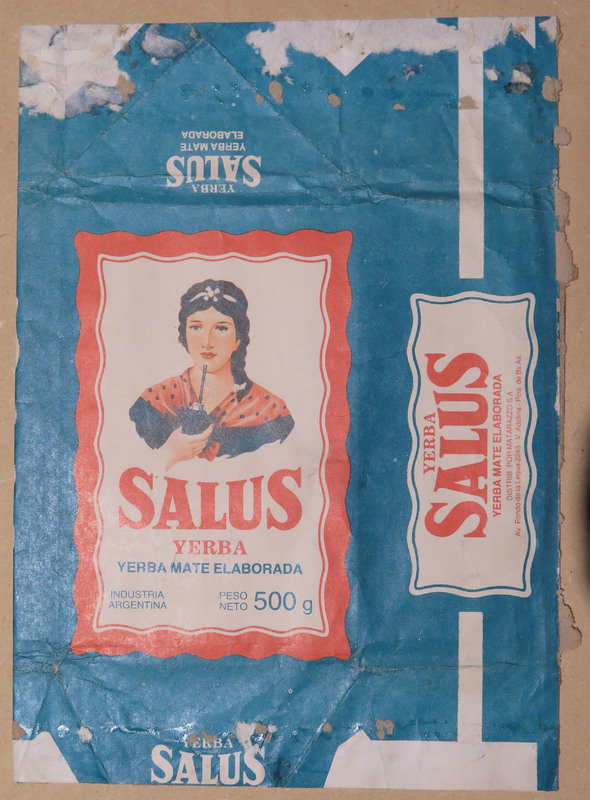

In the two centuries after the period that Folch studied, the nation had gained independence, military forces had “conquered” the Indigenous people (although to assume that their conquest was fully successful would flatter the colonizer), and, starting in the late nineteenth century, immigrants came from Europe and faced discrimination upon their arrival (Pite, 4-5). Nevertheless, mate’s importance and contested nature in Argentine society, identity, and self-fashioning endured. Some European commentators scorned mate, associating the indigenous history of the drink and the convivial ritual of sharing a mate as uncivilized and unsanitary (Dohrenwend, 17). In her study of practices in postcolonial twentieth century Argentina, Rebekah Pite uses images of mate to understand how Argentines conceptualized gender, labor, and their own identity, and defined the nation as heterosexual and patriarchal. Who produces yerba mate and who drinks (or is imagined to drink) yerba mate, evidently, are fertile terrain for inquiry. Here, I seek to join in that discussion, and consider how yerba mate advertisers marketed their products in the first half of the twentieth century, as companies distinguished their packaged yerba.

Advertisements from yerba mate producers, who sold packaged yerba to consumers, were particularly interested in the meaning of nature. Rebekah Pite compiled these advertisements from Caras y Caretas, a national but particularly urban magazine that facilitated the development of a middle-class, European-like identity among readers (Rebaza-Soraluz, 430). Advertisers utilized rural visions to lay claims to the purity of their yerba and negotiated the contradictions and complications of modern life through portrayals of rural life and its relation to mate. Throughout the first half of the twentieth century, advertisers equated yerba as a panacea for the social ills of modernity and as a romantic embrace of argentinidad. Over the twentieth century, ads focused less on the archetypal “people” - gauchos and indigenous people - of rural landscapes, increasingly promoting a vision of Misiones and other yerba-producing regions as pure nature.