Cultivating Nature: "Pure Nature" and Yerba Production

Over the first half of the twentieth century, advertisers shifted the focus of their gaze from the Pampas to the selva; from the grassy imagined home of the gaucho to the dense jungles of provinces like Misiones that were the real home of mass yerba production. The ideas of yerba's jungle origins already existed as an option for advertisers - see the La Hoja advertisement as the last page - but advertisers began to use this image as the overwhelming origin story of yerba in the mid-twentieth century.This shift was not accidental, or even simply a benign portrayal of yerba. Instead, advertisers deployed long-standing ideas about "pure nature" that colonizers, creoles, and Euroamericans alike crafted to interpret South America in order to bolster a brand's claim to pure and authentic yerba that was a marker of elite Argentine status.

“Pure nature” is not my own term, but comes from Mary Louise Pratt’s research on the writings of European naturalist and adventurer Alexander von Humboldt, a celebrity in his time. Von Humboldt visited the Spanish colonies in the Americas around the turn of the nineteenth century, visiting a region on the precipice of political independence due to the agitation of colonial elites (Pratt, 112-116). With his descriptions of South America’s natural grandeur, he, according to Pratt, taught Europeans that the Americas were ripe for colonization, with no society or history, a rugged and wild place to be tamed (Pratt, 123). It is this same envisioning of South America as wilderness, which was so present in the minds of early modern Europeans, that Argentinean advertisers appropriated in service of the sale of mate.

As we saw in the last section, early twentieth century advertisements focused on mate’s association with the peoples of rural life. But here, advertisers instead focused on the primeval vision of inland South America to advertise the purity of their mate. Although producers might have cultivated massive yerbales, advertisers taught consumers that the industrialized and packaged mate of the city was a pure, rural product nonetheless. These tropes, nonetheless, particularly distanced themselves from framing mate as so untamed as to be unsanitary; instead, the conquering of pure nature through cultivation led to a clean, healthy mate.

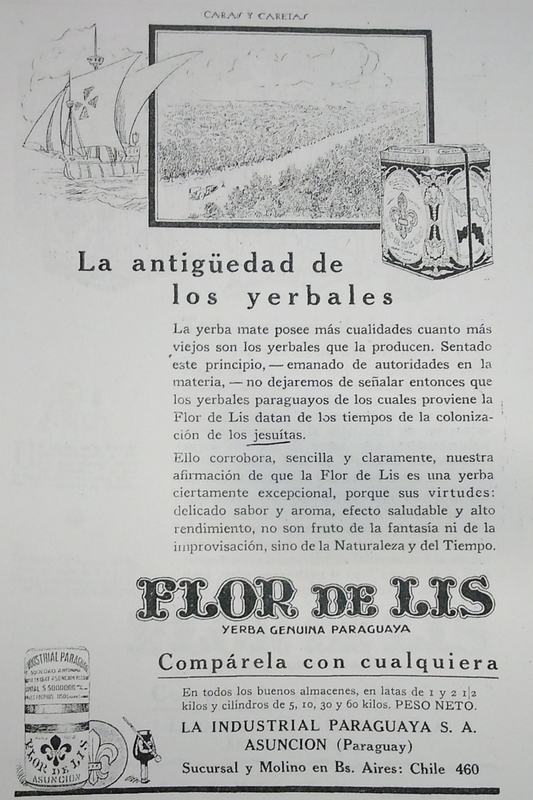

Flor de Lis, as we saw on the last page, populated the rural imaginary with a variety of figures who could attest to the quality of their Paraguayan yerba. But Flor de Lis was not shy about also using visions of pure nature to advertise their mate as the mid-twentieth century approached. In 1927, they released this advertisement, in which the age of the yerbales became a defining feature of a quality mate. The dating of the Flor de Lis plantations from the time of the Jesuit arrival (represented in the image by a caravel) allegedly meant that Flor de Lis was a superior yerba, both due to the "delicate flavor and aroma" and the benefits to the consumer's health. They invited bourgeois consumers, then, to demonstrate their good taste through purchasing Flor de Lis. Though the text focused on cultivated mate, the image on the advertisement displayed a boat sailing through a vast, wild nature, and attributed the power of Flor de Lis to "Nature and to Time." Thus, the timeless eternity of grand nature indicated good quality; the advertisement hid the people who cultivated the yerba and the transformation of land to yerbales.

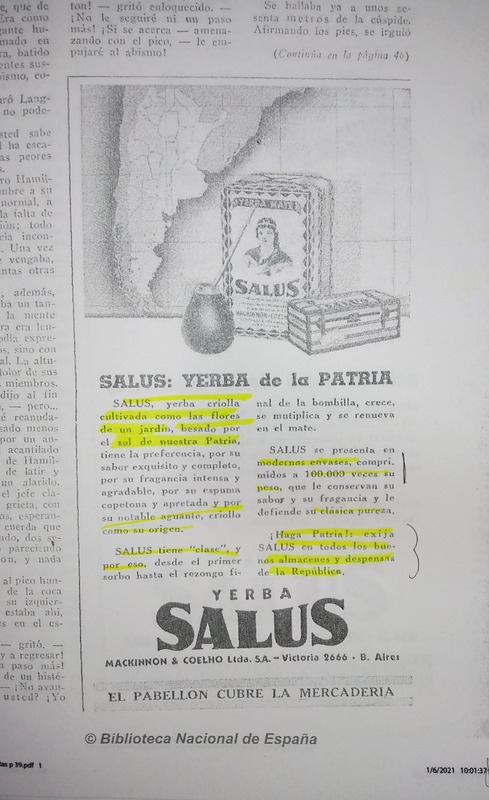

This 1936 advertisement, by Salus, too straddles the border between nature and cultivation. In the rhetorical imaginary of Argentinean advertisers, an untamed nature would represent the triumph of the primeval, while a fixation on cultivation would threaten the purity of the mate. Unlike Flor de Lis, however, a major selling point of Salus was that the yerba came from Argentine territory. To support Argentina, one should buy Salus and take advantage of the quintessential purity that only an Argentine yerba mate could provide. Ideas about race and nationalism are hypervisible in this advertisement even as Salus erased people from the rural landscape. They claim that their yerba is criolla, a historically racialized term to refer to people of European descent born in the colonies. By the early twentieth century, criollo/a was a catch-all term in the lexicon of elite Argentines to refer to local products or practices, as they defended their own status as the preserver of Argentine tradition against the incoming immigrant population (Pite 2016, 101). To consume Salus yerba was not just patriotic, then, but a setting of the boundaries of argentinidad against new immigrants. Advertisers blended language and image to put together a cohesive message: that Salus' yerba was as pure as the Argentines who drank it. Argentina's pure nature, in the view of Salus, was a contrast to the urbanized and modern city where immigrants would mingle with elite white Argentines.

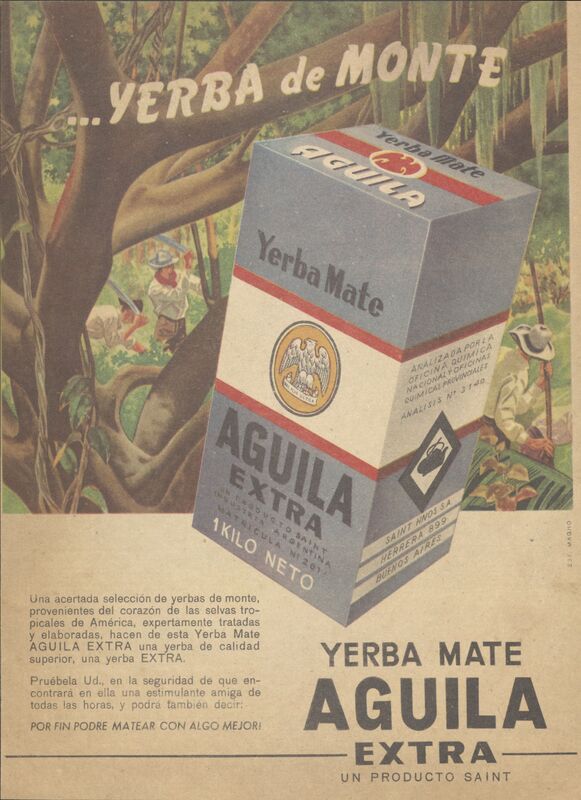

By the 1950s, advertising in Argentina had changed significantly. In the early days of Juan Domingo Peron’s presidency, the common worker, for the first time in rhetoric, became both a subject of and a participant in the Argentine political system (Milanesio, 87). Despite the broader changes in advertisement, however, mate advertisements did not necessarily change in their thematic content. Instead, they continued to harken to pure nature as a marker of good quality. Aguila’s 1950s advertising campaign claimed that mate was both from the “jungle” and the “mountain,” and both images here lack people except for apparent colonizers in the “Yerba de Monte'' advertisement. These men, with pale skin and dressed like gauchos, tame the alleged wilderness of pure nature; they are small, insignificant, and hidden compared to the vast grandeur of the timeless forest. Yerba, in modern plantation production, clearly does not spring naturally from the ground; although there may be influence, in this colorful and more whimsical rendering of yerba as pure nature, from the populist advertising of the Peronist era, Aguila made little change to the dominant trends of early- to mid-twentieth century advertisements.