Purifying Commerce: Caricatures of Indigenous People

Gauchos ruled the countryside in the Argentine imaginary only because of the literal disposession of the indigenous people, or indios, that inhabited what became Argentina, after centuries of fighting. Marketers, however, brought indigenous people to the center of the Argentine imaginary to advertise yerba. Indigneous people were the first to take yerba, the basis of all later Argentine consumption, and the mate ritual was a sign of Argentine distinctiveness. The definition of indigenous people as primitive, which already existed in the minds of many Argentines, helped brands demonstrate that their yerba was particularly pure. But, according to marketers, did drinking mate, then, make Argentines primitive? Here, I will consider the negotiations that marketers made to answer - or, more accurately, carefully thread around - that question.

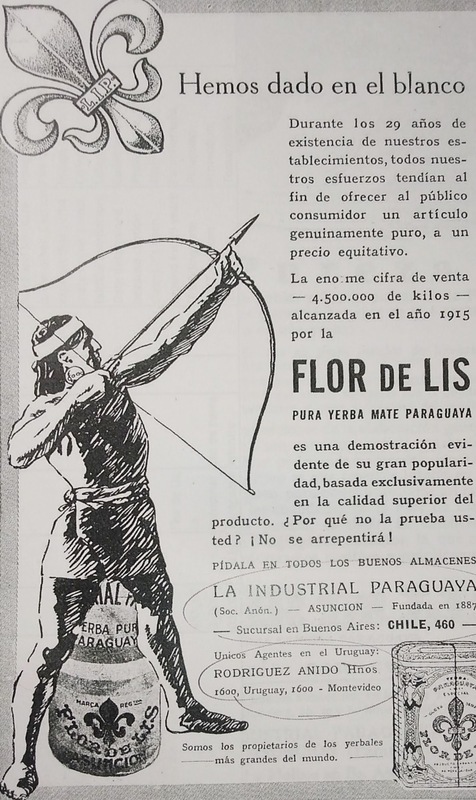

In 1916, the Flor de Lis corporation advertised their mate using a typified indigenous person holding an outstretched bow and arrow to discuss the quality of their mate. The advertisement claims that Flor de Lis has “hit the target,” just like the skilled and dexterous archer in the advertisement, with their quality mate.

Past the wordplay, the use of indigenous people was not accidental on the part of Flor de Lis. Argentine national identity in the twentieth century looked towards Europe for inspiration; the arrival of Spaniards nearly four centuries ago, according to the mythology, made Argentina a civilized and, in particular, white nation (Chamosa, 54). At the same time, turn-of-the-century elite Argentines looked towards the provinces (often as tourists) to see indigenous people as subalterns who, while integrated within the nation, were evidence of the modern superiority of the urban white elite. It is this discourse, which Chamosa calls “romantic nationalism” as opposed to cosmopolitanism, that Flor de Lis harkened to in order to advertise their yerba. What is most interesting here, however, is that Flor de Lis sold Paraguayan yerba. Flor de Lis, then, made no nationalist appeal, but nevertheless appropriated the trope of indigenous people as primitive to show that their mate was pure.

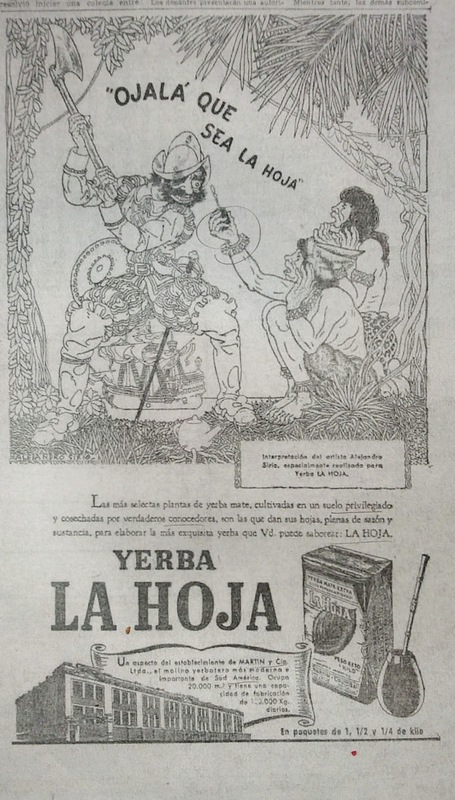

In 1944, La Hoja released this ad that bordered on the absurd, showing caricatures of indigenous people serving a mate to a colonizing Spaniard. They sit in a dense and lush jungle, what might be the imagined home of the loincloth-wearing natives who play the role of primitive in this ad’s worldview. The colonizer, meanwhile, wears jewelry bordering on the ostentatious, sits on a miniature caravel, and wields an axe that he presumably used to chop down trees in this jungle. His greedy gaze looks towards the mate with desire for the native product, menacingly “hoping that it is La Hoja,” while the indigenous group submits in their handing over of the drink. Here, La Hoja became a treasure as valuable as the silver the Spanish extracted at Potosi. Consumers, too, could participate in this culinary colonialism through buying mate from La Hoja; indigeneity was a mark of a genuine cup of mate, of “exquisite” yerba no matter where it came from or who picked it in reality.

Both depictions of gauchos and indigenous people, then, were tropes for advertisers to demonstrate to consumers that mass-produced and packaged mate was still pure. Under a backdrop of modernizing Argentina, I argue that these advertisements eschewed cosmopolitanism and played into a wider discourse that Jeane Delaney notes was many Argentine elites' projects of defining themselves as "defenders of the true Argentina" (Delaney, 459). Even companies that sold Paraguayan yerba could join this shared discourse, though - to become a modern Argentine, according to producers with plantations in Paraguay, did not require the drinking of Argentine yerba. Over the next few decades, however, stereotypical depictions waned in popularity in favor of depictions of rural areas without people.