Occupying the Imaginary: Representations of Gauchos

What comes to mind when you think of Argentina? For some, it might be a somber tango or a sentimental tango dance. For me, a foodie, I think of tender beef with a pungent chimichurri (and, of course, the obligatory person at your table who reminds you that cilantro tastes like soap to them - a tragedy, if I do say so). And for others, one might think of the topic of part of this discussion, the gaucho, the masculine rural rancher responsible for that cut of beef that I love to take with that spicy, vinegary sauce.

The road to symbol, however, is rarely straight and always full of obstacles along the way. National symbols include and exclude - they define the nation or group as a person, place, or thing, privileging certain identities and marginalizing others. Every symbol has a story as to how it became a symbol, and once it became a symbol, people used it in service for certain ideologies, social movements, or assertions of privilege.

Twentieth-century Argentina was no different. Here, we will explore the national figure of Argentina, the gaucho, and another group associated with rural Argentina, indigenous people. We will trace how urban advertisers used rural people to frame how people thought about mate and, along the way, consider the histories of how the gaucho and the indigenous person became effective tools for advertisers to wield.

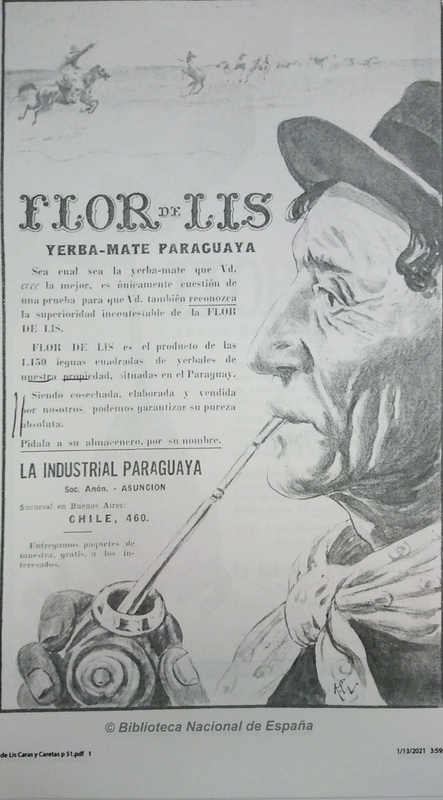

Cometh the hour, cometh the man - we will start here in 1913 with a Flor de Lis advertisement in which an elderly gaucho sips a mate while other gauchos ride horses on the Pampas behind him. The man seems dignified and almost heroic, yet the act he performs is simple. Here, the gaucho gave authority to the purported quality of Flor de Lis. No matter “what mate you believe is the best,” the ad claims, Flor de Lis’ promise is that their mate is in fact the highest quality. What was, exactly, the mark of quality? Well, it was “unquestionable” that their Paraguayan mate was, in fact, the best; perhaps the face of the gaucho was an endorsement. Many Argentines, in fact, did view Paraguayan yerba as first-rate (Folch, 16). Urban Argentines did not always love the gaucho; in the nineteenth century, liberal nationalists scorned the gaucho as a rural, uneducated bumpkin. But by the twentieth century, as Argentina imported European workers, incorporated new technologies and modes of speculative accumulation into its economy, and urbanized, the gaucho became a national hero for liberal elites, an embodiment of Argentine purity in opposition to the racialized immigrant and the "impersonal forces" of modernity (Delaney, 435). The choice to drink South American mate itself, in fact, would have been a significant form of protest against cosmopolitanism (Delaney, 439). In the equation between Argentine identity, purity, and the gaucho, then, the image of a gaucho would suggest a clean, classic, and authentic mate. Fear of immigrants in modernizing Buenos Aires, then, made an Argentinean mate pure.

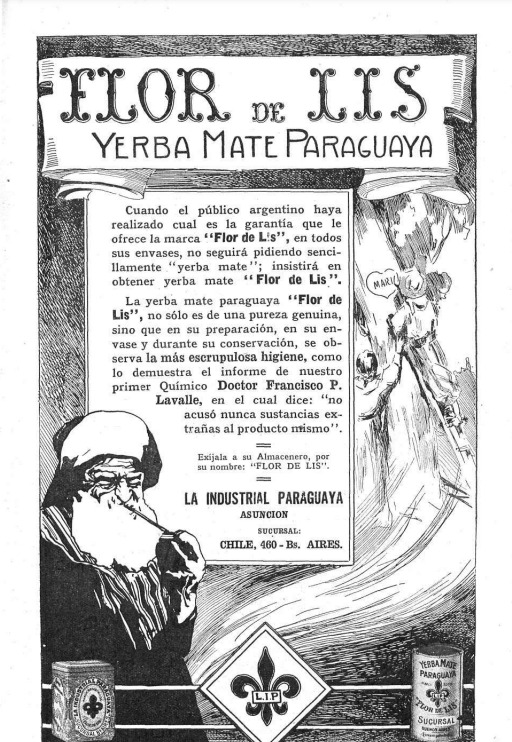

The natural purity of the gaucho, in some sense, stood apart from the scientific and civilized purity of the city. In this advertisement, also from Flor de Lis in 1913, a gaucho drinks from a bombilla; notably, he is alone, meaning he is not participating in the communal ritual of mate. The advertisement features an alleged endorsement from Doctor Francisco P. Lavalle, who claimed that Flor de Lis' yerba was sanitary at all points in the growing and boxing process. Thus, both city and country came together in this advertisement to suggest that Flor de Lis was an authentic and pure mate that nevertheless was "hygienic" through the urban practices of modern science.

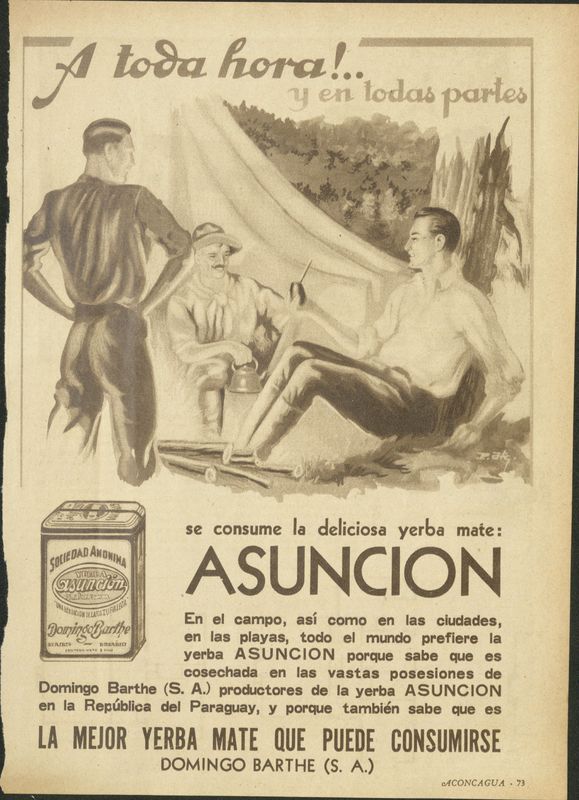

Gauchos, in the renderings of advertisers, were not necessarily totally spatially cut off from the rest of Argentina. In this advertisement from 1932, in which Asuncion reminds their readers that people “at all times and in all places” enjoy their mate, a gaucho pours water into the mates of well-dressed, urban, bourgeois men. Together, they are at a makeshift campsite in a wild country area, with a few logs at their feet indicating that they will set a fire. This blend of the rural and the urban supported Asuncion’s larger assertion here - that no matter where one is in Argentina, they could enjoy a long-lasting, quality Paraguayan mate, and that consumers, no matter where they live, always look for Asuncion. This blending, however, might also complement other embedded ideas about mate. With bourgeois men enjoying it in the countryside, they might bring their cosmopolitan civilization to the imagined backwards rural space. The presence of men at all indicates that the advertisers hoped consumers imagined rural areas as a space which they could use for leisure, in which the gaucho would serve them.