1920s: Flappers and Fundamentalists

The 1920s saw a major post-war economic boom, which led the public to engage in consumerism more than ever before. All classes were encouraged to participate in extravagant spending through installment plans and credit, many of these being household machines such as washing machines and stoves (Reeves 85). The result of this for women was that the chores done at home could be done faster than ever before, allowing them to have free time to further engage in consumerism (Reeves 85). The continued work of suffragists led to the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920 which gave women the right to vote, bringing in a new era of political activism (Reeves 86).

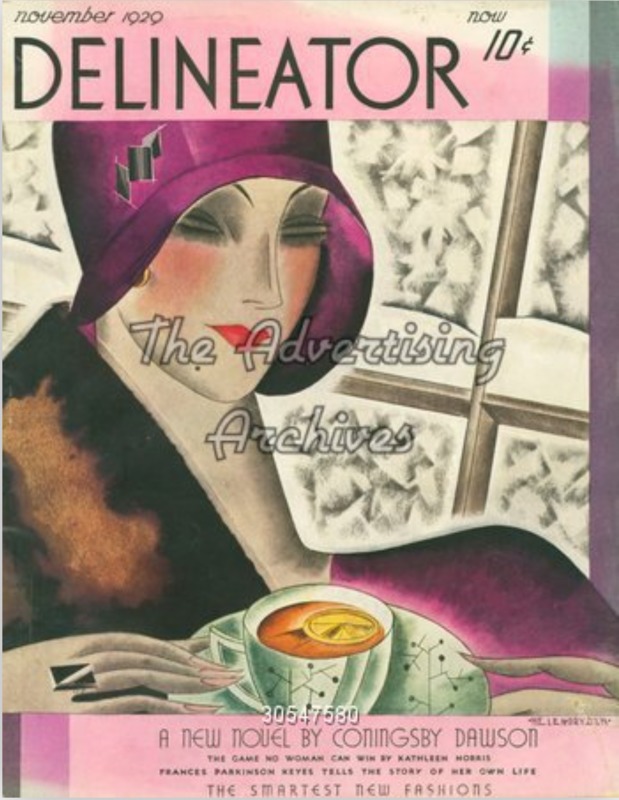

A dichotomy emerged between the views of those in urban areas and those in rural areas, which is illustrated by the two covers of the magazines The Delianator and Needlecraft. The November 1929 cover of the former features a woman wearing a vibrant magenta dress and matching hat, with her left side wrapped in what appears to be a fur shawl. Her elegant look reflects the extravagant nature of the 20s and the fact that she is drinking tea sends the message that tea is a luxury commodity. It also represents the urban desire for modernity, which is seen with the glass windows in the back, the pattern of the teacup and saucer, and the vivid colors of the woman’s dress and makeup; this all contributes to the atmosphere of sitting in a cafe in the city.

Modernity for women specifically manifested in the flapper movement: the desire for sexual liberation led women to wear shorter dresses, cut their hair, smoke, and drink to show that they could participate in activities that were deemed “masculine” (Reeves 86). The woman’s outfit is an appeal to this image, as the style of dress is much different than the conservative outfits of the past decades. The fact that the woman is drinking tea then points to the creators of the image wanting to associate it with urban life and modernity. Given the lengthy history of tea one could come to think it is an old-fashioned beverage, but the beverage becomes modernized once a modern woman is shown enjoying it.

The date of the image is interesting to note as this was soon after the 1929 stock market crash that led to the Great Depression. The capitalization of extravagance is still present despite the quickly declining economy, which sends the message that the status quo is being maintained. Tea, then, becomes a symbol of relaxation as the woman is contently drinking it in a state of ignorant bliss as to the state of the nation. Her facial expression of closed eyes and a smile coincides with this idea of being ignorant, as she is blind to her surroundings and is instead focused on the experience of the tea. The effect on the female consumer is that they too should be unconcerned with America’s financial situation and can continue the spending habits that they established in the years prior; there is even enough time to relax with a hot cup of tea.

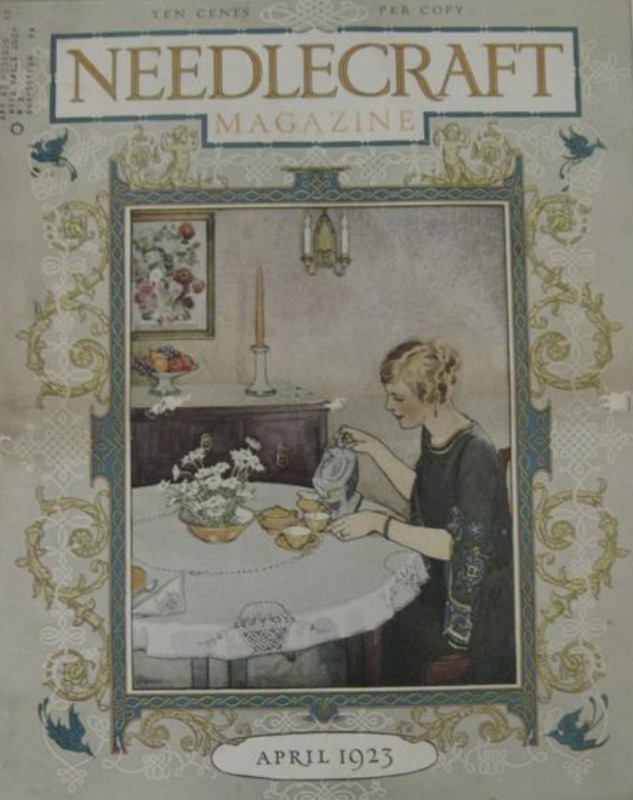

The 1923 Needlecraft cover creates a vastly different atmosphere. The woman is depicted setting three cups of tea at a nicely set table. She wears a long black dress with flowers decorating the sleeves, a similar style to the dress worn by the woman on the Record-Herald cover. The setting feels very homey compared to the hustle and bustle of city life, pointing to the magazine appealing more to a rural or Southern reader base. Ramamurthy’s idea of “affect” can be applied here, as the initial feelings toward the image all revolve around the home and a simple life before one acknowledges the subject or what she is doing (367). The white tablecloth with flowers in the center of the table, the bureau with the bowl of fruit, and the painting of the vase of flowers all contribute to the domestic atmosphere and try to make the viewer nostalgic for a simpler time. The function of tea here is completely contrasting that of The Delineator, as it capitalizes on the idea of tea as old-fashion rather than rejecting it.

It's unclear who the woman is serving tea for, but given the context, one can infer that she is making tea for her family. This reinforces the idea of women as the primary homemaker, and combining it with the setting promotes the message that this traditional way of living should be maintained. There is a rejection of modernity in the image, which points to it being created by or for those living in rural or Southern areas. The religious fundamentalist movement was prominent in these areas, founded on the basis that the Bible is inherently true and infallible (Reeves 93). It rejected all things modern and believed in traditional values, which for women meant adhering to the norms believed to be outlined in the Bible. There is no direct reference to religion in the image, but the dress of the woman and the overall atmosphere fits the description of what a Southern fundamentalist would say “the home” should look like: traditional.

The woman’s actions and dress are uncontroversial and passive unlike that of The Delineator, painting a picture of the types of women who read each magazine. The function of tea in Needlecraft is to be served by a woman to her family as a means to show her love and devotion. This relates to Parkin’s idea that “food is love,” as the woman is shown to be smiling as she prepares the tea to show that she, and the female viewers, enjoy the act. The very title of the magazine contributes to this idea, as needlework is a traditionally feminized activity. Using tea as the central image in a female magazine subconsciously causes the viewer to associate tea with femininity, once again reinforcing it as a primarily female beverage.