A World of Men's Gossip

The coffeehouse crafted a reputation for gossip despite this being an incredibly feminine attribute during 18th century England. This trait goes hand in hand with the fact that women were mostly absent from them. It is clear that men did not want women in the coffeehouses. Men rallied against the idea of a woman in the space because they often "saw her presence as a threat to moral order, arguing that her seductive charms were a threat to lead coffee drinkers into vice" (Ellis 2004, 110). This idea is not hard to consider because the men inside the coffeehouses were entirely intent on retaining the intellectual function of the institution. This can be seen firstly by the collapse of the notion that alcohol must be present in these spaces. It's only logical, then, that women would also not be necessary, seen only as a distraction. This would lead to a regression of the role of women as they were much less common here than during the age of taverns.

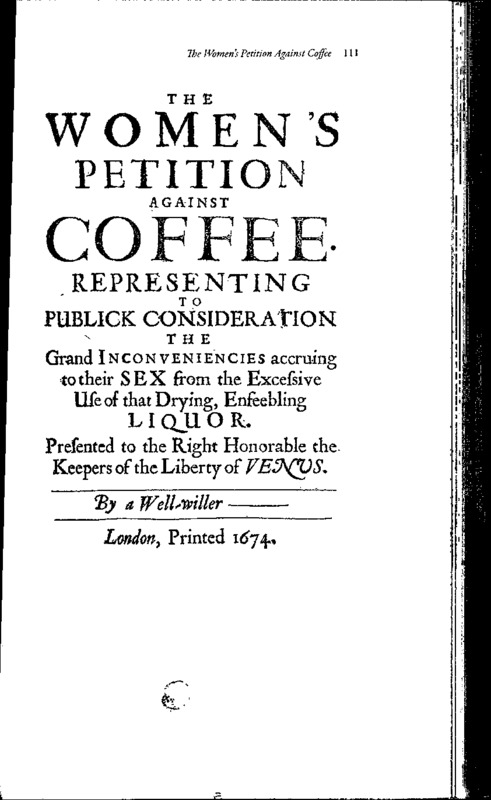

This primary source dated in 1674 dealt with the rise of the coffeehouse and the social norms it brought along to British society. It is a satirical piece written by an anonymous writer about how the Londonian women were upset that coffeehouses rendered the men effeminate. The piece makes fun of men for losing their masculinity in their newfound fixation on coffeehouses. Author Markman Ellis put the content of the text in simpler terms “The satire is directed against the cultural reformation that coffeehouses were understood to have introduced in London society: the men who congregate in the coffee-house are associated with the supposedly feminine attributes of talking and gossiping” (Ellis, 2006, 109). In the document, the unnamed women say that the men of the coffeehouse “out-babble an equal number of women at a Gossiping, talking all at once and running from point to point… insensibly and… swiftly.” Ellis notes that the theory of coffee extinguishing sexual desire and producing sterility was a concept first introduced by German and French scholars in the early 17th century. One can posit that the traditionally masculine beverage of alcohol being replaced by a drink for intellectuals and one that produced a “gossip culture” was responsible for the rumors and satire about coffee feminizing men. This gossip culture was also responsible for the newfound fixation on clothing and fashion of men in London. "Foppery, then, was the result of men importing female politeness into the masculine public sphere" (Cowan 2005, 230). These factors allow us to better understand the position taken by the women in the pamphlet.

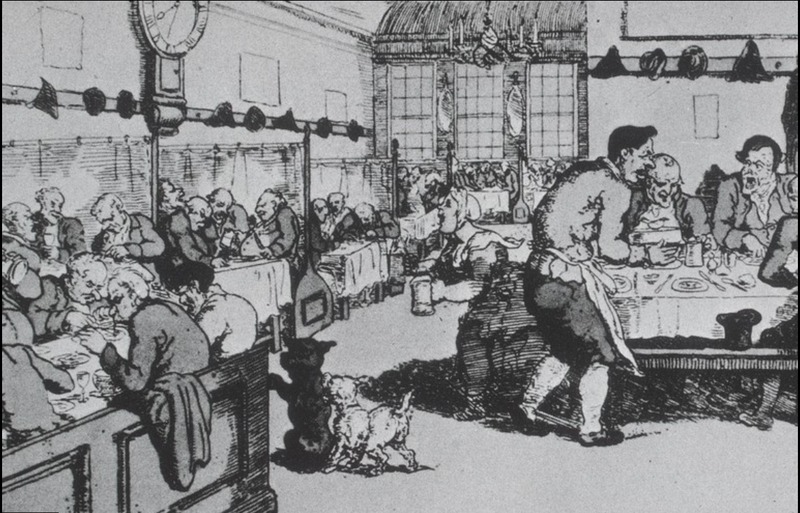

Despite this being a satirical piece, one question to consider is whether the exclusion of women from the coffeehouse scene prompted genuine angst among the female populace of London. During the Elizabethan era, where taverns reigned supreme, women had equal access to them. A 1599 description of London’s tavern life was recorded in the journal of Thomas Platter the Younger. When speaking about taverns he said “What is particularly curious is that the women as well as the men, in fact more often that they, will frequent the taverns or alehouses for enjoyment. They count it a great honour to be taken there and given wine with sugar to drink” (Picard, 228). Comparatively, the exclusivity of the coffeehouse as a men’s space is affirmed by contemporary accounts. Images of coffeehouses from the time period feature tables full of men with women absent from the picture. While some sources point out that there were no definitive laws barring women from entering a coffeehouse, it is clear that it was by no means socially acceptable for a woman of class to be seen in one. “A few isolated references exist to the presence of women in coffee rooms, but only to suggest they were prostitutes” (Ellis, 2004, 67). The fact that the only women who were accepted into coffeehouses were prostitutes speaks volumes about men’s attitudes towards women during this time. Men became so engrossed in coffeehouse culture that they neglected their wives at home and felt a patronizing sense of superiority in their supposed intellectualism by promoting the idea that women were not capable of being men’s equals in the coffeehouse setting. London women of the 18th century may have felt their status had regressed in society and felt nostalgic for the days when men acted like a gentleman towards them as their prime concern instead of being focused on political gossip in the coffeehouse.

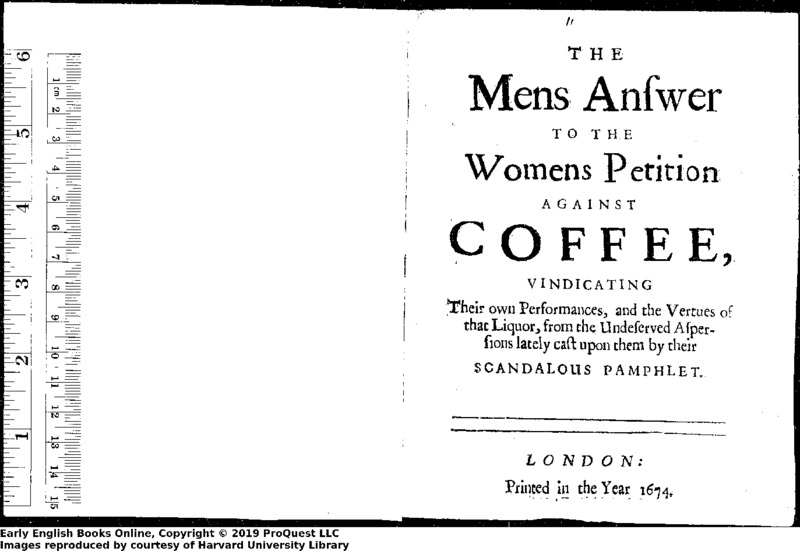

The Mens Answer to the Womens Petition Against Coffee was a defense of the coffeehouse and its effects on men. It was also anonymously written and a piece of satire. The men call the women's pamphlet "scandalous." They respond by citing the ungrateful attitude of women, and defend coffee as a beneficial asset to men. Despite the satirical nature of the text, its attitude serves as an overexaggeration of the way Londonian men were attracted to the beverage. The author describes coffee as “That harmeless and healing Liquour, which Indulgent Providence first sent amongst us… to make us Sober and Merry.” The beverage is enshrined as a heavenly commodity in this description. This is in stark contrast to the description of coffee in the Women's Petition in which they referred to it as "that drying, enfeebling liquor." The women naming coffee a liquor is significant because it illustrates their disdain for the beverage and the inability to separate it from the troubling effects of liquor despite coffee not containing any alcohol. In his defense of coffee, the author also points to the positive contributions of the coffeehouse to the lives of men. “Dear Hearts, the Coffee house is the Citizens Academy, where he learns more Wit than ever his Grannum taught him, the Young-Gallants… the News-mongers exchange… and the Wise mans Recreation.” The author touts the beverage for its ability to encourage men to learn information and be more involved in the politics of the day. He goes on to say that it is coffee that keeps men sober and free from the adverse associations of alcohol which occurred at higher rates when men spent their time at establishments other than coffeehouses. In this argument the coffeehouse is defended for its ability to spread news and information, its sobering effect on the minds of men, and its value as a place of learning and education.

This image is undated but is described by its source as circa late eighteenth century. The image has similar features to the coffeehouses already examined, yet this image has an emphasis on the gossip of the establishment. Rows upon rows of men seated discussing things are the most remarkable feature of the image. These were often political topics. The ability of the coffeehouse to spur political movements was so controversial that King Charles II tried to suppress them. A proclamation, published in The London Gazette, was made in 1676 which ordered all coffeehouses to cease functioning. Perhaps the King saw the potential for coffeehouses to be dangerous early on in their development and wanted to reduce the political damage they could cause. The proclamation was caused by the government mistrusting the people. "Identifying coffee-houses as the pre-eminent location of 'speaking evil' of the government, the proclamation urged those that heard such discourses to report them to Privy Councillors or Justices of the Peace within twenty four hours" (Ellis 2004, 88). The government also had spies which were sent to the coffeehouses to gather information. It accused the coffeehouses of practicing libel. The government was angry because it had the opinion that the coffeehouses allowed for "the foulest imputations to be laid upon the government' and that 'people generally believed that those houses had a charter of privilege to speak what they would, without being in danger to be called into question" (Cowan 2004, 36). The people viewed the government's attempt to control their speech as overreaching and most coffeehouses did not heed the initial proclamation or the subsequent proclamations that followed. It became readily apparent that the people would not listen and the government was incapable of shutting down every coffeehouse and every speech violation. "The result was a public outcry, for coffeehouses had by this time become central to social, commercial, and political life in London... not even the king could halt the march of coffee" (Standage, 145). The issue was soon put to rest and the coffeehouses were allowed to continue business as usual, but the example illustrates the powerful value of the coffeehouse in the way it affected political thought.