Indian Tea Advertisements from before Independence

In the mid-late 19th century, British born entrepreneur Thomas Lipton expanded his tea company ‘Lipton’s Tea’ into the global market. Chinese tea was popular at this time, but trying to infiltrate the Chinese market in anyway led to extreme consequences, with - as D'Antonio describes - Chinese ‘authorities promis[ing] that anyone who was caught [stealing] … seeds, plants, or even expertise related to tea would have his or her head chopped off.’ (D'Antonio, 103) Lipton eventually established his own tea plantations in India and Ceylon and recognized the benefits of marketing tea in a British owned country. Many other tea companies ‘played on the fact that [their product] came from lands where the Union Jack proudly flew.’ (D'Antonio, 112) Lipton focused on advertising to his target consumers (Britons in Britain and in India) ‘happy people with vaguely Indian or Sinhalese features working on plantations [as it] conjured a European’s idea of a tropical paradise.’ In order to maintain this link of his product with comfort and luxury, ‘he called his plantations “gardens”.' (D'Antonio, 112) Hence, Lipton’s Tea is a key example of a company using the role Britain played as the imperial ruler of India as a marketing technique. One cannot dispute that the Lipton’s Tea advertisements below directly reflected the nature of this colonial rule in India, prior to its independence.

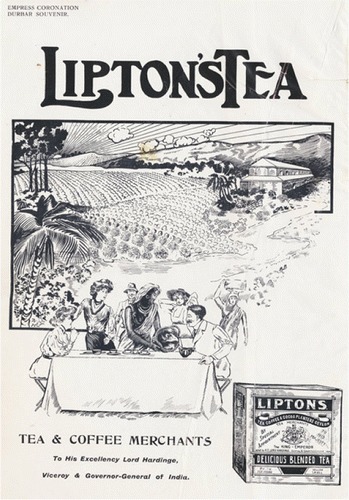

This advertisement, 'India Express' was published in a 1911 newspaper and was ‘largely aimed at resident Britishers and the Anglophone elite who aspired to their lifestyle.’(Lutgendorf, 13) It shows several white individuals who appear to be wealthy, according to the elaborte dress that they wear, being served tea by a dark skinned woman. Behind these individuals is a tranquil looking field and factory building. The overall tone of this advertisement is cordial, showing the laboring dark skinned woman to be happily serving the white individuals, and there is no indication that the field or factory in the image is in fact a tea plantation which would have been full of Indian workers. As such, the advertisement ‘celebrate[s] tea as a natural product of a colonized and tamed ‘jungle’, raised in geometrically arrayed and manicured ‘gardens.’' (Lutgendorf, 13) It is an important decision on behalf of the producer of this advertisement – Lipton’s Tea – to have erased any reference to labor from this image. The image of the factory itself ‘merely hint[s] at the complex and increasingly mechanized intermediary process involved in actual tea manufacture’ (Lutgendorf, 13) and the labor of the native people who did it.

The statement at the bottom of the advertisement reads ‘Tea & Coffee Merchants, To His Excellency Lord Hardinge, Viceroy & Governor General of India.’ This statement explicitly places this primary source within the context of British colonial rule of India as Lord Hardinge was an elite British statesman, and the position of Viceroy and Governor General are exclusive to Britain’s imperial hierarchy. Arguably this source was produced by Lipton’s Tea to assert British dominance in India, specifically through their rule of the tea trade. One must consider that there was a deliberate reason to dedicate this advertisement to the British Imperial ‘ruler’ of India of the time, alongside an image of a dark-skinned woman serving a group of white people. The message of this source is very clear, the British were the ruling force in India at this time (1911) and, through the heavily controlled ‘message’ of tea production, serving and consumption, indicates that the dark-skinned natives are subservient to the white skinned British.

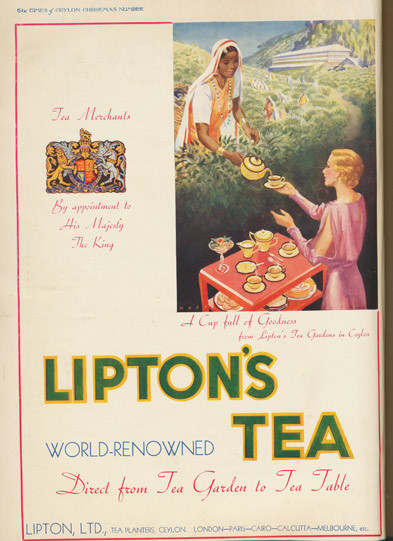

This primary source, ‘Lipton’s Tea: World Renowned, Direct from Tea Garden to Tea Table,’ is an advertisement for Lipton’s Tea, published in the Times of Ceylon Christmas Number in 1935. The advertisement depicts the racialized nature of tea production and serving in the subcontinent at this time. In the image, a woman with dark skin in a tea planting field reaches over to serve a white woman tea. Much like the previous advertisement, the image is cordial and shows the women happily interacting with one another. The dark skin color of the woman serving the tea identifies her as a native of Ceylon (modern day Sri Lanka). Ceylon was a British colony at the South Eastern tip of India. In the background of the image are more Indian women picking tea in the field, which differs from the erasure of these individuals in the previous source. By showing this dynamic of a dark-skinned woman serving a white woman, the tea advertisement furthers the nature of British colonial rule in the Indian subcontinent, namely that the white British people were superior to the native dark-skinned people. This is shown through the role that the dark-skinned woman plays in serving the white woman, and the dark-skinned women laboring in the field.

This source was produced in a Ceylon newspaper which was published in the English language and aimed to support the mercantile interest of Great Britain. As tea was a huge part of Britain’s production, manufacturing and trade in South Asia – specifically India – promoting the sale of tea in this newspaper is clearly a way of furthering British mercantile control in that region of the world. Furthermore, the racialized image presented in the advertisement also reinforces the nature of British colonial control to the source’s audience – English speaking people in Ceylon – by showing the native dark-skinned people to be subservient to white people. This depicts the exact way in which Britain maintained control in South Asia.

This primary source, ‘Lipton’s Tea: the Connoisseur’s Choice,’ was produced prior to Indian Independence, but significantly closer to it than the previous sources were. This source dates at around 1930-1940. The closer this source is to the time of Independence is evident from the imagery used in the advertisement because the role of the individual has been removed entirely. The tea pot appears to pour itself as it fills three cups of tea. As a result, this advertisement does not speak to the racialized nature of tea advertisement and its presentation of racial hierarchy which existed in Britain’s control of India. This is therefore telling of how, as the Indian Independence movement grew stronger, the British – as represented through the British tea company Lipton’s Tea – became more conscious of how they were portraying Indian people in their advertisements.

Despite moving away from the racialized nature of tea production and service, this advertisement is still a reflection of British control in India because of its deliberate assertion of the role of the British monarchy. The Royal British seal is placed boldly at the top of this advertisement, surrounded by text that reads ‘Tea Merchants, By Appointment to His Majesty the King Emperor.’ The use of the noun ‘emperor’ very explicitly places this advertisement within the context of British colonial rule in India. Despite removing the individual from the image, and therefore not making an explicit comment on race as the previous sources do, this sources still makes it clear that India is under the rule of the British Empire. This source is a somewhat passive assertion of this control, but an assertion, nonetheless.