Conclusion

In her analysis of popular women’s magazine, Claudia in the 1960’s and 1970’s, Isabella Cosse asserts that despite the fact that Claudia extended the role of the woman from the 1950’s stereotypical housewife by including things like quizzes on the quality of a marriage, it still enforced the stereotype of beauty as blonde, white, young and thin. Paula Bontempo’s analysis of Para Ti in the 1920’s and 1930’s makes the same assertion - Para Ti prescribed the same standard of feminine beauty: white, fashionable by US standards and thin (153).

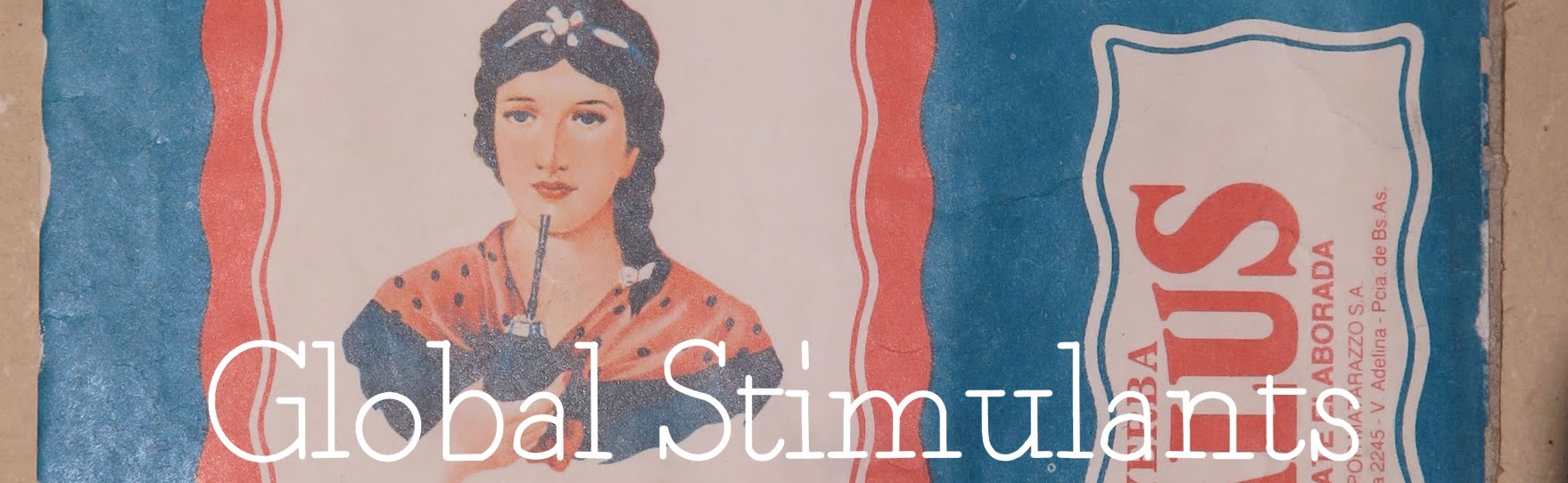

Therefore, this analysis of Yerba Mate advertisements in the 1950’s merely fits in with the larger scheme of gender roles and beauty standards in Argentina during the 20th century. However, the 50’s are particularly compelling because they were the period during which women were targeted as main consumers in the nuclear family for the first time (Parkin 14). But, in targeting women yerba mate companies simply continue the existing narrative surrounding what makes an ideal women. Their portrayals of white, young, fashionable, upper class women fits into the themes that women’s magazines push.

Yerba mate is traditionally a communal drink, consumed in large groups and passed around. It builds a sense of trust and companionship. However, in these advertisements the women pictured are undeniably alone or just about to serve their husbands. Perhaps this is a testament to the fact that the women in these advertisements is fake. She is an ideal built by corporations and advertisers to try to sell a product to other women. She cannot be a part of this communal experience if she doesn’t exist.