Nobleza Gaucha Advertisements

Nobleza Gaucha is a product of Molinos, Argentina's largest branded food company ("Company Overview"). The company sells a variety of products, including yerba mate, through a variety of different brands, like Nobleza Gaucha. Molinos was founded in 1902 and has been selling branded products ever since ("Company Overview"). They sell rice, pasta and a variety of other foods under brands like Luchetti and Gallo ("Our Brands"). Nobleza Gaucha is now one of their smaller brands and they currently have four different yerba mates on the market ("Company Overview"). Their advertisements in the 1950's for their other products were not unlike their advertisements for Nobleza Gaucha. Several advertisements for their olive oil brand, Cocinero, show attractive stylish white women cooking with the oil (“Cocinero”). Therefore, the Nobleza Gaucha advertisements were not isolated, but rather part of a larger trend within the company and within advertising as a whole.

The first advertisement highlighted here was placed in a 1950’s issue of Vosotras, a popular women’s magazine. The woman in the advertisement is wearing clothing that looks like clothing that upper middle class women in the US were wearing during this period. This is because during the Cold War, the US government promoted capitalist consumption within Argentina, including consumption of fashion (Pite 122). The idealized 1950’s housewife of the United States became an ideal in Argentina as well (122). Therefore, it is no surprise that the woman in this ad is white with blonde hair, green eyes and gold jewelry. Because of her clear wealth due to her clothing and jewelry, it is safe to assume that the intended audience for the advertisement is other upper middle class women or lower class women who might want to appear like this woman. The fact that she is white has colonial implications, as it shows that whiteness is considered by the advertisers to be a mark of beauty (Milanesio 104). Natalia Milanesio, in her research on 1950’s Argentine advertising, uses the term the “female visual cliche” to describe the typical woman in advertisements: fair skinned, big sparkling eyes, thick eyelashes, a wide, white smile and flowing hair (104). This ad plays into this cliche and this idealized standard for beauty. Also, the man in the advertisement is holding the mate and he does not appear to be as white nor as young, therefore this standard was more consistently applied to women.

The first advertisement highlighted here was placed in a 1950’s issue of Vosotras, a popular women’s magazine. The woman in the advertisement is wearing clothing that looks like clothing that upper middle class women in the US were wearing during this period. This is because during the Cold War, the US government promoted capitalist consumption within Argentina, including consumption of fashion (Pite 122). The idealized 1950’s housewife of the United States became an ideal in Argentina as well (122). Therefore, it is no surprise that the woman in this ad is white with blonde hair, green eyes and gold jewelry. Because of her clear wealth due to her clothing and jewelry, it is safe to assume that the intended audience for the advertisement is other upper middle class women or lower class women who might want to appear like this woman. The fact that she is white has colonial implications, as it shows that whiteness is considered by the advertisers to be a mark of beauty (Milanesio 104). Natalia Milanesio, in her research on 1950’s Argentine advertising, uses the term the “female visual cliche” to describe the typical woman in advertisements: fair skinned, big sparkling eyes, thick eyelashes, a wide, white smile and flowing hair (104). This ad plays into this cliche and this idealized standard for beauty. Also, the man in the advertisement is holding the mate and he does not appear to be as white nor as young, therefore this standard was more consistently applied to women.

The text in the ad is also illuminating; it promotes satisfying your husband by making him yerba mate. It mentions the husband’s “gesture of satisfaction” as an indicator of the quality of the yerba mate. Therefore the ad also confirms gender roles that already exist in the patriarchal society because it places value on the husband’s satisfaction rather than the wife’s satisfaction even though she is the one who prepared it. The “modern” woman during this time period was valued for her domestic work and women were encouraged to learn how to cook and clean efficiently (Pite 124). Therefore, the housewife in the 1950’s struggled with the juxtaposition between being the primary consumers in their household and the pressure to become efficient in domestic tasks. This advertisement was also printed in another women’s magazine, Chabela, which I found on Pinterest, which means it was widely circulated in different women’s magazines.

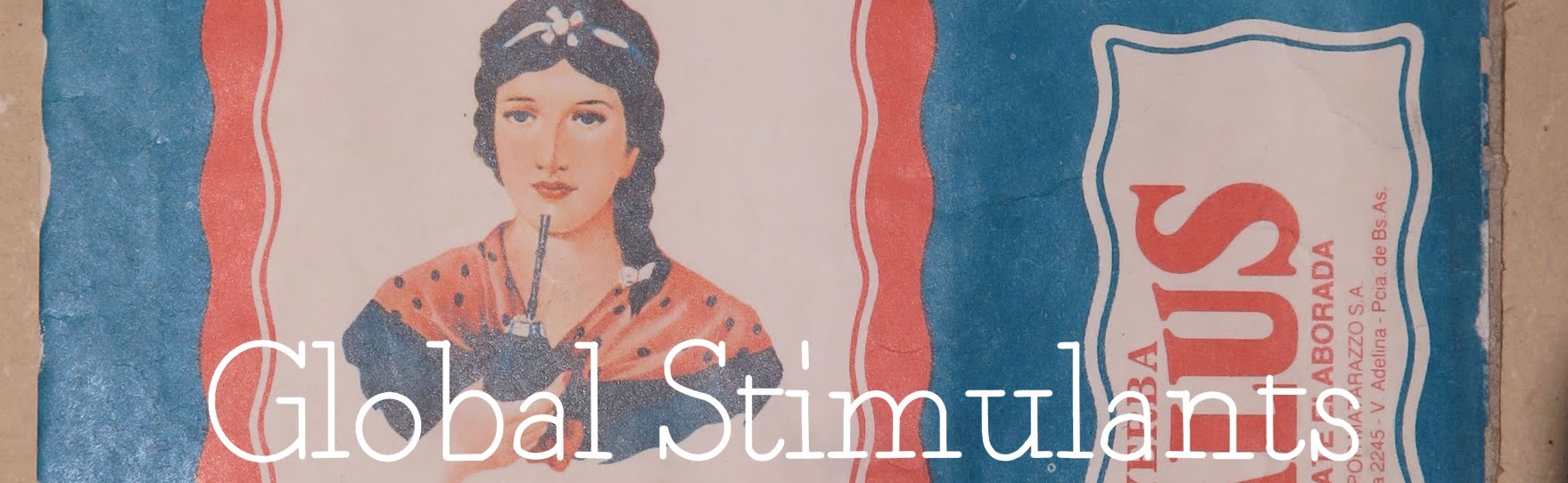

The second advertisement keeps with the thematic trends of the first. This is another advertisement from the 1950’s from a magazine. The top of the advertisement says “because we are both active we need the stimulating rest provided by Nobleza Gaucha.” The quote is attributed to a woman named Hebe B. de Andreasen, who is presumably the woman featured in the advertisement. Hebe is a white woman holding a mate, dressed in fashionable clothing from the time period. Her name is also a European name. She also has earrings and a ring. This shows that she is likely upper middle class, and that the ad is aimed towards upper middle class women or lower class women who want to seem higher class.

In her analysis of the Argentine magazine Claudia in the late 1950’s and the 1960’s, Isabella Cosse asserts that the women depicted in advertisements of women’s magazines were different than advertisements elsewhere because they “showed a young adult woman with a thin body and European features who was different than lower class women, but still clearly did not belong to the most elite classes” (Cosse). This depiction of middle and upper middle class women made the yerba mate seem attainable and desirable. This class distinction, Cosse argues, is how advertisers targeted “modern” women. In addition, there is a large chunk of text at the top that describes the modern woman, but still makes it clear that despite her modernity and her activity outside of the home, this woman is in charge of domestic tasks. This is evident in the fact that the man pictured is carrying a briefcase and is entering the door, presumably coming from work. The woman seems to have been in the home already, presumably attending to her domestic duties. This is the crux of the “modern” 1950’s woman: a woman who is able to attend to her domestic duties while still having a life outside of the home (Cosse).

One key similarity within both ads is the text underneath the company logo. In the earlier advertisement the text talks about the quality of the yerba mate and says “it is rich, frothy and aromatic. It yields many servings before running out.” The text under the later logo says “the yerba that always fills one more mate.” Although the syntax is different, the overall meaning is the same - if you buy this yerba mate you will get the best value for your money. This fits in with the context of Argentina during this time, as the economy fell into deep crisis twice during the 1950’s; therefore despite the fact that the specific years of the advertisements are unknown, it is safe to guess that the economy would have been unstable when they were published (Pite 140). Because it was the responsibility of the housewife to provide for her family, no matter the circumstance, it makes sense that a yerba mate brand would appeal to their desire to get the best value for their money.

Another similarity is that both ads portray men. This connects to Kathleen Parkin’s concept that U.S. advertisements for an audience of women will often portray men in order to emphasize that women are “subservient to men and should cater to their needs” (Parkin 9). In the Argentine context, both Nobleza Gaucha ads insinuate that the man’s satisfaction is of utmost importance. The fact that Nobleza Gaucha ads portray men is a marked difference from the Yerba Mate Aguila advertisements in the next section.