Aguila Advertisements and Nationalism from 1900 to the 1930s

Prior to the turn of the century, colonial powers like Britain maintained a looming presence in Latin America through their neocolonial investments (Chasteen, 216). Still in the Belle Epoque era, Argentines, or at least the elites in cities, embraced the foreign presence by altering their dress to mirror that typical of Europeans. By the beginning of the 1900s, however, European influence in the region was starting to wane as the imperialist US began to insert itself in its neighbors’ affairs (Chasteen, 218). In 1905, President Theodore Roosevelt added a corollary to the Monroe Doctrine which “made the US Marines a sort of hemispheric police force to prevent European military intervention in Latin America” (Chasteen, 221).

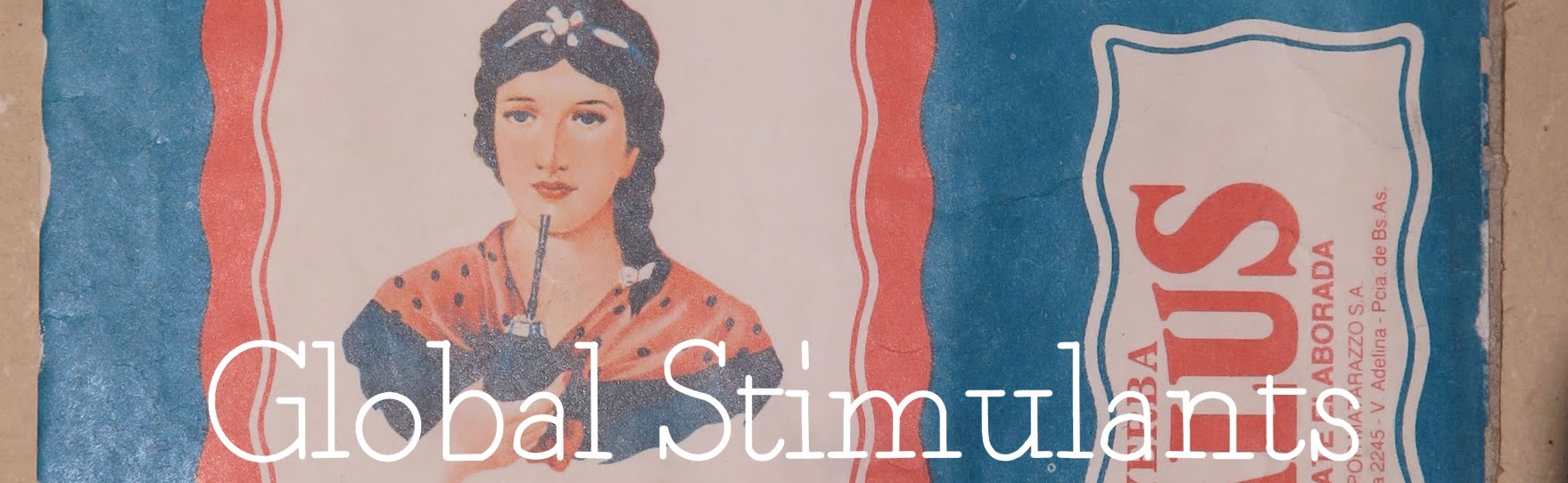

Around this time, Aguila Chocolate created and distributed the advertisement to the left. It is an illustration of a man rowing a boat. The flag on the boat reads “Grand Prize of Honor” in a shade of blue similar to the actual flag of Argentina. Under that text, it continues “universal exhibition of Saint Louis. (EE. UU) 1904.” This is particularly interesting because it marks a feat accomplished in the US at a time when the US appeared to have been dominating the region. Furthermore, the bottom third of the image reads, “Aguila chocolate with milk” with the words that the man rowing the boat is saying to himself beneath. He says “Run, little boat of mine, run fast, «Aguila» chocolate is already waiting for us. And in Buenos Aires, there is not any chocolate that compares to this one.” Although the Argentine man is not proclaiming international superiority of Aguila chocolate, he is at the very least, deeming Aguila to be the national chocolate of choice while celebrating a victory abroad. One interpretation of this advertisement is that it displays the need for foreign validation to make a product or brand legitimate, but as the century continued, Aguila encouraged Argentine nationalism in their advertisements by marketing themselves as the best of the best chocolate brands.

In the 1930s, Argentina was closing out its era of neocolonialism and entering a stage of “energized nationalist movements throughout Latin America” (Chasteen, 249). This decade also marked a watershed moment in Argentine history as international trade waned and import-substitution industrialization (ISI) boomed (Chasteen, 249). The populist leaders that rose in the following decade (the 1940s) used ISI to legitimize their nationalist pride because an increase in “industrialization meant moving out of the neocolonial shadow and controlling their own national destiny” (Chasteen, 250).

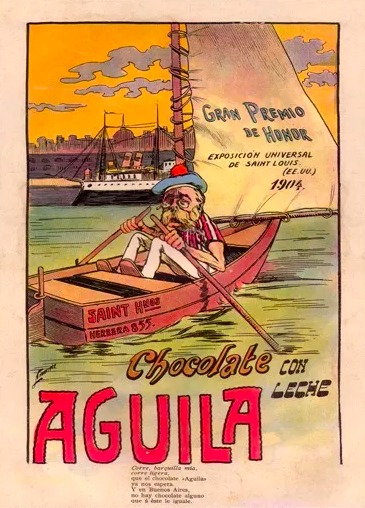

Within this context, Aguila Chocolate created the advertisement to the right which targeted the Argentine public. The Revista Aconcagua [Aconcagua Magazine] published the advertisement circa 1930. The center of the image contains what appears to be a box or tin, given its reflective illusion, of chocolate, with instructions as to how to prepare the drink. Although the box itself does not indicate how the company wanted to market its product as a nationalistic good, the surrounding text does. The text in the advertisement translates to “Aguila’s chocolate with milk is unanimously recognized as very superior to any similar European [product].” This statement, though not particularly verifiable, is clearly comparing the Argentine product to European chocolate. With this, Aguila is establishing a push past neocolonialism and the Belle Epoque as their chocolate surpasses the quality of that of the people who Argentines once believed to be setting the standards in all aspects of life. Through this image, the company also creates a direct yet subtle linkage between its name and the name of the republic. The words “AGUILA” and “ARGENTINA” are capitalized bubble letters and filled in with shades of blue that resemble the two horizontal blue bars on the flag of Argentina.

This advertisement exemplifies Aguila’s effort to establish their brand as a national product at a point in time when nationalist discussions were gaining a foothold. The branding of their chocolate as proudly Argentine chocolate served as a call to the people of Argentina to be nationalistic [domestic] consumers within their industrializing nation. It is also interesting to note “Montevideo y Asuncion” printed in the bottom right corner. These cities are the capitals of Uruguay and Paraguay respectively. It is possible that this advertisement circulated around the South American region in an effort to bolster regional solidarity and regional consumption and trade based on a mutual disdain for Europe. That disdain may have been the product of a shared colonial past with Spain.

In the same vein, the 1930 Aguila advertisement to the left is also concerned with the company’s national greatness vis-à-vis Europe. Firstly, Aguila appeals to the masses of Argentine people by showcasing the price range for the different “new types” chocolate for purchase. These new types of chocolate bars vary in size and amount from the original, smallest bar of chocolate. Highlighting the price differences between amounts of chocolate allows Aguila to show the public that they could get what appears to be significantly more chocolate for a not significantly higher price. The chocolate itself, Aguila states, has achieved yet “Another new triumph at Seville’s Ibero-American Exposition.” More precisely, “Aguila chocolate bars obtained the highest distinction awarded by the jury: Grand Prize.” Once again, it may seem like the company is seeking foreign approval of their chocolate, but that point of view is somewhat contested by the illustration toward the middle left of the image. Layered on top of what appears to be the Giralda Spire Bell Tower in Seville, are the Argentine and Spanish coat of arms with their respective flag color blocks behind them. Most importantly, Aguila layered the Argentine coat of arms on top of the Spanish one, and the Argentine flag color blocks over the Spanish. However minimal this detail may be, it connotes a subtle air of superiority and dominance. Having two Argentine layers over two Spanish layers makes it evident that this was an intentional decision made by the company.

Aguila chose to present Argentina on top in order to foster nationalist sentiment to ultimately achieve their goal of increased chocolate consumption. Based on the marketing toward the general public, it is clear that they were the target demographic needed to achieve the desired increase in chocolate consumption.

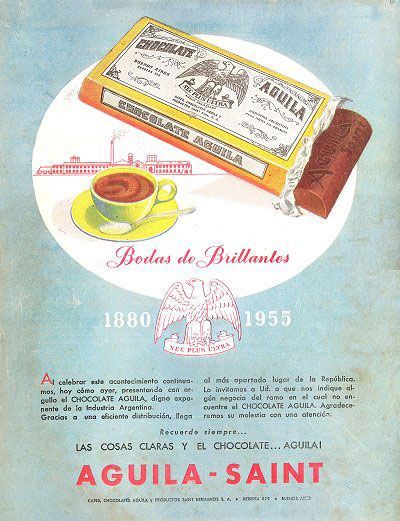

In another celebration of achievements, the advertisement to the right from 1955 honors the 75th anniversary of Aguila Chocolate. In the mid-twentieth century, populist leaders Juan and Eva Perón led Argentina and appealed greatly to the industrial working class (Chasteen, 271).

The primary text in the middle of the advertisement produced during the Perónist rule reads, “Wedding of Diamonds.” Diamonds are traditional gifts for 75th wedding anniversaries (Hallmark Corporate). The image itself contains a drawing of a chocolate bar, box, drink and factory in the center of the advertisement, but it is primarily in the text where the message relating to nationalism lies. Aguila states that “In celebrating this accomplishment we continue, today as yesterday, to proudly present Aguila Chocolate, worthy exponent of the Argentine industry.” In a display of nationalist pride in productive capability, Aguila has chosen to speak to their contribution as a national producer as well as illustrate a site of their production through the image of a factory toward the center of the advertisement. Doing so enables the brand to present itself as an important factor in an element of national identity and dignity. Establishing Aguila and Argentina as capable producers further separates Argentina from its colonial past, asserting its economic independence.

These examples exhibit a trend in advertising that aimed to generate national sentiment based on larger trends in Latin America that reflected desires to move past extractive colonial histories. The brand did this in an attempt to drive national chocolate consumption. Based on the marketing toward the general public, it is clear that they were the intended demographic needed to achieve the desired increase in chocolate consumption.