Chocolate Over Time: Trends and Forward Progress

In the mid-twentieth century, advertisements portrayed women in relation to those who defined their roles as girlfriend, wife, and mother. Food advertising and chocolate in particular emphasized romance and family structure, relating food to love and emphasizing a woman’s need to be in a relationship with a man and provide food for her family. In a world where women were taught that food is equal to love, providing healthy snacks for her children was paramount. As a result chocolate advertisements preyed on a mother’s desire to keep her children happy and healthy during the mid-twentieth century. By showing illustrations of smiling white children or using colorful pastels in their advertisements the advertisers clearly marketed their product for children’s consumption. The dairy lobbyists pushed for this milk chocolate and cocoa to be viewed as healthy, and so milk content was often used as a validation for the chocolate’s healthiness. The advertisements therefore provided women with an option that seemed to satisfy and enrich their children.

As time moved on, however, women’s accepted place in society changed. When self-indulgence and independence became more acceptable in women and traditional family roles became less prominent, chocolate could be marketed as a health food towards adult women for their own consumption. Gone are the pastels and smiling children, and present are the dark hues surrounding luxurious, satisfied women. Health and pleasure are now meant not only for the children, but also for women.

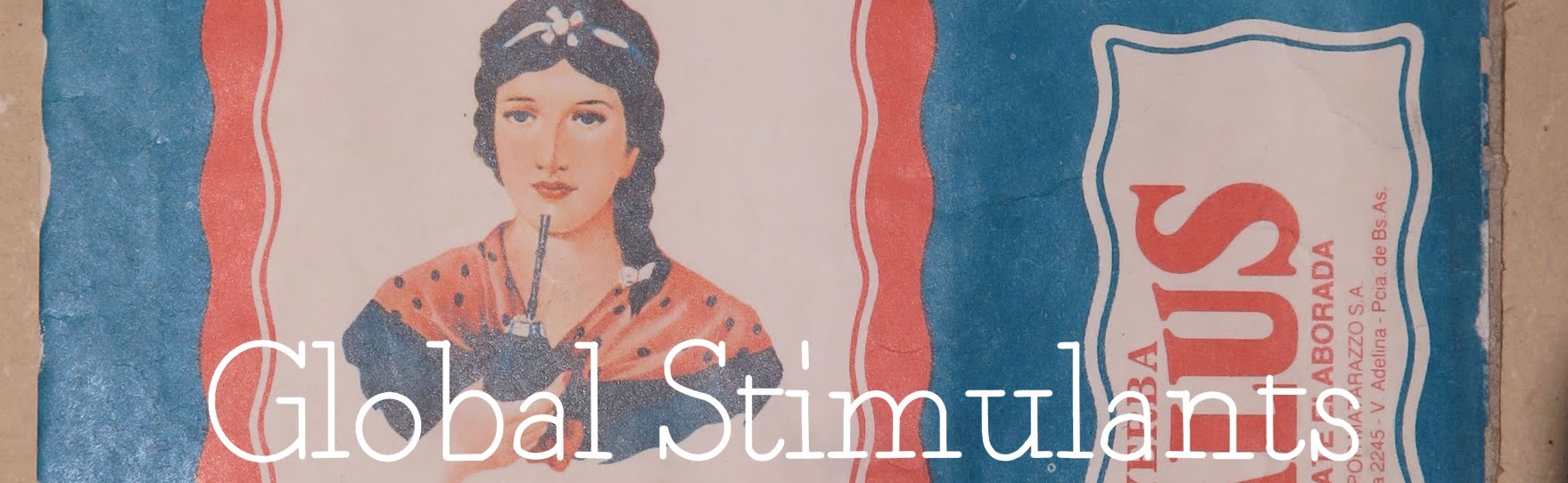

Partially due to chocolate’s reputation as an aphrodisiac and partially due to the advent of romance in advertising in general, chocolate companies also stressed romance when advertising to (and with) women. In the mid-century period, Cadbury and Whitman’s as such used younger women, in relationships with men, to link chocolate with pleasure and demonstrate that men should purchase chocolate for women, and that women should encourage these romantic gestures. In this time period, chocolate advertising seemed more about romance than sex, consistent with societal expectations and advertising trends in general. Later ads from Godiva and Cadbury, well after the women’s liberation movement began, demonstrate that, with the rise in women’s independence and individualism, women were portrayed alone in advertisements, but while they could indulge themselves and buy chocolate alone, the goal was still to be sexy and desired, as women in advertisements presented an ideal for women to strive towards.

Advertisers know that consumers are aware that they’re being tricked or convinced, and yet advertisements still work (Davis 1). While we have situated the endpoints of our exhibit well before and well after the women’s liberation movement (as well as the rise in individualist consumer culture in general) of the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, we still see women objectified, taught to act desirable, and better themselves for others. In what ways are we (women especially) falling prey to our insecurities, and buying the chocolate that will supposedly make us the healthiest and most desirable, or the foods we saw children enjoying in an ad, or still encouraging the giving of chocolate to women as a romantic gesture? Additionally, we can consider that the ideal consumer is not just an attractive, middle-class white woman, even if we have come to expect that from our ads and culture. If we remember that these are constructions of advertisers, perhaps we can be more critical as consumers and continue to improve expectations of women in society (not just in advertising).