Expansion of the Tea Plantations and Cheap Labor

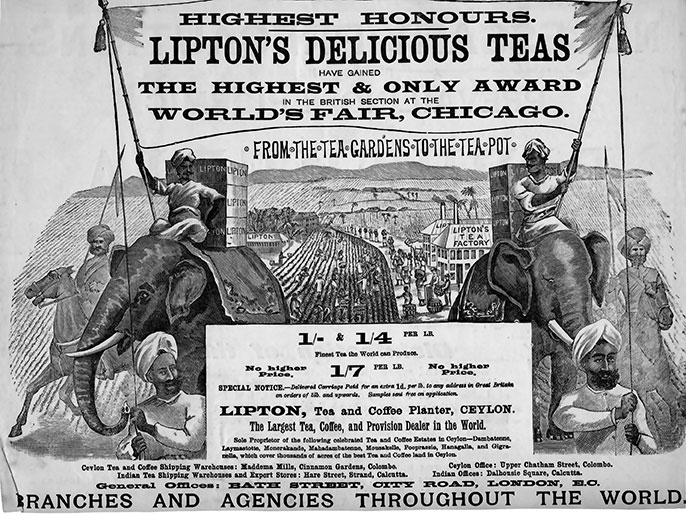

It is important to explore the implications and conditions of tea laborers in Sri Lanka and how they were depicted in advertisements used in Britain. “At the Chicago World’s fair of 1893, the East India pavilion served tea within a spectacular display of ‘oriental’ splendor. Lipton won the “highest honours” at the same exhibition and proclaimed its supremacy through a baroque set of oriental images: elephants, striding horses, turbaned natives, all heralding the “Lipton Tea Factory” in the background and the suggestion of active laboring bodies”(Chatterjee, 2012). Many advertisements from that period of time depicted foreign people and laborers as exotic, unknown and new to the Britain tea market and put crucial focus on symbolizing the tea export from Sri Lanka as a direct and newly effective way to enjoy a fresh cup of tea (Ramamurthy, 2012).

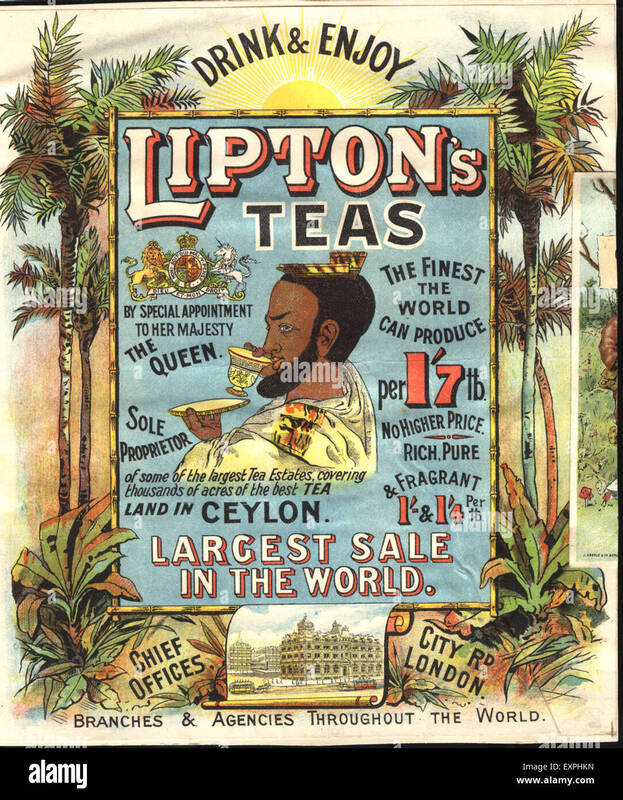

Thomas Lipton was surprised to hear how little they paid growers for the product they stocked, and astonished by the profits they earned (D’Antonio, 2010). It seems as Lipton was aware of labor exploitation within the market, but looked at it as even a bigger opportunity to expand, it was a win-win situation for both sides. Lipton’s tea advertising, which showed happy people with vaguely Indian or Sinhalese features working plantations, conjured a European idea of tropical industrial paradise. To link his product with comfort of home he called his plantations “gardens,” Lipton was written on every drawing of a factory, wagon, or crate (D’Antonio, 2010). Lipton was already buying big shipments of tea from Ceylon, surely knew the country produced a good reliable product, and he was always eager to control every link in the supply chain of any item he sold. According to Michael D’ Antonio, Lipton paid around 25,000 pounds sterling for five thousand acres tended by more than three thousand workers (D’Antonio, 2010). Sir Thomas Lipton saw an opening and did not hesitate to keep going, the exploitation of the workers in Sri Lanka was not a concern, but rather looked as a good economic opportunity for both sides.

In her analysis Anandi Ramamurthy, focuses on exploring racism and its representations as well as archiving and narrating people’s histories of resistance. In her essay she explains the growth of globalization where consumers can affect positive change by exercising the choice of opting for fair trade. Exoticism has always been present in creating an image for tea and Lipton’s first image represented an ‘exotic belle’ holding a cup, smiling demurely out at the viewer. The embracing of this image in the 1920s and beyond, however, can be seen as the representation of imperial control through a ‘softer’ gendered hierarchy that naturalized the East as female and the West as male” (Ramamurthy, 2012). Lipton’s advertisements certainly had a huge impact on how the British people imagined the so-called “East” and the world beyond, especially at the end of the 19th century. The language of colonialism in the late 19th century changed to a belief of partnership, images of the producer interacting with or acting as the consumer in the domestic space of the garden emerged repeatedly. The famous slogan “From the tea garden to the teapot” in one popular image visualized the exchange between two cultures and highlighted sharing the experience domestically. Thomas Lipton made the most out of that domestic labor in Sri Lanka and capitalized on tea sales in Britain with an implication of aggresive advertisment.