Introduction: Linking Women with Chocolate

In twenty and twenty-first century advertising, women have been consistently linked with chocolate. Whether women are purchasing their own chocolate, buying it for the family, or being gifted chocolate by men, female subjects have dominated in chocolate marketing campaigns. Early in the twentieth century, advertisements were aimed at women but with a focus on relationships, whether with men or with children and families. From the late 1940s to the present, marketing trends have reflected the change in societal expectations for women, and the “modern” woman in advertising has often been portrayed as independent or self-indulgent, as family units have become less stressed, and more women have entered the workforce. In the present day, advertisements assert that women can buy chocolate for themselves, but often as a way to better themselves to meet societal expectations. While overtly encouraging independence, advertisements still play to women’s insecurities, both manipulating women as consumers and reflecting societal trends. Within this emphasis on women as chocolate consumers, advertisers also use different themes and lenses, and here we examine two such themes over time: chocolate as a “healthy” or beneficial food, and the role of chocolate in romance and sex.

In what ways has chocolate been marketed to women as a health food, and how has this differed over time?

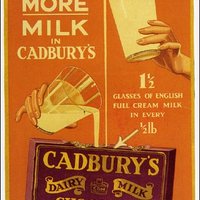

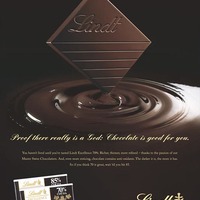

The debate over chocolate’s health effects has always been important in chocolate advertising and consumption. Because it is something that people have historically loved to eat, finding a way to view it as nutritious is a popular goal. Numerous scientific studies have looked at chocolate to find health benefits with varying results. A lack of scientific certainty, however, has not prevented chocolate companies from marketing their products as healthy. Even where chocolate is not directly advertised as a health food, the pervasive conversation surrounding the topic impacts chocolate’s consumer base. In the 1940s through 1960s milk chocolate was advertised to mothers to feed their children as a healthy snack or beverage. Some remnants of this idea are still present today, but more recently dark chocolate has taken hold as the healthy chocolate option. Dark chocolate, rather than being marketed to women to purchase for their children, is primarily marketed to women for their own consumption. The change in marketing of chocolate as a health food to women is indicative of a shift in women’s gender roles. Where women were initially seen as interested primarily in their family’s well-being, more modern gender roles allow women to have more independence and self-indulgence. This part of the exhibit analyzes the evolution of how chocolate’s supposed health benefits were advertised to women in the United States from the mid-twentieth century to the present and how this correlates with the shift in perceived societal roles of women.

How have sex and romance been used to advertise chocolate to and with women?

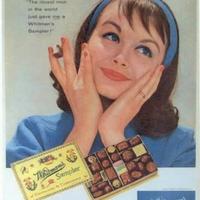

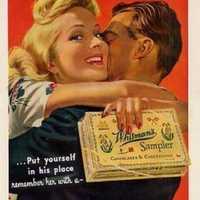

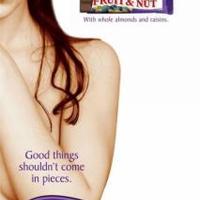

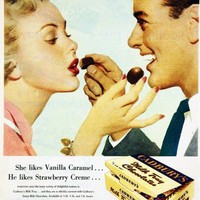

Another trend in chocolate advertising is the use of romance, eroticism, and highly sexualized imagery. This has changed over time with standards of acceptable advertising, with the most sexualized images being seen closer to the present (Sivulka 39). While many advertisements focus on more tangible or achievable goals such as health, another class of advertisements dating back to the 1920s and 1930s began to relate products to abstract concepts such as romance, virtue, wealth, and so on. Around this time period advertising attached to the concept of self-assertion and individual aspiration, especially along the lines of “buy our product and be like this person.” Advertisers also began associating eroticism and desire with products (Illouz 81-82). Additionally, chocolate has long had a reputation as an aphrodisiac, so romance is a natural advertising theme (Nutter 199). For these reasons, romantic relationships between women and men, as well as the sexualization and romanticism of women in general, are common advertising motifs. This part of the exhibit examines how romantic relationships were used to advertise in the 1940s-1960s, and how while “independent” women in advertisements were pictured without men by the 2000s, they were instead sexualized. We are concerned here with the way features of advertisements encourage women to be desirable. While these features often are the same as those encouraging men to desire women (and thus the product), we focus on ways women are targeted specifically.

In all these cases, it’s important to note that the women portrayed and targeted are almost entirely younger, middle-class, white women in the western context. This cannot be divorced from the general observations about romance, health, or sex, as the advertisers are here demonstrating who their “ideal customer” is. While some allowances must be made as these are American and British companies who do advertise to a white majority (and a few of the more modern ad campaigns have made strides to include women of color, such as Godiva), the racial implications are still strong. The health habits of white housewives for their families are assumed to be both the best and the most important to influence, and white women are the desired romantic and sexual partners. Each of these companies seeks to be popular among what they see as the “ideal” segments of society, and this was and remains largely the white middle class.