Role of Female Laborers

Women’s labor recruitment was integral to the success of tea plantations in the 19th century to the early 20th century. Recruitment strategies reflected the explicit desire for women, as they had the power to procreate a continuous labor force (Chatterjee 1995, 54). However, the way in which planters encouraged female emigration was very particular— they believed that single women who willingly came to seek work were in some way looking to escape their former lives and ties to their husbands, parents, or guardians. (Chatterjee 2001, 81). Officials did not believe this was valid rationale to join their workforce. As such, they sought to control the agency of the female in creating a formalized policy inderticting single women from joining the plantation. In the early 1920s, the Tea District Labor Association only allowed married women to be registered to work on plantations, noting that “no woman was to ‘bind herself by a labor contract if her husband or guardian would object’” (Chatterjee 2001, 82). In denying women the ability to come to the plantation unaccompanied, the administration was creating another form of worker bondage; women did not have the ability to escape their previous, potentially dangerous living situations to have the opportunity to live independently. The following images portray how the restrictive nature of women’s recruitment is represented in depictions of labor practice.

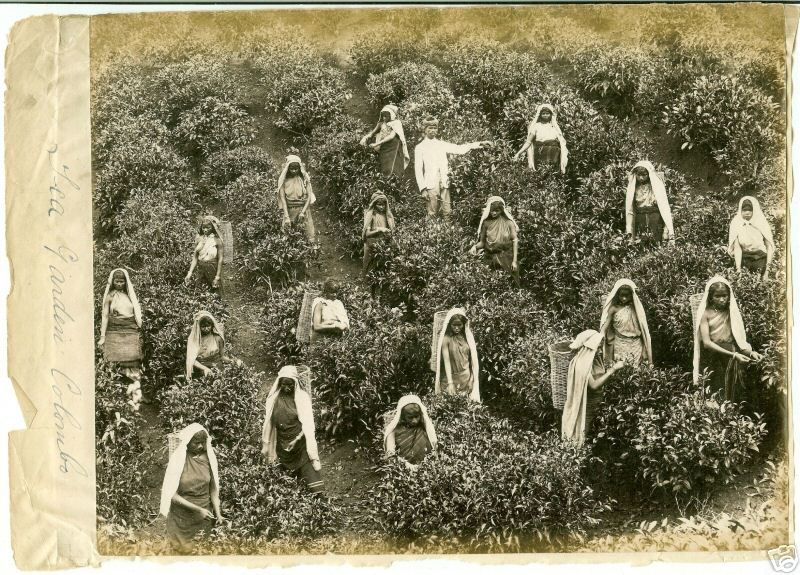

This first photo depicts tea pickers in a tea garden in Colombo, Ceylon from an album coming from the late 1880s. Though there is no context provided as to who created it and for what purpose, the image is important in depicting what the result of gendered labor recruitment looks like in practice. Chatterjee notes that women completed much of the agrarian labor, and most intense field cultivation. The administration justified this in noting that “where in certain processes such as plucking, women are handier than men” (Chatterjee 2001, 82). In this image, one can see that while the females are all working to pluck leaves from individual bushes, there is one man who stands isolated, posing by a bush. Likely, this man was hired by the colonial administration to oversee the females’ labor.

As described earlier, the labor recruitment strategies which rejected the independent woman’s admission into the plantation shows a lack of trust on behalf of the colonial administration and desire to control the agency of the woman. Similarly, this image depicts an extension of that desire to regulate the free-will of the female in depending on the male planter to keep the women’s work in-line.

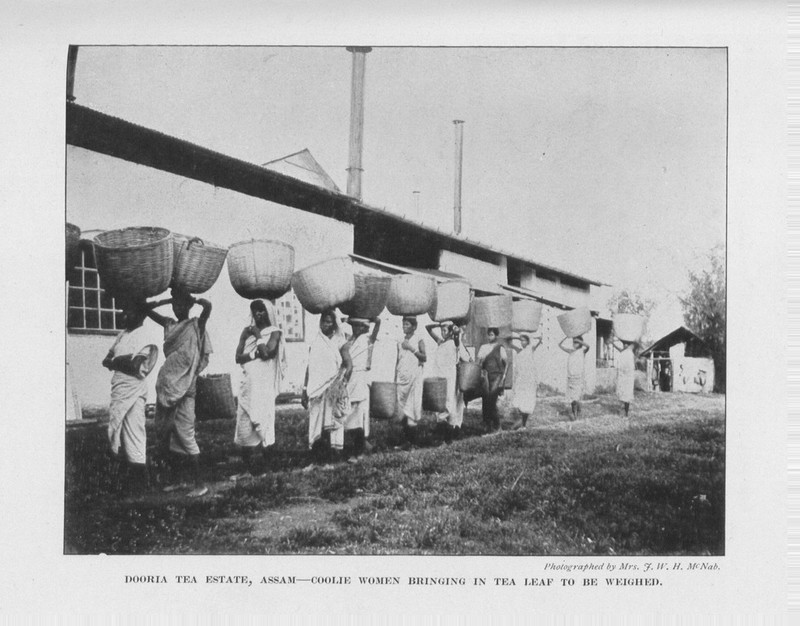

This second image is a photograph of Dooria Tea Estate in Assam from the early 1900s. According to the source, the photograph is taken by “Mrs. J.W.H. McNab,” but her identity and background are unclear. The image depicts “coolie women bringing in tea leaf to be weighed.” One can note the laborious task of the woman in carrying harvested tea on their heads. There is also noted fatigue, as several of the women wait with their arms crossed, or on their heads for additional support. Moreover, the lineup of the women mimics that of a factory line— very mechanical and systemized. Similar to the way in which the restrictive labor recruitment processes encouraged a very regimented labor force, these working women serve a strictly functional purpose. This image displays another example of the ways in which female laborers are unable to exercise any notion of freedom.