Family Recruitment

In the 1860s in northeast India, as the colonial administration began to curate its labor supply, they encouraged the strategy of “family recruitment.” Generally, in encouraging labor recruitment through the family, it provided a form of stability for the tea plantation (Chatterjee 2001, 80). When the entire family migrated to live on a tea estate, it completely disconnected them from their original home. This, in turn, ensured that the families remained as a unit, and had less reason to leave to go back to their homelands. Furthermore, when planters could virtually guarantee that families would settle permanently on the plantations, there was no longer a threat in individual workers moving elsewhere to seek employment or live with other family members (Bhowmik, 240).

From the inception of tea plantation work, there was a desire for a balanced workforce of both male and female workers. In 1863, the chief commissioner of the Assam Company made note that while the rate of men immigrating to the plantation was increasing, females only constituted 5% of total immigrants. In order to combat this issue, the Transport of Native Labor Act III of 1863 was established, in which a superintendent of emigration could “refuse embarkation passes if the new ‘batch’ contained fewer than one female to every four male laborers to ‘facilitate stabilization of the labor force, and the promotion of community life on the estates’” (Chatterjee 1995, 53). After this point, it is estimated that from 1870 to 1900, roughly 700,000-750,000 recruits came to Assam, including men, women, and children (Sharma, 1307).

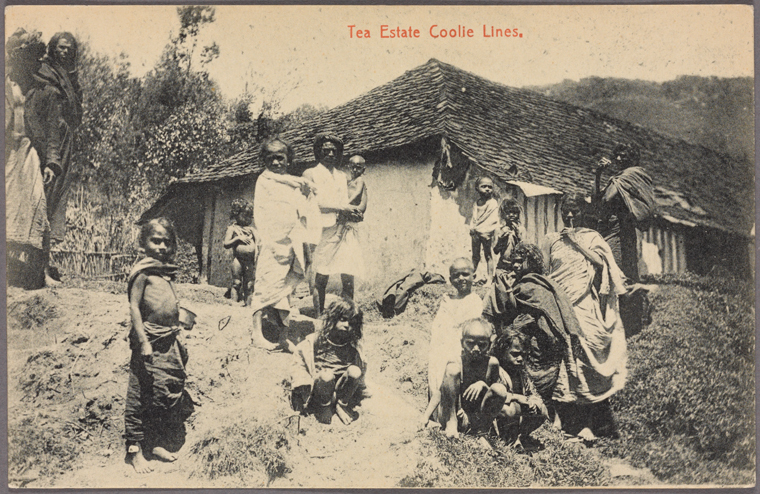

This is a still image of “coolie” laborers on a tea estate in Ceylon [Sri Lanka]. The image appears on a postcard issued in 1907, created by A.W.A. Plâté & Co., a photographer who was active in Ceylon in the late 19th/early 20th century (NYPL, “A.W.A. Plâté & Co.”). The photo is labelled “Tea Estate Coolie Lines,” with “lines” referencing the housing accommodations for families living on a tea estate. It is important to note the evidence of the family unit in this photo— consisting of both male and female workers, and their children. The colonial administration sought to control labor supply through asserting a mock “community” within a diverse labor force. They determined who would be able to work on the plantation, and how they were meant to live. By emphasizing the necessity for families to live and work together, they ensured that they maximized their labor supply, prohibiting labor coming in any disparate form.

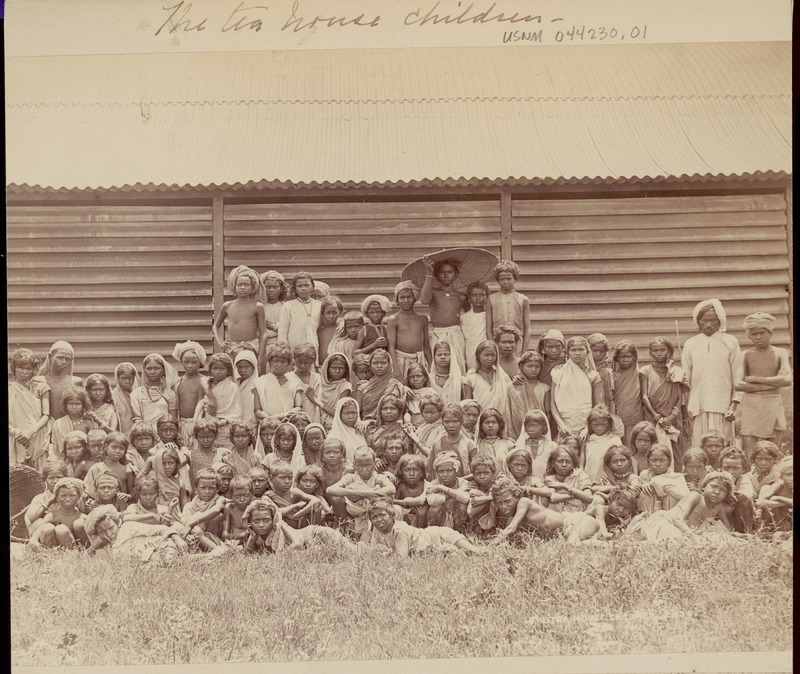

This photo depicts children outside a tea house in Assam, being labelled as “The tea house children.” The photo is undated, but its reference notes that it was most likely taken in 1903 or earlier. It is produced by Bourne and Shepherd, a commercial company which published photographs of the Indian landscape, and was sold in retail throughout India and Britain (National Portrait Gallery, “Bourne & Shepherd”). Though this image looks like it may have been staged, it is representative of the emphasis placed on the child as being a part of family recruitment policy. In fact, the great number of children present is indicative of just how important this labor group was to the functioning of the tea plantation. As noted in secondary scholarship, the colonial administration originally used the “family” as the unit for employment in the tea industry. As a result, they could officially permit employment of child labor (Bhowmik, 252). While women were completing tea plucking, children were “sent out to catch caterpillars and other insects on the tea bushes” (Chatterjee 1995, 54). In this photo, one can note the tea basket on the head of one of the children in the back, highlighting the fact that they were also participating in labor.

As such, this image depicts that more than simply living alongside their parents, these children represented a category of labor exploited by the colonial administration. Not only were they bound to plantation work as children, but they would grow up engaging in the same work and eventually become the main supply of labor of the following generation. This presented little to no opportunity for the family to escape the inherent form of worker bondage which the administration indirectly instituted.