Popularization in Japan: Eisai and Eison’s Influence

As mentioned on the last page, the gift of tea seeds and practices of Zen Buddhism made their way from China to Japan, but despite accounts of there being multiple trips of Zen Buddhist monks between China to Japan, one monk in particular is credited with these feats: Buddhist priest Eisai (Standage 132). Despite tea being a known beverage since the 6th century CE in Japan, in 1191 CE Eisai’s return from China with knowledge about the latest tea cultivation and drinking practices as well as Zen Buddhist practices transformed the country (Standage, Hohenegger). This was due to Eisai's work to immortalize these ideas by working to restore Rinzai Zen temples, creating the sect of Rinzai Zen (one of three sects of Zen Buddhism in Japan) that would be practiced by the largest school of Zen Buddhism in Japan to this day (Driem). In regards to tea, he wrote a treatise entitled Kiss Yojo-Ki highlighting the medicinal benefits of tea according to ancient Taoist principles of China (Towler, Hohenegger, Driem 2019).

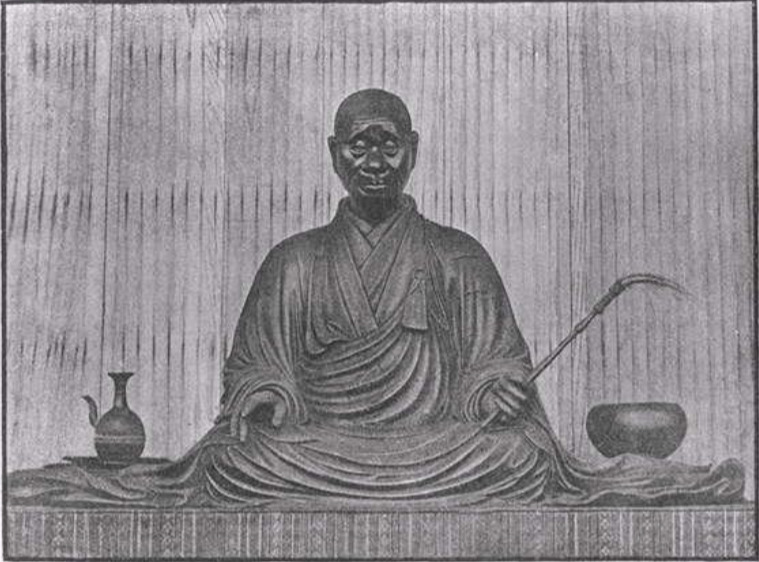

These medicinal benefits were further endorsed by Buddhist priest Eison, who is remembered as having taken tea out of the monasteries and introducing it to the common folk in Japan. He traveled across Japan teaching the practices of Buddhism to some 97,710 people and curing the poor and sick with tea (Meeks 2019). As this wooden statue of Eison by a well-known sculptor at the time named Zenshun shows, Eison is commonly portrayed with a large tea bowl beside him (right), commemorating his generous sharing of tea to the people he encountered in his travels (Int. Research Cnt. for Japanese Studies). Unlike most tea bowls of the time, the one he’s pictured with has a wider opening meant for sharing with multiple people--differing from most tea bowls of the time that were for individual use--simultaneously linking his image with tea and his generous Buddhist nature (Driem). This statue in particular, created in 1280 CE, still survives today in the Buddhist Saidaiji Temple in Nara, Japan that Eison helped to restore (Saidaiji). To this day, Eison’s practice of the "Great Tea Ceremony" remains a “popular event” at the temple, immortalizing his legacy with tea and Buddhism (“Nara Traveler’s Guide”).

While Eison brought tea to the common folk of Japan, Eisai brought it to the upper, ruling class. After being acknowledged by the sitting emperor, Go-Toba, for both his Rinzai temple restoration work and help in healing Japan’s military ruler, Minamoto Sanetomo with tea, Eisai gained warrior class patrons during this Kamakura period (1185-1333) and promoted tea for its medicinal qualities (Driem). With the adoption of tea for its medicinal properties, and the growing favoritism of the disciplining and austere Zen over the court-approved, more conservative, Tendai Buddhism amongst Japan’s warrior class, the reputation of tea and Zen became increasingly more powerful (Driem, Hohenegger). By the 14th century, tea had become widespread at all levels in Japanese society with Zen masters and tea masters often becoming one in the same (Standage 132, Hohenegger).

This photo of an illustration of Eisai is one of the most common reproductions of his image portrayed by Zekkai Chusin during the Muromachi period (1338-1573 CE) (Driem). It is presumed to be the oldest depiction of Eisai in existence, and is kept at the Ryosoku-in temple in Kyoto, Japan. The artist, Zekkai Chusin, was a Rinzai Zen monk who is known to be “one of the two greatest scholar-poet monks in the history of Zen Buddhism in Japan” (The Met). He is seated in a fashion common for Buddhism monks to be portrayed in, with his legs crossed underneath him, and his shoes removed. Despite Eisai’s legacy being strongly connected to tea, there are no allusions to tea in his portrait, and there seem to be little translations of the writing above his portrait as well.

With the contributions of the two early Zen Buddhist monks, Eisai and Eison, both early tea culture and Zen Buddhism flourished in Japan, spreading to people of all classes (Hohenegger). Without tea’s popularization in Japan, it would have been unlikely that Japan’s tea culture would have grown to be as widespread as it is today in Japan. Both scholars and material artifacts allude to these monks’ contributions, but upon further analysis the simultaneous practices of tea and Zen by both of these monks helped tea’s spirituality to spread and thrive in feudal Japan.