Early 20th Century: Agricultural and Economic Growth of Cocoa

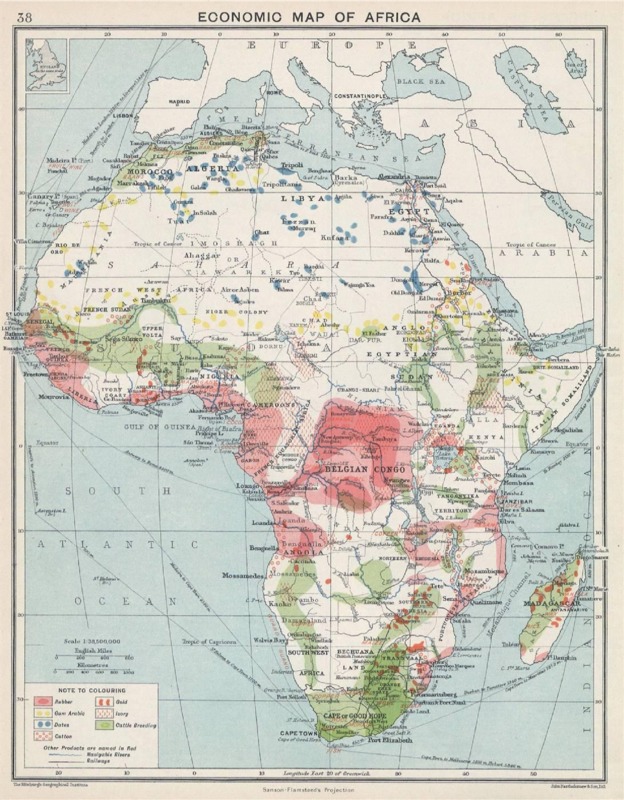

By 1900, cocoa was being perceived by farmers and economists as a legitimate commodity. This map, commissioned in 1928 by the Edinburgh Geographical Institute, highlights various commodities that were being produced in Africa for export to Europe. Additionally, this map was created during the “Scramble for Africa”, a time when several European countries were invading large regions to set up colonies and deplete the continent of natural resources. For this reason, it makes sense that the cartographer and interested economist would highlight natural African commodities like rubber, cotton and gold as opposed to foreign cocoa.

Cocoa was being produced in modern-day Ghana , Côte d’Ivoire, Nigeria, Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea and Gabon, indicated by typed red “COCOA”. This map suggests that cocoa was localized to a selective region on the coast. Cocoa was first introduced to the Ghanaian coast before British colonization, and southern farmers found it favorable to grow alongside crops like palm oil and rubber (Leiter and Harding, 122). But by 1928, the Gold Coast colony was fully operating and occupied land far to the north. Still, cocoa wasn’t being planted there. This limited land space is striking when compared to a map of South America in the same year. Here, cocoa is so widespread, encompassing the entire north and central part of the continent and occupying inner land, near rivers far from the coast.

The British were well aware of ways to grow cocoa in less tropical environments, and documented much material for workers to grow cocoa away in a book called Cocoa: All About It. There was also a significant workforce in the northern territories of the Gold Coast, many of whom were farmers (Hill, 1-19). The likely reason for cocoa’s small area of production was that the British, among other Europeans, were more concerned with natural resources and not interested in expanding cocoa production north. It’s interesting to see how even a century after cocoa was introduced to Africa, its vectors of production were limited because British officials underestimated its potential. One might also consider that the Americas had large plantations that required different types of labor and land space than West Africa, which, by 1928, had primarily small, family-owned farms (Historicus, Austin). However, Ghana produced 566,000 tons of cocoa annually by 1964, which attests to their efficiency despite land size (Leiter and Harding, 122).

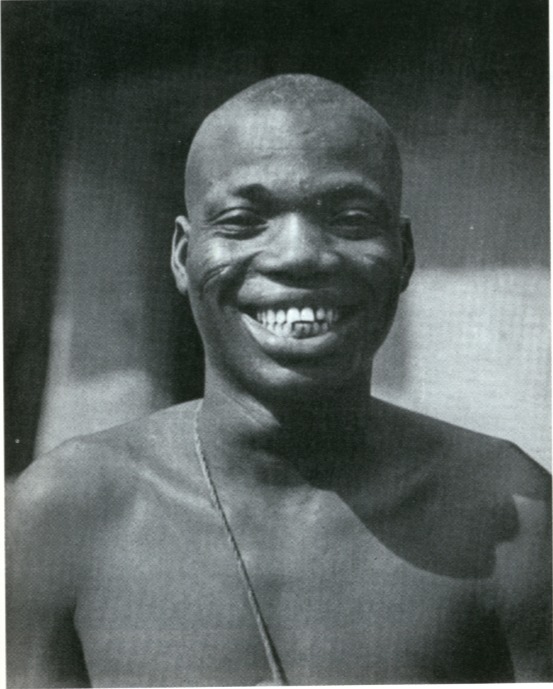

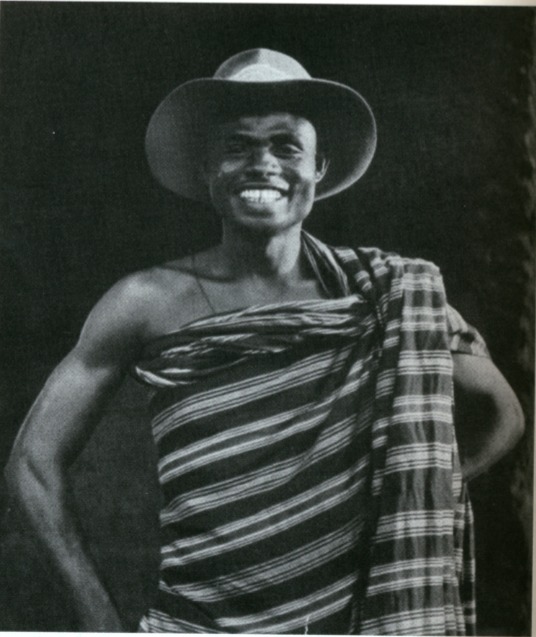

The following two photographs are profiles of a southern forest worker and a northern migrant worker, respectively. These photographs are from Labour, Land and Capital in Ghana, and were taken in 1937 by a British man as part of an economic report of the colony. Although both workers come from different labor backgrounds (small farm owner vs. migrant worker), their photos are similar. They wear similar clothing and are positioned in blurred backgrounds, suggesting they are represented as the same regardless of their origin and claim to the land. Historian Anandi Ramamurthy makes an argument about tea advertisements that also applies to this case. As a British audience, these photos “speak to [them] in complex ways urging [them] to identify with the subjects” (Ramamurthy, 368). By photographing only their faces with no farms in the background, manual labor is “romanticized as individual and purposeful” (Ramamurthy, 368). The laborers are detached from their work to make the labor seem less intense or present. This momentarily highlights individuality although the actual report stresses that cocoa was benefitting the colony as a whole. Additionally, both workers have large smiles, which Ramamurthy explains makes them complicit in their own erasure as laborers. By smiling, “‘we signal our docility and our acquiescence in our situation… in being made invisible, in our occupying no space’” (Ramamurthy, 376). Austin compliments the obedient, happy laborer argument in stating that “what colonial officials thought about labour attracted more attention than the actual workings of labour markets” (Austin, 4).

These portrayals are not representative of the labor that was occurring and generalize the very different people who are doing the labor. Despite the way the Ghanaians were treated and perceived, they made great progress from the past century (Austin, 13). After the ending of slavery in the late 1800s, both native and migrant workers “used their freedom precisely to bargain with potential employees” (Austin, 18). These farmers worked as sharecroppers, securing slightly better contracts and working conditions. This shift in agency of generally poor, illiterate farmers foreshadows a shift in agricultural and economic power Ghanaians needed to build their own economy.

As the desire to become independent grew throughout the Gold Coast, the economic and agricultural stability of cocoa farmers became a great concern for revolutionary leaders. In the following article, published by an unknown Ghanaian author in The Gold Coast Independent in 1922, farmers are viewed as indispensable, because by mobilizing the poorest members of society, all Ghanaians can “unite for self-protection and mutual benefit” and emancipate themselves from the “autocratic” British government. Additionally, the author applauds the work of farmers and the boundless opportunities of agriculture. Young men should be “encouraged seriously to think of it in preference to any other [job]”, indicating that the prestige and potential of cocoa is being recognized by others. The author shows this newspaper’s elite, English-speaking audience that enlisting the support of cocoa farmers will contribute to the larger independence effort.

This article was written after the author attended a meeting of the Cocoa Farmer’s Association. After witnessing the “earnest, forcible eloquency” with which they discussed issues of labor and agriculture, the author lays out a plan to cement cocoa as a profitable market. Most importantly, farmers needed to take control over cocoa production. Cocoa farming requires detailed attention, as beans are prone to disease and sensitive to variations in temperature and moisture (Leiter and Harding, 114). A report from British officials in the Agricultural Department in 1915 noted that the government was expanding cocoa farms through the Gold Coast much faster than farmers could care for them, overwhelming them and resulting in the spread of disease (Saunders et al, 7). Additionally, because “the meaning of quality as a criterion was far from clear”, the government took advantage of farmers by selling unfermented cocoa beans for cheap (Leiter and Harding, 125). To rectify these issues, the author suggests a formal scientific education to develop biologically sustainable methods of agriculture. Another important innovation is to begin selling fermented cocoa instead of cocoa beans, which will enable farmers to improve the quality of chocolate and raise the price in the markets. We'll see how non-fermented beans can greatly impact farmers' sales with the image of the thorn carving on the next page.

A report from British officials in the Agricultural Department in 1915 notes that “the energies of the peoples… are chiefly centered on cocoa cultivation”, which makes cocoa the perfect crop to center their economic plan (Saunders et al, 7). Also, the article notes that these farmers actively desire change. In their meeting, “the Farmers loudly demanded that the ‘Commonwealth must go!’”, highlighting their distaste for colonial rule and their potential to actually create a positive system.