Mid 20th Century: Ghanaian Innovations and the Decline of Cocoa

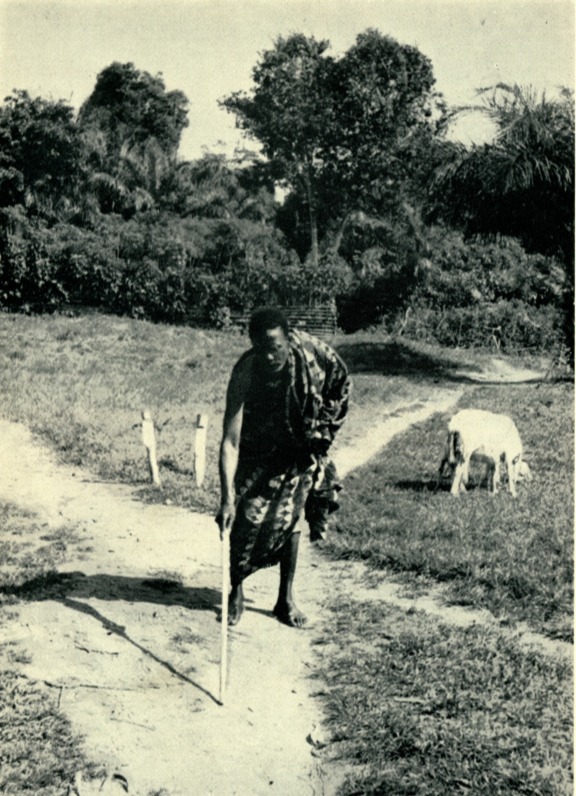

With the independence of Ghana in 1957, the government took a larger role in land ownership. This image shows a migrant cocoa farmer working on a piece of government-distributed land. It has been tapering, or unnaturally widening as crops are planted, so this farmer is applying his “instinctive knowledge of geometry” to section off the awkward piece of land (Hill, 46). This photo is shown in the context of the Ghana Ministry of Agriculture using British agricultural techniques to carve up pieces of land for farmers to cultivate cocoa. Yet, the people forcing these techniques are absent from the image, while the farmer toils away. Historian Polly Hill credits the “remarkable” efforts this migrant farmer has taken to correct the “embarrassing extent” to which the land tapers, essentially correcting the government’s attempt (Hill, 45).

In this image, the migrant farmer – who comes from the Northern region for cocoa season – is pictured alone. He works on a large plot of land with a single stick, while an animal is allowed to graze in the background. His isolation and simple materials suggest he is uneducated and not keeping proper farming techniques, which is the opposite of what Hill is trying to argue. This underlying message contributes to the misrepresentation in labor portrayals.

Ghanaian and British officials considered this type of work to be “unskilled, uninventive, neglectful, and disorganized and believed them to result in poor quality produce” (Leiter and Harding, 123). Despite the farmer’s “instinct”, the company pushed back on their methods, claiming that uneducated farmers who didn’t understand multiplication or area couldn’t properly treat the land. Hill counters this argument by attesting that “farmers neither measure, nor take interest in, the length of their strips”, which is indicated by the casual, almost instinctive nature in which the man in the image works to section off land (Hill, 44). In a tropical forest “where man is the beast of burden and the wielder only of axe, hoe and hatchet”, it is difficult to rely on foreign standards for farming, and cocoa laborers displayed a work standard that prevailed for generations (Hill, 47). The consistent dismissal of farmers’ practices is very clear here and highlights a disconnect between laborers and leadership.

Nigeria, like Ghana, was a former British colony that became independent in 1960. The image here is a thorn carving created by Nigerians between 1940-1972. Carvings like these are miniatures depicting scenes from Nigerian life, such as the transportation of cocoa from farms to markets. With similar farming systems, Nigeria was a smaller version of the Ghanaian cocoa industry, so their art – and life – is generally representative of that in Ghana. Leiter and Harding explain that “after carting their produce to market… by foot along poor roads, small holders would sell [cocoa] at the going price before making the trek home… severely limiting the profitability of cocoa production for producers” (Leiter and Harding, 124).

We can see a lot of this statement in the carving of three men moving a cart with five bags of cocoa beans. These beans have only been harvested, not fermented, so they can be sold for a cheap “going price”, which suggests farmers didn’t profit much. Like the article writes, the men are walking, barefoot, with visibly dejected looks on their faces. They are dressed in baggy clothes and two are wearing hats, which suggests they spend a lot of time in the heat. If we consider the real-life counterparts of this carving, we can visualize how hard farmers work to sell their crops and how difficult it must be to sustain a livelihood with low sales. Even if these farmers were working with Brokers [merchants], like the newspaper article suggested, there was no guarantee their hard work would pay off. Leiter and Harding note that the government should ensure proper means of transportation and adequate compensation for farmer’s crops, given how essential cocoa was to Ghana’s economy. With their failure to do so – just like the British – cocoa farmers continued to suffer from low sales into an economic depression in the 1970s (O’Malley, Leiter and Harding). Ghana yielded its spot as the highest cocoa producer in the world to Côte d’Ivoire and never gained it back.