Late 20th Century and Present Day: Cocoa's Revitalization Through Fairtrade

Modern-day cooperatives and companies are working to ensure fair treatment of laborers that goes beyond a fair-trade label and places the Ghanaian farmer in a position of power and agency over the cocoa. When this is reflected in images, historian Peter Burke explains how viewers are ‘eyewitnessing’ history based on individual’s non-verbal experiences that may not be properly depicted in text (Burke, 13-14). The following images come from collections of two cocoa companies that produce chocolate in Ghana. As seen in the image of the migrant farmer and two laborers on previous pages, sometimes images can send unintended messages or fall into inaccurate depictions of the actual labor. Here, despite the confidence in their business models for fair working conditions and pay, these images carry underlying messages that suggest Ghanaian farmers are not in control of their product.

This image comes from Divine Chocolate, a British chocolate company that works with the Kuapa Kokoo [good cocoa farmer] cooperative, based in Kumasi, Ghana. While other photographs in this collection reflect innovations by showcasing machines, women and various stages of chocolate production, this image is centralized on harvesting cocoa pods. The bright yellow pods are at the foreground of the photo, and they seem to have more of a presence than the blurry cocoa farmer in the background. This choice of perspective has the opposite effect as the rest of the collection, because the cocoa itself is given more attention, essentially power, than the farmer harvesting it, who takes up hardly any space in the photo. Without the farmer, cocoa becomes a less personal, more exoticized commodity, one that simply appears without consideration of another side of the supply chain. Burke explains how camera angle and focus, essentially “the process of distortion… is good evidence of the mental or metaphorical ‘image’ of the self or of others” (Burke, 30). This photo is the first in the collection, and it sets an impersonal tone for the rest of the images, which defeats the purpose of the collection: to highlight Ghanaian farmers’ innovation and presence in the cocoa industry.

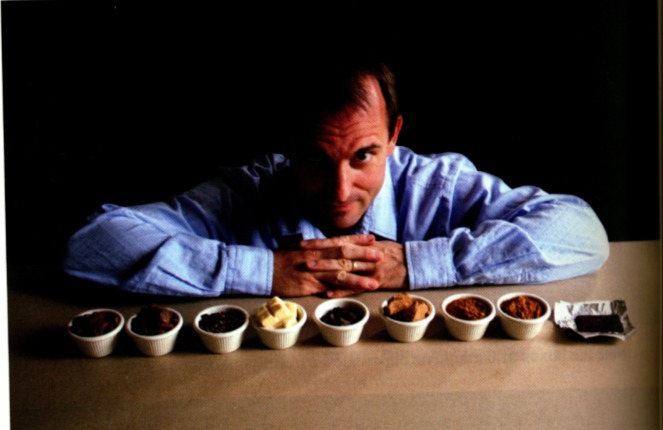

This image comes from a collection in Obroni and the Chocolate Factory, a book published by Stephen Wallace, an Obroni [foreigner, i.e. white person] who founded Omanhene chocolate company in Kumasi. The book is a 40-year account of his efforts that culminate in a riveting story of a common man who built a successful small business in a market dominated by big Western corporations (Wallace). He speaks highly of his Ghanaian house family, many of whom were invaluable to the business and continue to run basic operations today. However, this image ignores all those people and singles out Wallace. He sits in a black background, removing any visual distractions. He takes on a power pose, leaning over the row of bowls of cocoa in each stage of the chocolate-making process, which suggests he has the sole claim over every aspect of production. As Burke explains, “the postures and gestures of the sitters and the accessories or objects located in their vicinity… are often loaded with symbolic meaning” (Burke, 25). Here, Wallace’s encroaching posture and the shadow over part of his face and the table reveal a foreboding and controlling tone on his end that completely erases the efforts of Ghanaian workers that he acknowledges as invaluable. This is the last image in the book, cementing Wallace’s power as a white American over Ghanaian farmers, attributing the innovation and success to only him.

Burke explains how “we ignore at our peril the variety of images, artists, uses of images and attitudes to images” that show discrepancies in representation (Burke, 16). Representation is vital, because as Ramamurthy explains, many consumers are “encouraged to pay the premium for fair trade” if they believe the workers on the other side of the supply chain are being fairly treated (Ramamurthy, 377). The fact that these images were published by the companies that produced them shows the viewer that they care about laborers and production methods on a personal level, as outlined in their mission statements and company histories. However, the messages of the images above indicate that they still hold biases of superiority and have a way to go to offer positive representations of cocoa labor.