Labor Depictions: Romanticization of Production and Export

Capturing Brazil

During the 19th Century, various Brazilian and European artists showed interest in capturing the essence of Brazil’s landscapes, cities, and people, initially through paintings and drawings. Photography was used in the mid-late 1800’s and in 1861, Victor Frond became the first to internationally publish images of Brazil with Brazil Pittoresco [Picturesque Brazil] (Segala & Garchet). His colorized works portray scenery, fazendas, impressive buildings and landscapes. There are many portrayals of laborers on fazendas, similar to other depictions from the late 19th-century (Frond). Other significant photographers of the time included Marc Ferrez, Guilherme Gaensly, and Augusto Stahl. One of the main themes we gathered from analyzing these images was the romanticization and glorification of labor, leading to the erasure of the reality of brutal labor conditions and the identities of the laborers themselves.

Marc Ferrez

Though his father was French, photographer Marc Ferrez was born in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. As a landscape and industrial photographer, he took pictures both outside and in his studio, also focusing on plantation labor. He is best known for his landscape photography, but images of Brazilian slaves working in fields were also consumed in foreign exhibitions in the United States and Europe. Our analysis featured many of his works.

The scholar and researcher who revitalized and resurfaced Ferrez’s story and work was actually his grandson, Gilberto Ferrez. It is important to note that this familial connection creates a database that depicts Ferrez’s images from a certain perspective. Even though he was known for his landscape photography, one can imagine slaves becoming part of the landscape as they were a vital part of the economy and constantly expected to work. As seen in this exhibit, they become part of those landscape scenes and production sites that Ferrez heavily captured. As discussed by historian Mariana de Aguiar Ferreira Muaze, Ferrez’s imagery - including those portrayed in this exhibit - is invasive yet far away and removed, and depicted the slave labor in an almost romanticized, civilized, and subdued manner (Muaze). Because of Ferrez’s extensive documentation of slave labor and the emphasis that was put on his work, many of the images in this collection are Ferrez’s work.

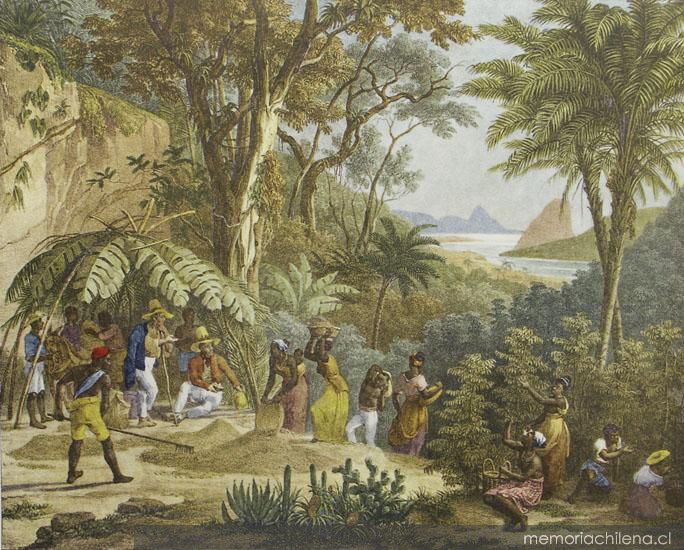

This “lamina” painting was created by Juan Mauricio Rugendas in 1821. In depicts African laborers, most of whom are women, picking and spreading coffee beans in the forest. To the left, it appears that lighter-skinned people are watching the laborers from the shade of palm leaves as they are tended to by darker-skinned men.

This is a more rural depiction of the cultivation of coffee in the 19th century, which serves as a contrast to later depictions of more industrialized plantation farming methods that appear later. Though this obra (artwork) was found in a Chilean archive, it was created by a German artist who, like Marc Ferrez, toured the Americas and captured what he saw through imagery. He toured Brazil and other places that had a large indigenous and African slave population that was still a significant aspect of the labor force at the time (Stein).

This image appears to have been artistically created using realistic colors and beautiful scenery in the background, meaning it is not just a descriptive depiction but also an art piece. The workers, who are more than likely slaves, are portrayed placidly at work in their various roles in a way that romanticizes the brutal labor conditions that were actually present (Stein). By glorifying their role in this way, Rugendas and other artists create an idyllic and normalized representation of slave labor, when the reality was that the work was exploitative and physically demanding (Muaze). This, in turn, contributes to the erasure of them as individuals and as humans. Their purpose in this context is solely to contribute labor to help Brazil’s economy.

The origins of this source also highlight the notion that European artists had significant control of the image of slavery as well as who got to showcase those images when they were initially produced. The existence of this and similar imagery, especially the volume of slave labor imagery, suggests that there was some market or demand from them as well.

This porcelain plate has been painted with a scene depicting the loading process of coffee beans from local carts to the ship. Though the plate does not have a specific date, the type of ship and use of horse-drawn carriages for transportation suggest that it was painted prior to the 1895 “Embarque de cafe para a Europe” photograph (below) and before slavery was abolished.

The emphasis of this image is on the ship and distant land. This alludes to Brazil’s broadened horizons which came as a result of the 19th-century export booms (Baranov). There is a good deal of human labor happening in the foreground of the image. The laborers carrying coffee bags from the cart to the ship, however, are not the intended focus of the image. They appear as if they were parts of a larger and more complicated machine involved in the transportation of coffee. They have become part of the scenery, rather than the subject of the illustration.

This title is translated to “Coffee Shipment.” Though almost a third to half of the illustration includes a form of labor, the creator of this piece chose to place emphasis on the transportation from Brazil rather than any of the labor required to get the beans to said shipment. By failing to acknowledge the place of the laborers in the transportation process, this source contributes to the erasure of slave laborers’ identities in the iconographies of the 19th century.

The Martha and Erico Stickel Collection was created by a Brazilian couple, but it would be interesting to learn more about who purchased items such as this plate and whether it was Brazilan consumers (middle- and upper-class, presumably), or if it was exported to Europe or the United States. In addition to analyzing the marginalized portrayal of laborers in this painting that contrasts with the impressive and large ship, we can also learn about the significance of the intended purchasers of items such as this plate, and what it means to own a commodity that depicts slave laborers working on production of another commodity.

This image was captured in Santos, a major Brazilian port, by Marc Ferrez in 1895. He often photographed ships and was named “photographer of the Royal Navy” by Emperor Pedro II (Tenebaum). The image portrays the loading of coffee beans onto a ship that is bound for the European market. It displays an aspect of human labor that was linked to the industrial capabilities of Brazil and its presence on the world economic stage. This image is similar to the “Santos. Embarque de Cafe” plate painting (above), which does not have a date but seems to have been created slightly earlier based on the type of ship. The ship in this photograph looks more technologically advanced than the ship in the plate depiction. Both represent Brazil’s industrial and economic capacity and emphasize the ship rather than the laborers involved in the export process.

The individuals carrying the coffee bags appear to be men in plain clothing, similar to the depictions in other photographs as well as paintings. Because slavery was abolished in Brazil in 1888, seven years prior to this photograph being taken, it is unclear whether these men are slaves or ‘free’ laborers. It is also possible that some of the subjects are immigrants, a category of laborers that grew significantly after the 1888 legislation (Rabelo Versiani). Though not slaves, they appear to be overseen by a man onboard the ship who wears a brimmed white hat and a more formal shirt, like the outfits seen in pre-abolition illustrations and photographs. This shows that although slavery had been replaced with wage labor, remnants of the working conditions lingered. Though there are a few individuals in the forefront of the image and onboard the ship, the individuals who are actually working are not the primary focus. Rather, they are a part of the ‘machine’ involved in producing and transporting coffee for export.

These images were both captured by Marc Ferrez in the late 19th-century and depict a large group of laborers on mountainside coffee fazendas. They are raking the cherries, a part of the drying process that precedes bagging and transporting. This process is laborious, time-consuming, and involves a significant contribution of human labor (Stein). Though the 1890 image pictured to the right was captured after the abolition of slavery (Rabelo Versiani), it is very similar to slave-era fazenda images, such as the 1882 photograph pictured to the left. In both depictions, the workers appear to have dark skin and wear plain clothes. They are working diligently while lighter-skinned men in nicer clothes gaze directly at the camera. According to historian Mariana de Aguiar Ferreira Muaze, this phenomenon was typical in 19th-century images of Brazilian coffee farms such as those captured by Marc Ferrez. In her examples and in the images pictured above, the majority of workers are focused on the task at hand and “pretend that they have been caught in the act of their work” (Muaze, 18). By depicting the laborers in this way, the physical challenge and violence involved in the work itself is erased, along with the identities of the slaves and ‘free’ laborers who are portrayed.